ISSN: 0213-2052 - eISSN: 2530-4100

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/shha31300

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF FREEDIVING: A FOUNDATIONAL STUDY

Arqueología del buceo en apnea: un estudio fundacional

Emilio RODRÍGUEZ-ÁLVAREZ

Designated Campus Colleague

School of Anthropology, University of Arizona

emilio.rodriguez.alvarez@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0696-0371

Fecha de recepción: 6-5-2023Fecha de aceptación: 18-9-2023

ABSTRACT: This study explores the presence of divers in the archaeological records of the Mediterranean basin. Direct evidence of diving is scarce, which has contributed to hiding their presence in the scholarship. Although references to divers have been preserved in the literary record, no attempts have been made to correlate these statements with the archaeological record. By applying a new theoretical framework that emphasizes ethnography and experimental archaeology, this study is able to link several misidentified artifacts to the work of divers, a first step towards a better understanding of the important role they played in the economy of their communities.

Keywords: Freediving; Preindustrial Divers; Sponges; Urinatores; Diving Physiology; Ethnoarchaeology; Underwater Warfare.

RESUMEN: Este estudio explora la presencia de buceadores en los registros arqueológicos de la cuenca mediterránea. Las pruebas directas del buceo son escasas, lo que ha contribuido a ocultar su presencia en los estudios académicos. Aunque se han conservado referencias a los buceadores en el registro literario, no se ha intentado relacionar estas informaciones con el registro arqueológico. Aplicando un nuevo marco teórico que hace hincapié en la etnografía y la arqueología experimental, este estudio consigue vincular varios artefactos mal identificados con el trabajo de los buceadores, un primer paso hacia una mejor comprensión del importante papel que desempeñaron en la economía de sus comunidades.

Palabras clave: Apnea; Buceadores Preindustriales; Esponjas; Urinatores; Fisiología del Buceo; Etnoarqueología; Guerra Submarina.

1. INTRODUCTION

Freediving is an activity that seems to offer no possibilities for the archaeologists due to the apparently succinct and perishable nature of its artifacts, especially when compared to other crafts analyzed in the archaeological record, such as pottery, farming, or metalworking. This work aims to demonstrate that it is possible to develop an archaeological study of divers in the Mediterranean basin in antiquity and that the evidence to succeed in such a task is hidden in plain sight. Mediterranean archaeology, especially the one devoted to the Greek and Roman cultures, has found in divers none of their usual topics of interest, relegating their important socio-economic contributions to footnotes on translations of Oppian, Pliny, and studies related to the use and exploitation of the sea.

2. DIVERS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN: THE STATE OF THE KNOWLEDGE

Despite the importance of ethnographic records on communities of divers in the Mediterranean basin, especially regarding the harvesting of sponges1, interest on the topic has been extremely limited. The only systematic study of divers in antiquity is a historiographic paper entitled Scyllias: Diving in Antiquity, by Frank Frost2. In this study, the author compiled all literary evidence from Graeco-Roman sources that made reference to divers. The name Skyllias refers to a diver from Skyone, in the Chalcidic peninsula, who, after being conscripted by the Persians to serve in Xerxes’ invading army in 480 BCE, defected to the Greeks, but not before triggering the destruction of the Persian fleet at Cape Artemission. Fifty years after the events, the historian Herodotos followed the official Athenian explanation, claiming that Boreas destroyed the fleet in response to their prayers3. However, there is a second tradition, in which Skyllias dove in the middle of the storm and cut off the ropes of the anchors of the Persian fleet, which crashed against the cliffs or got lost in the open sea. This feat was honored by an elegiac poem by Apollonides4.

A parallel tradition recorded by Pausanias in the 2nd c. CE mentions the existence of two statues at Delphi honoring Skyllias and his daughter Hydna, who would have also participated in the attack5. According to Klein6, the Esquiline Venus would be a marble copy of the original bronze statue erected at Delphi, taken by Nero to Rome as one of the many works of art he spoiled from Greece, but extensive literature on the topic has presented other identifications such as the goddess Venus herself or an idealized Cleopatra VII-Isis7. Pliny the Elder also mentions a painting by Androbios representing this dive, now lost8. The reference to Hydna is especially interesting since women are not generally mentioned in Greek literary tradition, but her presence as a diver in our sources will become very significant later in this study. Herodotos, however, does not mention Hydna, and the historian is not precisely the main supporter of the diving skills of Skyllias, which he puts in question.9

Frost’s research provides some of the earliest references in the Greek language to the use of divers to collect shellfish10 and concludes that there were three main areas of application of diving skills: commercial fishing (including both sponges and mollusks, as well as fishes, octopuses and squids), salvage, and war11. Frost also prevents the risk of believing some of the comments of these “non-divers” “landsmen” (sic.) ancient authors who “try to sell their books to the largest possible audience” by including non-realistic narratives of the work of divers. Paradoxically, Frost falls into the same problem when he dismisses some of the practices described by ancient authors as pure speculation. When describing a passage in Oppian’s Halieutica, one of the major sources for understanding divers in the ancient Mediterranean, he dismisses the possibility of capturing sargos (Diplodus sargus) by hand12 as a bravado told by divers to scholars, annoying them with their questions (sic.)13. However, traditional freediving communities and modern spearfishers can easily illustrate how several species can be captured by hand (see Figures 5 and 6). Frost’s compilation of ancient authors was a detailed and meritorious work that has served as an index for any research on the history of freediving14. The main problem is that there is no material correlation to this philological study; due to the perishable nature of the divers’ equipment, written sources appear to be the only evidence we would ever have.

Underwater warfare seems to have attracted the interest of ancient writers more than any other activity, and several records of combat divers performing similar feats to those of Hydna and Skyllias have been preserved in the literary record. It is far from the scope of this work to cover their actions in detail, but some brief comments are worth consideration. It seems that their main purpose of divers in combat was to make undercover attacks on the ships’ anchors and drift them ashore. During the siege of Byzantium (193-195 BCE) by Septimius Severus, divers were able to nail chains to the hulls of the ships and cut their anchors, allowing the besieged troops to drag them ashore15. During the battle of the Syracusan harbor (415-413 BCE), Athenians recruited divers to remove the underwater counter-measurements deployed by the besieged Syracusans. Tyrian divers were used to dismantle the siege works laid by Alexander the Great during the siege of Tyre in 332 BCE16, while Spartans relied on divers to supply the contingent besieged by the Athenians on the island of Sphacteria (425 BCE)17. Divers were used in a similar role during the siege of Mutina when the town was besieged by Anthony in 43 BCE18.

Divers were also employed in salvage operations. The earliest direct reference mentions the use of divers by King Perseus to recover an underwater treasure offshore of Pella in 168 BCE19. Roman urinatores were ubiquitous in coastal areas, and some inscriptions recovered in the vicinity of Portus (CIL VI.1872; 29700; 29702; 40638) indicate they were organized in a guild. The prevalence of auricular exostosis in some of these communities may be related, at least partially, to the extensive use of divers in the salvaging of cargo lost at the sea, a phenomenon especially common when transferring goods from the ship to the piers20. In the Digest21 and the Rhodian Sea-Law22, the right of divers when retrieving goods from shipwrecks is regulated: a third of the value from dives up to eight fathoms (c.15 m) and half the value if from fifteen fathoms (c.27 m), due to the risk of the dive.

Diving has been analyzed not only as an economic activity but also as a metaphor for life, death, and divine epiphany. Any search for artifacts related to diving will lead, almost exclusively, to the figure of a young Etruscan plunging into the water (Figure 1). La Tomba del Tuffatore (The Tomb of the Diver, c. 470 BCE), discovered in 1968 in a cemetery of the Greek city of Posidonia (Roman Paestum, in Southern Italy), has been subjected to multiple symbolic interpretations, from Pythagorean interpretations based on the number of elements represented to the erotic connotations of death by lovers mad with passion jumping from cliffs (katapoutosmos) that we find in several literary works23. Ross Holloway relates the diving into the sea as a transition of the soul from the perils of life to the safety of the eternal symposium, represented in the side slabs of the cist, a motif inspired by similar representations in Etruscan burials (Figure 2)24.

Figure 1. Slab cover of the Tomb of the Diver, Poseidonia, c.470 BCE (modified under Creative Commons)

Figure 2. Detail of the Tomb of Hunting and Fishing, Tarquinia 530-500 BCE (modified under Creative Commons)

This interpretation leads us to a double-faced problem; one that is both philological and archaeological in nature. Like Holloway, many other authors, such as Marie-Claire Beaulieu, interpret diving exclusively in a symbolic way25. But when they refer to diving, they do not mean the underwater world. Diving, understood as leaping from a cliff, and diving, understood as an underwater activity, share the same word in English, which means many authors group two different activities that, while related to the sea, may not have been analogous for their practitioners. In Beaulieu’s book, in which she analyses the symbolic meaning of the sea in ancient Greek culture, all examples but one refer to leaping from a cliff. They represent a rite-du-passage to womanhood, divinity, or statehood (in the case of men). But none of them is a real case of underwater diving. In fact, there are no references to the relative extensive literary records on diving as an economic activity in the book. This mythological interpretation leads us to another issue: the absence of any trace of material culture in the interpretation of these stories and myths. While it is indeed very difficult to find direct references to cliff and underwater diving in the material record, they do exist, and their interpretation is rather mundane. In a recent book, Tonio Höscher analyzes the inscriptions found in rather inaccessible cliff faces on the island of Thasos, which include the typical kalos inscriptions commonly found in gymnasia all around the Greek world, concluding that young males gather there to enjoy a beach day. There is no transcendent jump, no death metaphor, just plunging into the sea for the joy and pleasure of doing so26.

As in the case of Il Tuffatore, in the Etruscan tomb called Hunting and Fishing, we find another diver getting into the water surrounded by other people enjoying other sea-related activities, and, again, the sea is interpreted as the pass to the afterlife. Yet, this interpretation is not applied to the hunting scene, which is interpreted in more mundane terms. For unknown reasons, scholars tend to find in the ocean a mysticism that is not present in their analysis of the land.

3. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The portrayal of divers presented above is not able to transcend the historical narrative due to its inability to “read” divers in the archaeological record. The main reason for this is the scope under which divers are studied. Rather than active agents performing a task, they are portrayed as artifacts, passive objects of literary study that are not able to provide us with, due to the perishable nature of their task, enough data to reconstruct their social and economic role in the past. In order to succeed in the task of increasing the visibility of divers in the archaeological record, it is necessary to abandon this passive perspective and provide a new theoretical framework based on two main concepts: Middle Range Theory and Flow Models of Evidence in Behavioral Archaeology.

Lewis Binford first introduced the concept of Middle Range Theory (MRT) in the early years of Processual Archaeology27. After careful observation of present-day communities of hunter-gatherers, he concluded that they could provide us with first-hand examples of how similar tasks may have been performed in the past. MRT emphasized the use of what came to be known as ethnoarchaeology but also triggered a debate on the risk of projecting ideas and interpretations directly from the present to the past28. There seems to be no distinction in ancient Greek between diving, swimming and plunging, as the verb kolumbao shows, and this induces modern translations to use the terms interchangeably, making tracing back textual evidence more difficult (Table 1). It is interesting to notice how authors will distinguish “general” divers from sponge-cutters even in the same text, using the term dutes for the first ones and spongotomos for the second ones, emphasizing the specialization of the latter and their important economic role29.

Kολυμβάω |

To swim, to dive, to plunge. |

Kόλυμβος |

A swimmer, diver. |

Kολυμβητήρ |

A swimmer, diver. |

ͻΑρνευτήρ |

A plunger into the sea. |

Κυβιστάω |

To throw oneself headmost, to plunge headlong into water, to dive. |

Κυβιστητήρ |

A jumper, a diver. |

Σπογγoτόμος |

Sponge-cutter. |

Δύτης |

Diver |

Table 1. Some terms related to diving in ancient Greek

The second theoretical perspective used in this study applies the Flow Models of Evidence (FME) from Behavioral Archaeology to contextualize our information. In an extremely brief description of this theory, we can state that at any given time, a series of interactions between individuals and material culture occur (systemic context). When this human behavior stops, we are left with a set of material culture in a spatial matrix (archaeological context). The emphasis is made on human behavior, with divers as active agents rather than passive objects of study, with the interaction between humans and their environment mediated by technology. One of the founders of Behavioral Archaeology, Michael Schiffer, defined technology as “[…] a corpus of artifacts, behaviors and knowledge for creating and using products that is transmitted intergenerationally”30. This definition goes beyond the scope of the analysis of material culture to include social and symbolic aspects not only in the transmission but also in the very practice of technology. Only by providing us with a theoretical framework can we provide us with a tool that can help us avoid the analytical limitations of previous studies, which could not correlate the textual evidence with the possible material traces in the archaeological record.

4. WHAT DO WE ACTUALLY KNOW ABOUT ANCIENT DIVERS?

The advantage of applying a new theoretical framework to the study of ancient divers is twofold: on the one hand, we can recover important misread evidence from the archaeological record and return it to its proper context, which can help to provide us with a more accurate vision of ancient divers and, on the other hand, to generate new evidence about divers and their feats. This work provides several examples of misread and hidden evidence on the archaeological record, but before dealing with them, let us consider the most obvious premise of all: divers in the past were human beings.

4.1. Physiological stresses in ancient divers

All physiological stresses affecting modern divers affected sponge collectors and subsistence divers in the past. Data collection regarding this topic is conditioned by the preservation bias that favors the presence of hard tissue rather than soft tissue in the archaeological record. Since the development of apnea as a competitive sport, studies on the physiological effects of freediving in the human body have flourished, explaining the reasons why those depths can be reached and the damages that can be caused to several tissues. Although decompression sickness is less of a risk for freedivers than SCUBA divers due to the alveolar collapse caused by the hydrostatic pressure31, there are several common risks to all divers, such as narcosis, haemoptysis and hypoxia (“blackout”). Every past and present diver must also equalize to relieve the pressure on the eardrums, which can be damaged due to the repetition of dives or the temperature of the water.

These risks affect mostly soft tissue, and when they take place, the diver might pay with his/her life. Nevertheless, even if the natural (e.g. arid landscapes, anaerobic conditions) or cultural conditions of the preservation (e.g. mummification) provide us with access to soft tissue, the short time between the accident and the deposition of the body cannot allow for any trace to be left in the body that could withstand the passing of time. Only when diving takes place repeatedly during the subject’s lifetime and even by generations we can expect an evolution of the soft tissue to adapt to the water. This is the conclusion that Melissa A. Ilardo and colleagues have reached after studying the genetic adaptations to diving among the Bajau people, a group of sea nomads from Southeast Asia, especially the Philippines32. This study concludes that natural selection on genetic variants has favored PDE10A, a gene that increases the size of the spleen, and the BDKRB2, which affects the human diving reflex. A larger spleen provides an extra reserve of blood cells to the diver that gets activated underwater, but -and this is the significant element in evolutionary terms- there are not statistically significant differences between those Bajau engaged in diving and those with a more land-based subsistence. Measurements of spleen size could be taken for other groups, such as the Chinchorro, in South America, which mummified their deceased and for whom other methods have assessed the practice of apnea33.

Aristotle addressed the problems of equalizing, indicating that to avoid the problem, divers pierced permanently their eardrums, a behavior Frost paralleled with some practices among pre-industrial divers. However, he did not provide a specific example, nor did he explain how the pierced eardrum was prevented from healing and closing up again34. Oppian recorded that, on some occasions, divers emerged with their faces covered in blood and their noses bleeding profusely due to the changes in pressure35. His description matches that of haemoptysis after breath-hold diving, caused by a rapid rise to the surface at depths of not even 25 m36.

However, our understanding of many other references to divers is limited by the lack of knowledge about apnea by ancient authors and modern scholars dealing with the translation of these texts. The convoluted explanations of the philological origin of the term urinator, used to refer to professional Roman divers, try only to forcibly ignore its association with urine, which Oleson relates to the effect of cold water diuresis37. The food restrictions and breathing exercises that Oppian describes taking place before diving38, compared to those performed by singers in choral competitions, are remarkably similar to the same routines of sleep, food ingestion and breathing techniques based on the diaphragm performed by competitive freedivers nowadays39.

4.2. The Tools of the Trade

As stated above, a diver’s tools were common and, in most cases, made of perishable materials, leaving a limited record to work with. However, careful examination of this record allows us to provide material evidence for this trade. Although several authors provide more or less extensive references to the work of divers, the texts of Pliny and especially Oppian present the most complete descriptions of the topic40. Both writers are relatively late sources (1st and 2nd c. CE, respectively), but the tools and techniques described in their works are also mentioned in earlier authors, so it is plausible to infer that their descriptions of diving can be applied, to some extent, to earlier periods. Oppian provides the most complete of these descriptions and considers that divers have the worst and most woeful of works:

“A man is girt with a long rope above his waist and, using both hands, in one he grasps a heavy mass of lead and in his right hand he holds a sharp bill, while in the jaws of his mouth he keeps white oil. Standing upon the prow he scans the waves of the sea, pondering his heavy task and the infinite water. His comrades incite and stir him to his work with encouraging words, even as a man skilled in foot-racing when he stands upon his mark. But when he takes the heart of courage, he leaps into the eddying waves and as he springs the force of the heavy grey lead drags him down. Now when he arrives at the sea bottom, he spits out the oil, and it shines brightly and the gleam mingles with the water, even as a beacon showing its eye in the darkness of the night. Approaching the rocks he sees the sponges which grow on the ledges of the bottom, fixed fast to the rocks; and report tells that they have breath in them, even as other things that grow upon the sounding rocks. Straight away rushing upon them with the bill in its stout hand, like a mower, he cuts the body of sponges, and he loiters not, but quickly shakes the rope, signaling to his comrades to pull him up swiftly. For hateful blood is sprinkled straightforward from the sponges and rolls about the man, and many a times grievous fluid, clinging to his nostrils, chokes the man with it is noisome breath. Therefore swift as thought he is pulled to the surface; and beholding him escaped from the sea one would rejoice at once and grieve and pity: so much are his weak members relaxed and his limbs unstrung with fear and distressful labor. Often when the sponge-cutter has leapt into the deep waters of the sea and won his loathly and unkindly spoil, he comes up no more, unhappy man, having encountered some huge and hideous beast. Shaking repeatedly the rope he bids his comrades pull him up. And the mighty sea-monster and the companions of the fisher pull at his body rent in twain, a pitiful sight to see, still yearning for ships and shipmates”41.

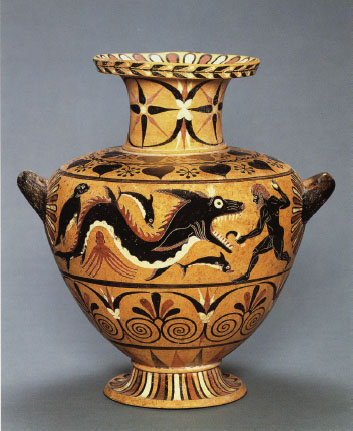

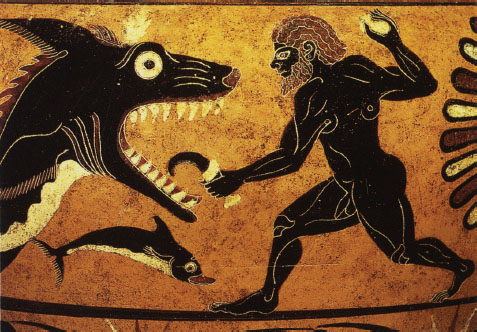

From this text, we can list several tools used by divers, namely knives and bills, lead weights, ropes, oil, and, to reach the sponge beds, a boat. This passage does not mention net bags, but their relationship with divers is well-attested. All these elements can be found in the archaeological record and associated with divers if the theoretical model presented above is applied. The best example of misidentification is provided by a famous and thoroughly published Caeretan hydria dated c. 525-510 BCE that belongs nowadays to the private collection of the Niarchos Foundation42. Unfortunately, the looting of the artifact has deprived us of any contextualized information beyond the fact that its manufacturing, as its name indicates, is associated with the Etruscan city of Caere, present-day Cerveteri. The vessel, especially its marine decoration, has been the object of multitude of studies and discussions regarding the nature of the scene presented in its Side A. On it, a sea creature, always identified as a ketos, or sea monster, is fighting a heroic figure (Figure 3), identified as Perseus by Isler and Herakles by Boardman, even though no attributes associated with these characters are present in the scene43. Both heroes have mythological feats ascribed to them regarding the liberation of a princess from a sea monster. Other authors such as Hemelrijk44 or Marangou45, who published the catalog of the Niarchos collection, consider the male figure an anonymous hero, and the scene probably the representation of an unknown myth from the Ionian city of Phokaia, due to the presence of a seal on the scene (phoke in Greek) and the Ionian style displayed by the Eagle painter, the craftsman to whom the decoration of the vessel is ascribed. None of them considers side B of the hydria, which presents a hunting scene in which a man, who has never been interpreted as a heroic figure, chases a deer and a goat accompanied by a dog. The possibility of the human figure representing an actual diver is never considered (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Caeretan hydria, 520-510 BCE. Side A, a human figure fighting a sea monster.

Note the seal on the left side of the scene (Marangou 1995)

Figure 4. Caeretan hydria, 520-510 BCE. Side B, the hunter and his dog (Marangou 1995)

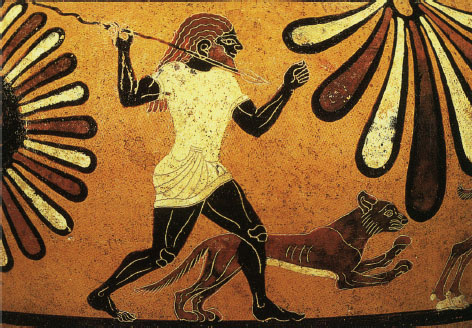

The symbolic interpretation of this hydria is much simpler, especially if we analyze both sides of the vessel together and relate them to the cultural context they belonged to. The combination of fishing and hunting scenes are common motifs in the funerary tradition of the Etruscans, the region from which the hydria is considered to have been manufactured. In this context, and in the absence of any heroic references or symbols, the more straightforward explanation of the scene is that it represents a diver fighting a dogfish. The tendency to interpret as heroic or mythological any scene in which the topic remains unclear is not uncommon in classical archaeology, and it leads to common misinterpretations that obscure and make our access to any reference to divers difficult. A pottery fragment can also illustrate this point recovered on the island of Chios. Relief pottery of the Archaic period has received significantly less attention in scholarship than the better-known examples of painted pottery. However, when this style is assessed, it is not uncommon to be illustrated by the sherd presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Relief pythos from Chios, c.550-525 BCE (picture by Thierry Jamard)

This fragment of a pythos has been dated c.550-525 BCE, and the figure represented below the molded frieze has been interpreted as a triton or a merman: a mythological figure, its marine nature determined by the octopus he holds in its right hand46. Note, however, that the piece is broken on the waist, so it is not possible to know whether the lower part of the body was a fishtail or a pair of legs. Why does it have to be a merman, then? Although this issue is never explicitly addressed, the main reason is that the figure of a man fishing an octopus just by hand seems too fantastic to be real for the scholars describing the piece, hence, the mythological creature. In fact, in the world’s oceans, we can find examples of traditional divers and modern spearfishers fishing octopuses with bare hands, killing the animal by baiting their head between the eyes (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Baja Lau diver fishing an octopus without tools (James Morgan at the Daily Telegraph)

Returning to the Caeretan hydria, this vessel belongs to the broader Etruscan tradition of fishing and hunting scenes, such as those we have already explored in the funerary frescoes, and this diver is no hero, in the mythological sense, but a spongotomos fighting one of his most common threats, a dogfish. He defends himself with a harpe, a curved knife resembling a bill hook, a common agricultural implement used for pruning and as a multi-purpose tool (Figure 7). However, its sickle-shaped blade makes it a very useful tool for harvesting sponges, cutting them off with a single circular motion of the arm, reducing the oxygen consumption underwater.

Figure 7. Detail of the diver fighting the shark with a harpe (adapted from Marangou 1995)

It could be argued that, lacking proper excavation context, it is not possible to identify harpai used by divers as opposed to harpai used by farmers, but it is important to notice that several museums in Greece have in their deposits examples made of bronze and this material is an indicator of at least its maritime nature. By this date, iron, not bronze, was the standard metal in tool manufacturing due to its better overall resistance and performance and its price, since the necessary copper and tin to make bronze were, especially in the case of the second, luxury commodities. Nevertheless, a harpe made of bronze would have been an advantage to a diver due to the corrosive effect of seawater in a knife made with the low-carbon iron characteristic of this period.

Another element to analyze is the white object carried out by the diver in the left hand. Marangou and Hemelrijk interpret it as a stone the figure is throwing to the monster from the shore (none of them consider the action taking place underwater despite the multiple animal figures surrounding the dogfish)47. Oppian mentions using lead weights, which corrode with a white crust, but it is impossible to ascertain that the amorphous object represented might be one of these weights. There are, however, examples of lead weights that could be used for diving in the archaeological record.

Stone anchors used by boats and ships are, after amphorai, the most common find on underwater excavations, but the reference to lead ship anchors is much more scarce. One find, however, recovered from the sanctuary of Aphrodite in the demos of Myrrhynous, provides us with another example of a misinterpreted artifact. At the moment of its discovery in 1999, no date or dimensions were reported, and the object was first identified as a lead model of an anchor dedicated by a certain Lysimachos as the inscription apparently indicated (Λυσιμα(χ- - -)) (SEG 563 224) (Figure 8). This interpretation presents a major problem since careful examination of the artefact shows no grounds to consider any character missing. Hence, a second interpretation of the graffito was provided in 2007 by O. Kakavogianni, reading Λύσιλλα instead of Lysimachos (SEG 57 291) and providing a date for the object of 4th c. BCE. Because it contains a female name, the artifact is now reinterpreted as a loom-weight.

Figure 8. Lead weigh exhibited in the Archaeological Museum of Vravrona, 4th c. BCE (picture by the author)

This is perhaps one of the best-known examples of gender bias in the archaeological record. The object is now on display in the archaeological museum of Vravrona (where it is still labeled as an anchor), waiting for a more detailed publication that could provide us with the dimensions and weight of the object. In the meantime, I interpret it as a diver’s weight dedicated by a woman called Lysima (there is no reason to read a double lambda since the angle and the overlapping chiseling both clearly denote a single character) in the sanctuary of Aphrodite that, by the influence of the Phoenician Astarte/Isthar, was considered in many communities as a sea goddess. An estimation of the weight based on its dimensions (between 2 and 3 kg) indicates that it has the right size to allow a skin diver to break the positive buoyancy of the first meters of the dive without accelerating the descent at such a speed as to make equalization not possible or very painful. The ethnographic record offers multitude of examples of communities in which women practice diving, in some cases exclusively, such as the Ama of Japan and the Haneio of Korea48, or the Alacaluf and Yaghan of Chile49. In the historical record, we have seen how Hydna participated in the attack on the Persian fleet at Artemission, and Pausanias also records a tradition by which only pure virgins (parthenoi) may dive into the sea50.

Other lead artifacts recovered in the Mediterranean have been identified as diver weights51. However, Piero Gianfrotta already pointed out the problem of distinguishing examples used for diving and/or other fishing activities if they are not recovered in very specific contexts52. In a publication presenting several finds of remotely operated artifacts for recovering objects from the sea Ehud Galili and Baruch Rosen considered that salvaging rings, made of lead and used to recover lines stuck into the reefs, could have had a second life as weights for divers53. A significantly more systematic analysis, including experimental diving sequences with these tools, has recently been published by Hakan Oniz and Ahmet Denker,54 including examples made of lead but also marble.

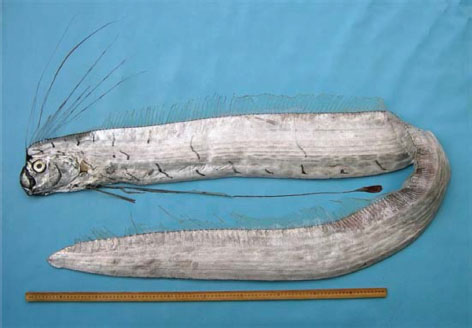

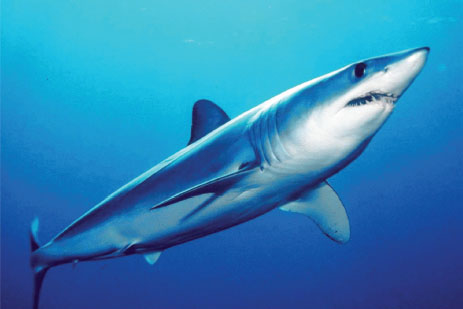

The last element to be discussed from the Caeretan hydria is the sea creature that attacks the diver, which provides more evidence for the subaquatic interpretation of the scene. The pisciform monster has been generally identified as a ketos, a name that includes both mythological creatures and any large marine creature such as whales or large fishes. In a recent paper, John Papadopoulos55, who has published extensively on the biological nature of many of these monsters56, has interpreted this creature as a Pelagecus glesne, an oarfish, a deep water creature (100-1000 m)57, that can be occasionally captured by nets in shallower waters and that can reach up to 11 m. The reasons argued for this identification are the serpentine body, the lack of scales and the dorsal fin, as well as the general naturalistic character of the rest of the animals represented. The problem with this identification is that it requires as many aspects to be ignored as to be identified, especially regarding the head of the creature, and the author admits this is an artistic license in an otherwise naturalistic representation of the oarfish. The real oarfish has very small fins and jaws, which clearly contrasts with the image in the hydria (Figure 9).

Figure 9. An oarfish washed ashore the coast of California. Note the differences with the ketos, especially regarding the morphology of the head (modified under Creative Commons)

The ketos is, in fact, a dogfish, a shark. Although the red dorsal fin and perhaps the red traces on top of the head may resemble those of an oarfish, the large jaws, teeth and fins, the size and position of the eyes, the absence of scales, the red lines that represent the gills, and the contrast between the darker upper part painted black and the lighter lower part of the body painted white, could suggest an Isurus oxyrrinchus, a shortfin mako shark, an endemic species of the Mediterranean sea58 (Figure 10). However, other sharks are known to inhabit the region, and the representation is quite probably a generic one. There is no question that the upper part of the head has more characteristics of a mammal than a marine creature. Nevertheless, this depiction only emphasizes the identification of this creature as a dogfish, especially due to the nozzle painted in red (Figure 11). Encounters between divers and sharks were recorded in antiquity, and, even then, divers knew that the most effective way to survive a shark attack was to attack its nozzle59.

Figure 10. Isurus oxyrrinchus, a short fin mako shark. (modified under Creative Commons)

Figure 11. Detail of the sea-monster. Note the morphological similarities to the mako shark, especially regarding the chromaticism of the body, the relative proportion of fins and head (adapted from Marangou 1995)

Shark attacks are not unknown in either the archaeological or literary records. In a scholion to Aeschines, the death of an initiate of the Eleusinian Mysteries is recorded during the second day of the ritual, consisting of a bath into the sea60. Plutarch may have preserved the same event, but the dates do not match61. The very famous Late Geometric Cratere del Naufragio found at the Necropolis of San Montano shows a sailor attacked by a very large fish, which has already eaten his head, a scene that reminds of the epigram written by Leonidas of Tarentum (born c. 325 BCE) to a sailor called Tharsys, who descended into the sea to recover an anchor and, right before reaching the safety of the boat, is killed by a shark, who devoured him waist down62.

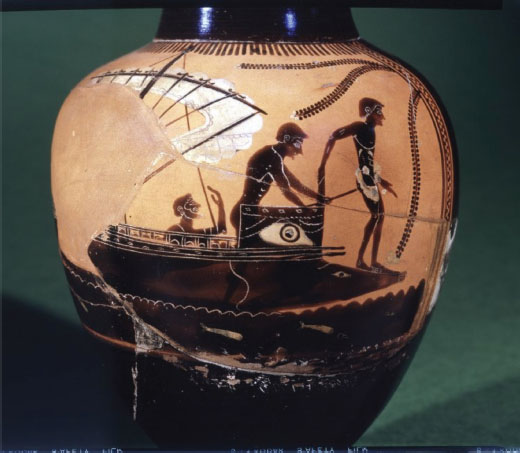

For the use of ropes, we need to rely on another scene from Greek pottery, in this case, an Attic oinochoe dated between 510-490 BCE, excavated at Vulci (Etruria) and deposited today in the British Museum. In the scene, a figure is standing on the prow of the ship with a rope attached to his waist that projects back to the hands of a second figure inside the boat. Although the scene can be interpreted as a diver getting ready to get into the water, the weight of interpretative tradition that seeks a mythological meaning relates the scene to the landing of Protesilaos at Troy, even though no indicator of a hero, a city or a war can be found in the scene (Figure 12). Ropes and nets were made in linen or flax, and under usual conditions will last only for 2 or 3 months; beyond that, repairing became fruitless. This constant manufacturing and repairing of nets has provided us with a more tangible find: myriads of bronze netting needles of the “Mediterranean” type, a slim road with forks at both sides63 (Figure 13).

Figure 12. Athenian Black Figure oinochoe, c.510-490 BCE. Courtesy of the British Museum, 1867,0508.964

Figure 13. Hellenistic netting needle from the Archaeological Museum of Corinth; length 161 mm, thickness 3mm, width of the forks 11 mm (Photo by the author)

Nets were used to collect sponges, coral and seashells underwater. T.B.A. Spratt describes a sponge collectors bag as having a long loop that goes around the neck64, and an example of this net can be found, according to Heinz-Eberhard Giesecke in the fresco of the West House at Akrotiri65. Although the traditional interpretation of this scene is that of a naval battle and sailors being tossed off the ships with weights on their necks66, Gieseke reinterprets it as a group of divers with net baskets around their necks collecting the coral represented on the reef (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Possible scene of divers collecting coral, detail of the West House at Akrotiri (Creative Commons)

These bags are usually characterized by a spherical shape and a wide opening to facilitate the introduction of goods. Although the name of several nets has been preserved in historical sources, it is unclear which one corresponds to the net bag used by divers. Ross Thomas suggests the hypoche perigee 67, but as Tønnes Bekker-Nielsen points out, this design could be some kind of scoop68. The sphairon, which for him is a passive net, is interpreted by Carmen Alfaro as a casting net69. Despite these issues of identification, we can still find some examples of nets that may resemble the net bag used by divers, such as the one for carrying goods recovered from the excavations of Myos Hormos in Egypt, by the Red Sea70 or the net bag that fishermen carry in several Athenian vessels (e.g. Ashmolean Museum 1919.26). These could be identified as the gangamon mentioned by Oppian71. These nets have a very long history, and, with slight differences, they appear in all cultures in which diving was an important economic activity. The pearl divers described by Isodore of Charax use the same net bag to collect oysters in the Persian Gulf72, while frescoes decorating dwelling structures in Teotihuacán depict divers collecting oysters with a net around their neck73 (Figure 15).

Figure 15. Fresco of Teotihuacan depicting a diver gathering oysters with a net around his neck. 300-600 CE. Photo courtesy of Dr. Jessica McLellan

Two elements related to diving mentioned in the literary sources have caused multiple interpretative problems for scholars working with those texts. Aristotle describes what seems to be some kind of snorkel made with reeds and a lebes or cauldron in the water to give an extra air lung74. Concerning the snorkel, the arundo donax, a reed plant used in ancient times for musical instruments, can reach a diameter of 20-30 mm; most present-day snorkels measure between 15 and 25 mm. He also mentions that divers, while using them, resemble elephants in the water while using their trunks for breathing, an image that resembles some of the new swimming frontal snorkels in the market. Although snorkels are only operative at very shallow depths, ancient and modern examples are used not for breathing underwater but for allowing the diver to stay with the head down, scouting the sea floor. Regarding the cauldron, it is not explained very clearly how the diver may have dealt with the differential pressure of the air breath from the cauldron once this was submerged.

The second element is a reference in Oppian75 and Plutarch76 to divers’ use of olive oil to increase visibility underwater. Divers would keep a mouthful of oil or a sponge with oil in their mouths and spill it out once the bottom was reached to take advantage of the reflecting properties of the oil and illuminate dark spots. Frank Frost, however, diminishes this technique as ancient divers teasing the writers and concludes that the oil was used to protect the ears from cold water by circulating it through the sinuses77. Aristotle reports the use of small sponges to protect the ears, but more research is necessary to understand how these sponges could have affected equalization78.

Divers could have entered the water by the shore or, as we have seen in several artistic representations, by jumping from rocks and cliffs, but a boat would have been necessary to reach the richest and less exploited areas. There are many representations of small fishing boats, especially in Greek painted pottery, but the discovery of a 6th c. BCE boat in Marseille (Jules Verne 9 wreck) and the reconstruction of this boat made by a team of researchers led by Patrice Pomey offers us the most direct insight into the performance of a Greek fishing boat of the Archaic period. The Jules Verne wreck was excavated in 1993 in Place Jules Verne, which occupies the area of the ancient harbor of the Greek colony of Massalia. It was a coastal boat of c. 10 m in length used for fishing red coral, as the small fragments recovered from the hull indicate79. The state of preservation of the hull and the ligatures that stitched the planks together (called sewn technique), encouraged the reconstruction of a sailing replica, the Gyptis, with which to perform tests on the capabilities of this boat80. These results are an invaluable archaeological and ethnographic insight into the labor organization of these crews, which were directly involved in the harvesting of red coral.

5. THE EXPLOITATION OF MARINE SOURCES

The study of the products harvested by divers can also provide us with extensive evidence of their activities and the economic role they played in their society. The presence of marine species that can only be accessed by means of diving is one of the easiest ways to detect divers’ presence in a community. The first divers exploited goods such as shellfish, which are preserved rather well in the archaeological record thanks to the calcium carbonate of shells. However, as it has been mentioned above, the most skillful divers were able to capture fish. We ignore the use of other tools by divers to capture them; small bronze tridents and forks have been recovered in the archaeological record, and several ancient authors wrote about the capture of fish underwater, but no direct evidence has been clearly established yet81. Present-day spearfishers pierce octopuses in hidden crevices with small tridents and kill them by biting them between the eyes, so it is at least feasible that some of these small tridents could have been used underwater. John M. McManamon interprets another epigram of Leonidas of Tarentum82 as a direct reference to this practice when the poet describes the late fisherman as a “prober of crevices”, a description that matches this spearfishing technique83. Examples of tridents and harpoons (also made in bronze to endure seawater corrosion) are relatively common finds in archaeological contexts where the exploitation of marine sources played a significant role84.

That diving was considered to be an old activity is indicated by the several myths that take place underwater. On his way to Knossos to fight with the Minotaur, the Athenian hero Theseos, to prove King Minos the gods favored him, had to dive into the palace of the goddess of the sea Amphitrite85. Bacchylides probably dedicated this ode to the god Apollo in his sanctuary in the Delos island, famous for its divers86. According to Pausanias, the inhabitants of Hermione devoted themselves to the traits of the sea, including the collection of murex87, and celebrated a diving competition during the festival in honor of Dionysos Melanaigis88.

Although the fisher that eventually dove to collect other seafood never disappeared, the increase in the demand for some products triggered the appearance of full-time divers who specialized in collecting murex for purple dye, red coral, pearls, and sponges. The over-exploitation of the two first probably depleted the beds accessible to divers, and new devices and methods were developed for its collection89. Although it has been claimed that the basins found in dye factories were devoted to the breeding of murex, there is not yet convincing evidence based on the biology of this species to support that interpretation, and it is possible that these basins were used for preprocessing storage90. But even if such breeding basins existed, it is clear that, at least in origin, the collection of murex was carried out by divers since this mollusk lives in depths between 4 and 150 m. On the other hand, Sponges regenerate faster than the population of murex or corals, especially if seasonal harvesting cycles are imposed, as is the case in many traditional diving communities91. Pealing was especially important in the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf from very early times92, although it significantly increased during the Roman Empire93.

There is a last source divers exploited, although its evidence in the archaeological record is elusive: the Fan mussel, or Pinna nobilis. This large bivalve (30-50 cm, but can reach up to 120 cm) attaches itself to rocks between 0.5 and 60 m deep, using a strong byssus, a very strong animal fibre that, once treated and exposed to sunlight, acquires a golden reflect. Although this “sea-silk” is mentioned in classical works, not much research has been devoted to it, presumably due to the difficulties involved in its preservation. It was, however, a very important commodity, and it was taxed as such in the edict of Diocletian Edictum de Pretiis Rerum Venalium (301 CE).

Sponges were undoubtedly the most commonly exploited of all the products harvested in the sea. Their direct presence in the archaeological record is not common although possible, and while post-depositional processes affect their preservation, careful recovery techniques, or the lack of them, may be the main reason for their absence, as the findings of sponges in Brandeam (Hampshire) and York indicate94. Indirect proof of its use is early and abundant; an example is the texture of a Middle Minoan IIA wall from the North West Portico at Knossos, decorated with a pattern obtained by pressing a sponge on the wet plaster95. The use of sponges in forming and finishing pottery is also well-attested, and sponges, corals, and other marine motifs are common decorative elements in painted pottery from the Bronze Age onward.

Despite this artistic source, their main use was related to medicine and hygiene. In a detailed survey of the use of sponges in ancient authors, Eleni Voultsiadou provides us with a comprehensive list of the application of sponges, in which medicine, especially the works assigned to Hyppocrates (5th c. BCE), take a central role. It is important to remember that up to the appearance of synthetic components, sponges were the only materials that could perform some medical tasks96. If we consider how extended the use of sponges was in medicine, and we infer from there their commercial importance, then the addition of the evidence for the use of sponges as elements of personal and household hygiene only adds to the ubiquity of this product across the Mediterranean and, in later centuries, to the Roman empire, from baths to latrines.

6. NEW DEPTHS

This study has demonstrated that if low-visibility communities are studying under a light that emphasizes the importance of the contributions of anthropology in the development of archaeological theory, we can provide a much more detailed picture than the one with which this research started. Despite this achievement, it is not possible to ignore a very important reality regarding the nature of the record: it is fragmentary and decontextualized. The collection of data and artifacts, mostly from museum collections, is painstakingly slow due to the misidentification of these objects, making each discovery an isolated event. These are all important contributions to our knowledge not only of divers and the economic role they played in their societies, and more research on their technology must be encouraged for other cultures of the Mediterranean such as the Carthaginians, the Etruscans or the Phoenicians, who were regarded as the main producers of purple-dye. Research on traditional divers must be also encouraged, emphasizing especially the material aspects of their work and their life as a whole, with the intention of providing an analytical framework against which our dataset can be compared. Nevertheless, if we really are expected to understand the life and work of ancient divers, we need to excavate settlements in which diving was one of the central elements of society and economy.

The state of this research allows us to select three possible candidates for this study: the island of Delos, the waters of the Saronic gulf between Hermione and the island of Hydra, which belonged to Hermione until the 6th c BCE and then to Troezen, and, especially, the city of Anthedon in Boeotia. This settlement opposite to the south coast of Euboea was famous in antiquity for its divers, who collected from the sea murex and sponges97. Glaukos, a mortal transformed into an undersea god by Dionysos and patron deity of sailors and divers, was considered to be from this village and also had an oracle on the island of Delos. He became a god after diving to the bottom of the sea and collecting a plant that he ate98, a story that vividly resembles the legend of the Babylonian hero Gilgamesh99. Excavations were carried out in the acropolis of Anthedon in the winter of 1888-1889 by John Rolfe, but those focused only on the discovery of the general layout of a small temple100. In the excavated deposits, we can find some of the artifacts we discussed earlier, such as bronze harpai, but apart from these “testing” works, the site remains unexcavated. The economic activities of Anthedon and the ritual practices in its sanctuary to Glaukos, in which we may presume the Anthedonian divers deposited offerings, can provide us with the contextualised dataset this topic needs in order to advance further in our understanding of the ancient freediving community.

REFERENCES

Aeschines. Speeches: Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 1919.

Aristotle. Problems, Volume I: Books 1–19. Translated by Robert Mayhew. Cambridge, Mass, 2011.

Ashburner, Walter. The Rhodian Sea-Law. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1909.

Bekker-Nielsen, Tønnes. “Fishing in the Roman World”. Classica and Mediaevalia 53 (2002): 215–233.

Bernal Casasola, Darío. “Fishing Tackle in Hispania: Reflections, Proposals and First Results”. In Ancient Nets and Fishing Gear, Proceedings of the International Workshop on “Nets and Fishing Gear in Classical Antiquity: A First Approach”. Cadiz, November 15–17 2007, edited by Tønnes Bekker-Nielsen and Darío Bernal Casasola, 82–137. Cadiz: Universidad de Cadiz and Aarhus Press, 2010.

Bernard, H. Russell. “Kalymnos: The Island of the Sponge Fishermen”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 268 (1976): 289–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb47652.x

Binford, Lewis R. “Archaeological Systematics and the Study of Culture Process”. American Antiquity 31 (2) (1965): 203–210. https://doi.org/10.2307/2693985

Boardman, John. Athenian Red Figure Vases: The Classical Period. London: Thames & Hudson, 1989.

Boardman, John. The History of Greek Vases. London: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Boussuges, A., P. Pinet, P. Thomas, E. Bergmann, J-M Sainty, and D. Vervloet. “Haemoptysis after Breath-Hold Diving”. European Respiratory Journal 13 (1999): 697–699. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.99.13369799

Crowe, Fiona, Alessandra Sperduti, Tamsin C. O’Connell, Oliver E. Craig, Karola Kirsanow, Paola Germoni, Roberto Macchiarelli, Peter Garnsey, and Luca Bondioli. “Water-Related Occupations and Diet in Two Roman Coastal Communities (Italy, First to Third Century AD): Correlation between Stable Carbon and Nitrogen Isotope Values and Auricular Exostosis Prevalence”. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 142 (3) (2010): 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21229

DeVries, Keith. “Diving into the Mediterranean”. Expedition 21 (1) (1978): 4–8. https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/diving-into-the-mediterranean/

Edmonds, John Maxwell. The Fragments of Attic Comedy. Vol. IIIA. Leiden: Brill, 1961.

Fitz-Clarke, John R. “Lung Compression Effects on Gas Exchange in Human Breath-Hold Diving”. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology 165 (2009): 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2008.12.006

Fitz-Clarke, John R. “Mechanics of Airway and Alveolar Collapse in Human Breath-Hold Diving”. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology 159 (2007): 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2007.07.006

Frost, Frank J. “Scyllias: Diving in Antiquity”. Greece & Rome, Second Series, 15 (2) (1968): 180–185. https://www.jstor.org/stable/642431

Frost, Honor. “Bronze Age Stone-Anchors from the Eastern Mediterranean”. Mariner’s Mirror 56, no. 4 (1970): 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/00253359.1970.10658560

Fuchs, W. “The Chian Element in Chian Art”. In Chios, a Conference at the Homereion in Chios 1984, edited by John Boardman and C.E. Vaphopoulou-Richardson, 275–293. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986.

Galili, Ehud, and Baruch Rosen. “Ancient Remotely-Operated Instruments Recovered Under Water off the Israeli Coast”. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 37 (2) (2008): 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047759400018948

Giesecke, Heinz-Eberhard. “The Akrotiri Ship Fresco”. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology and Underwater Exploration 12 (2) (1983): 123–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-9270.1983.tb00121.x

Hemelrijk, J. M. Caeretan Hydriae. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 1984.

Heraclides of Pontus, and H.B. Gottschalk. Heraclides of Pontus. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press., 1980.

Herodotos. Histories. Translated by A. D. Godley. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press., 1922.

Holloway, R. Ross. “The Tomb of the Diver”. American Journal of Archaeology 110 (3) (2006): 365–388.

Ilardo, Melissa A., Ida Moltke, Thorfinn S. Korneliussen, Jade Cheng, Aaron J. Stern, Fernando Racimo, Peter de Barros Damgaard, et al. “Physiological and Genetic Adaptations to Diving in Sea Nomads”. Cell 173 (3) (2018): 569–580.e15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.054

Monro, Charles Henry. The Digest of Justinian. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1904.

Oleson, John Peter. “A Possible Physiological Basis for the Term Urinator, ‘Diver.’” The American Journal of Philology 97 (1) (1976): 22–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/294109

Oniz, Hakan, and Ahmet Denker. “Four Rare Ring-Shaped Artifacts from Antalya and Mediterranean Diver Weights of Antiquity”. Journal of Maritime Archaeology 17 (4) (2022): 559–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11457-022-09343-2

Papadopoulos, John K. “The Natural History of a Caeretan Hydria”. BABESCH 91 (2016): 69–85.

Papadopoulos, John K., and Deborah Ruscillo. “A Ketos in Early Athens: An Archaeology of Whales and Sea Monsters in the Greek World”. American Journal of Archaeology 106 (2) (2002): 187–227. https://doi.org/10.2307/4126243

Paton, W. R. The Greek anthology. Vol. 3. 5 vols. London and New York: London, W. Heinemann; New York, G.P. Putnam’s sons, 1916.

Pelizzari, Umberto, and Stefano Tovaglieri. Manual of Freediving: Underwater on a Single Breath. Rev Upd edition. Reddick, FL: Idelson Gnocchi Pub, 2004.

Pomey, Patrice, and Pierre Poveda. “Gyptis: Sailing Replica of a 6th-Century-BC Archaic Greek Sewn Boat”. The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology and Underwater Exploration 47 (1) (2018): 45156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572414.2021.1943949

Rolfe, John C. “Discoveries at Anthedon in 1889”. The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts 6 (1) (1890): 96–107. https://doi.org/10.2307/496154

Schaus, Gerald P. Review of Review of Caeretan Hydriae, by Jaap M. Hemelrijk. American Journal of Archaeology 89, no. 4 (1985): 701–703. https://doi.org/10.2307/504219

Schiffer, Michael Brian. Behavioral Archaeology. University of Utah Press, 1995.

Spratt, T.B.A. Travels and Researches in Crete. London: John van Voorst, 1865.

Standen, V. G., B. T. Arriaza, and C. M. Santoro. “External Auditory Exostosis in Prehistoric Chilean Populations: A Test of the Cold Water Hypothesis”. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 103 (1) (1997): 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199705)103:1%3C119::AID-AJPA8%3E3.0.CO;2-R

Thomas, Ross. “Fishing Equipment from Myos Hormos and Fishing Techniques on the Red Sea in the Roman Period”. In Ancient Nets and Fishing Gear, Proceedings of the International Workshop on “Nets and Fishing Gear in Classical Antiquity: A First Approach”. Cadiz, November 15–17 2007, edited by Tønnes Bekker-Nielsen and Darío Bernal Casasola, 138–159. Cadiz: Universidad de Cadiz and Aarhus Press, 2010.

Voultsiadou, Eleni. “Sponges: An Historical Survey of Their Knowledge in Greek Antiquity”. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 87 (2007): 1757–1763. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315407057773

1. e.g. Bernard, “Kalymnos: The Island of the Sponge Fishermen”.

4. Ant. Palat. 9.296.

6. Klein, Zur sogenannten Aphrodite vom Esquilin.

7. Andreae, Rhein, and Bucerius Kunst Forum, Kleopatra Und Die Caesaren.

11. Frost, “Scyllias,” 183.

13. Frost, “Scyllias,” 184.

14. Voultsiadou, “Sponges: An Historical Survey of Their Knowledge in Greek Antiquity”; Oleson, “A Possible Physiological Basis for the Term Urinator, ‘Diver’”.

15. Dio Cassius 74 12,1-2.

16. Quintus Curtius 4.4.10-12.

17. Thucydides 4.26.

18. Dio Cassius 46.36.5.

19. Titus Livius 40.5.15.

20. Crowe et al., “Water-Related Occupations and Diet in Two Roman Coastal Communities (Italy, First to Third Century AD)”.

21. The Digest of Justinian 14.2.4.

22. The Rhodian Sea-Law 3.47.

23. e.g. Anacreon fr.21.

24. Holloway, “The Tomb of the Diver”; DeVries, “Diving into the Mediterranean”.

25. Beaulieu, The Sea in the Greek Imagination.

26. Hölscher, El nadador de Paestum, 43–46.

27. Binford, “Archaeological Systematics and the Study of Culture Process”.

28. Schiffer, “Is There a ‘Pompeii Premise’ in Archaeology?”

29. Oppian Hal. 5.612 and 4.593.

30. Schiffer, Behavioral Archaeology, 230; also Schiffer, Technological Perspectives on Behavioral Change, 44.

31. Fitz-Clarke, “Lung Compression Effects on Gas Exchange in Human Breath-Hold Diving”; Fitz-Clarke, “Mechanics of Airway and Alveolar Collapse in Human Breath-Hold Diving”.

32. Ilardo et al., “Physiological and Genetic Adaptations to Diving in Sea Nomads”.

33. Standen, Arriaza, and Santoro, “External Auditory Exostosis in Prehistoric Chilean Populations”.

34. Frost, “Scyllias,” 182; Aristotle Prob. 32.2-11.

36. Boussuges et al., “Haemoptysis after Breath-Hold Diving,” 697.

37. Oleson, “A Possible Physiological Basis for the Term Urinator, ‘Diver.’”

39. Pelizzari and Tovaglieri, Manual of Freediving.

40. Pliny 9.148-153; Oppian Hal. 5.612-674.

42. Marangou, Ancient Greek Art from the Collection of Stavros S. Niarchos.

43. Isler, “Drei Neue Gefässe Aus Der Werkstatt Der Caeretaner Hydrien”.; Boardman, Athenian Red Figure Vases.

44. Hemelrijk, Caeretan Hydriae; Hemelrijk, More about Caeretan Hydria; Schaus, “Review of Caeretan Hydriae”.

45. Marangou, Ancient Greek Art from the Collection of Stavros S. Niarchos; Hemelrijk, Caeretan Hydriae.

46. Boardman, The History of Greek Vases; Fuchs, “The Chian Element in Chian Art”.

47. Hemelrijk, Caeretan Hydriae; Marangou, Ancient Greek Art from the Collection of Stavros S. Niarchos.

48. Rahn and Yokoyama, Physiology of Breath-Hold Diving and the Ama of Japan.

49. Gusinde, Hombres Primitivos En La Tierra Del Fuego.

51. Frost, “Bronze Age Stone-Anchors from the Eastern Mediterranean”; contra Powell, Fishing in the Prehistoric Aegran, 91.

52. Gianfrotta, “Archeologia Subacquea e Testimonianze Di Pesca,” 16.

53. Galili and Rosen, “Ancient Remotely-Operated Instruments Recovered Under Water off the Israeli Coast,” 290.

54. Oniz and Denker, “Four Rare Ring-Shaped Artifacts from Antalya and Mediterranean Diver Weights of Antiquity”.

55. Papadopoulos, “The Natural History of a Caeretan Hydria”.

56. Papadopoulos and Ruscillo, “A Ketos in Early Athens”..

57. Papadopoulos, “The Natural History of a Caeretan Hydria,” 79.

58. Rodriguez-Alvarez, “The Hidden Divers: Sponge Harvesting in the Archaeological Record of the Mediterranean Basin”.

59. Oppian Hal. 5.612-674; Pliny NH 9.148-153.

61. Plutarch Phok. 28.

62. Antol. Palat. 7.506.

63. Alfaro Giner, “Fishing Nets in the Ancient World: The Historical and Archaeological Evidence,” 64; Vargas Girón, “Otras evidencias de instrumental y material pesquero complemetario”.

64. Spratt, Travels and Researches in Crete, 225.

65. Giesecke, “The Akrotiri Ship Fresco,” 151.

66. Powell, Fishing in the Prehistoric Aegean.

67. Thomas, “Fishing Equipment from Myos Hormos and Fishing Techniques on the Red Sea in the Roman Period,” 138.

68. Bekker-Nielsen, “Fishing in the Roman World,” 217–18.

69. Alfaro Giner, “Fishing Nets in the Ancient World: The Historical and Archaeological Evidence”.

70. Thomas, “Fishing Equipment from Myos Hormos and Fishing Techniques on the Red Sea in the Roman Period”.

72. Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists, 1:3.93E.

73. Donkin, Beyond Price: Pearls and Pearl-Fishing: Origins to the Age of Discoveries, 298.

74. Aristotle Parts of Animals 2.16.

76. Plutarch De Primo Frigido 950B.

77. Frost, “Scyllias,” 182.

78. Aristotle Problems 32.3, 32.11.

79. Pomey, “Les Épaves Grecques et Romaines de La Place Jules-Verne à Marseille”.

80. Pomey and Poveda, “Gyptis: Sailing Replica of a 6th-Century-BC Archaic Greek Sewn Boat”.

81. Oppian Hal. 4.593-596; Heraclides of Pontus 1.23-24.

82. Antol. Palat. 7.295.

83. McManamon, Neither Letters nor Swimming””, 1.

84. Castanyer, “Les Arts de Pesca a Empúreis”; Gutierrez and Giles, “37.- Útiles de Pesca de La Factoría de Salazones P-19 (Anzuelos, Ganchos y Punta de Arpón Tipo Macalón)”.

85. Bacchylides 17.

86. Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists 7.295.

88. Plutarch Alex. 36; Strabo 8.6.12.

89. Galili and Rosen, “Ancient Remotely-Operated Instruments Recovered Under Water off the Israeli Coast”; Bernal Casasola, “Fishing Tackle in Hispania: Reflections, Proposals and First Results,” 128.

90. Marzano, Harvesting the Sea, 146.

91. Kito, “Review of Activities: Harvest, Seasons and Diving Patterns”.

92. Caspers, “Corals, Pearls and Prehistoric Gulf Trade”.

93. Schörle, “Pearls, Power and Profit”.

94. de Grossi Mazzorin, Archeozoologia. Lo Studio Dei Resti Animali in Archeologia., 5–6.

95. Powell, Fishing in the Prehistoric Aegean, 89.

96. Voultsiadou, “Sponges: An Historical Survey of Their Knowledge in Greek Antiquity”.

97. Pausanias 3:9.22.6, Strabo 4.04.

98. Ovid Metamorphoses 7.232-233; 13.903.

99. George, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic, 9.273-293.