Teaching English to Students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

La enseñanza del inglés al alumnado con TDAH

Ana Mª Pérez-Cabelloa(*), Margarita Gil-Pérezb, Francisco Jesús Oliva-Pérezc

a Departamento de Didáctica de la Lengua y de la Literatura y Filologías Integradas, Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, España.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9650-9730aperez40@us.es

b Departamento de Didáctica de la Lengua y de la Literatura y Filologías Integradas, Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, España.

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-6069-8562margilper@alum.us.es

c Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, España

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-6097-6560olivaperezfran@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This research aims to study how teaching English to students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is developed and adapted. This study will allow us to discover the most effective strategies and methods to improve the teaching of L2 for ADHD students. To this end, a survey is delivered to English teachers in 8 schools in Condado de Huelva (Andalusia, Spain). Results show how teachers adapt their teaching favourably to these children. They employ various measures, strategies, and methods to provide ADHD students with skills to acquire English. Results are consistent with other researchers´ studies on teaching English to ADHD students. They show that these methods and strategies best suit students’ attention and movement needs.

Keywords

ADHD, English, methodology, strategies, methods, teaching

RESUMEN

Este trabajo persigue estudiar el desarrollo y adaptación de la enseñanza de inglés al alumnado con Trastorno por Déficit de Atención e Hiperactividad (TDAH). Dicho estudio nos permitirá descubrir las estrategias y métodos más efectivos para mejorar la enseñanza de inglés a estos estudiantes. Para ello, se realiza una encuesta destinada a docentes de inglés de 8 centros educativos de la zona de Condado de Huelva (Andalucía, España). Los resultados muestran que el profesorado adapta favorablemente la enseñanza del inglés a estos escolares. Emplean una serie de medidas, estrategias y métodos que resultan útiles para dotar a estas personas de las destrezas necesarias para la adquisición del inglés como L2. Estos resultados concuerdan con otras investigaciones sobre el tema. Muestran que estos métodos y estrategias son los que mejor se ajustan a las necesidades de atención y movimiento que requieren estos estudiantes.

Palabras clave

TDAH, inglés, metodología, estrategias, métodos, enseñanza

1. Introduction

The approach to teaching L2 is very complex. This complexity is accentuated in students with difficulties. Specifically, this research addresses ADHD students. Pelaz and Autet (2015) indicate ADHD “is the most frequent neuropsychiatric disorder in childhood” (p. 57)1. It is estimated that about 10% of child population suffers from ADHD (Konicarova, 2014). This neurodevelopmental disorder directly influences the teaching-learning process of ADHD students.

The lack of medical and specialised attention required by ADHD students and their families and the school environment is a part of their reality. If we evaluate and compare what is established by law with the educational results obtained by ADHD students, we must improve work directed towards ADHD people. We must meet their individual difficulties so that they have the same success and opportunities as the rest of the students (Cline, 2003; Moro-Ramos, 2021).

Addressing students with attention and concentration problems and impulse and movement control increases the difficulty in education (Tressoldi et al., 2012). Currently, numerous investigations are related to teaching core subjects aimed at ADHD students. However, there are few studies about strategies to work with these students and the teaching-learning of L2 (Moro-Ramos, 2021). In this sense, Liontou (2019) states, “limited research is available regarding the most beneficial teaching practices and materials for students with specific learning differences… in an EFL context” (p. 221). The need for methodological research is supported by Konicarova (2014), who figures that the ADHD child population “represents almost epidemic occurrence which needs to focus on research of special forms of education that are specifically different for various learning disciplines” (p. 62).

This research aims to grant all students the opportunity to learn English as L2 equally. This work begins by targeting ADHD students’ characteristics and types. Next, the learning difficulties and obstacles in learning L2 are exposed. Subsequently, educational adaptations are indicated, and different methods and strategies are explained.

2. ADHD

According to the American Psychiatric Association (2014), ADHD is “a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development” (p. 61). This pattern occurs in two or more settings (at school, home…). In addition, they negatively affect social, academic and/or work activities. Symptoms manifest before 12 years.

Attention deficit is manifested “by the lack of constancy in activities that require the participation of intellectual functions and by a tendency to change from one activity to another, without completing any, together with a disorganised, poorly regulated and excessive activity” (World Health Organization, 2009, p. 356).

Hyperactivity is due to excessive restlessness, which is reflected especially in situations that require calm. Mena Pujol (2011) defines ADHD as a neurobiological disorder “characterized by the presence of three typical symptoms: attention deficit, impulsivity and motor and/or vocal hyperactivity” (p. 1). Vaidya and Klein (2022) add, “with the last two symptom groups often clustered together” (p. 161). The lower number of neurotransmitters distinguishes an ADHD person’s brain, and differences in the frontal lobe and basal ganglia (Aguilar Millastre, 2014; Germano et al., 2010). This leads to a low ability to maintain attention and concentration and less control of behaviour (Aguilar Millastre, 2014; Hudson, 2017). On the other hand, genetics, education, and stimuli influence its appearance and development (Aguilar Millastre, 2014).

2.1. Characteristics of ADHD and intervention

According to Aguilar Milastre (2014), ADHD children have these symptoms: decreased attention compared to the attention of other children of the same age, overexertion or hyperactivity, and impulsivity or propensity to respond or act unexpectedly and/or without thinking.

It is easier to recognise ADHD students who have hyperactivity and impulsivity than those who show attention deficit (Hudson, 2017). ADHD students with combined subtypes are usually children with problems in writing and organising. They often have disputes with their peers due to teasing or provocation. In these individuals, depression becomes a repeated problem in personal and academic terms (Hudson, 2017).

The American Psychiatric Association (2014) describes the diagnostic criteria defining the pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity (see Table 1).

Table 1. DSM-5® Diagnostic Criteria

INATTENTION |

HYPERACTIVITY/IMPULSIVITY |

1. No attention to details or makes mistakes due to carelessness in schoolwork… |

1. Excessive body movements |

2. Difficulty maintaining attention on tasks or games |

2. Seat absence |

3. Not listening when spoken to directly |

3. Frequent runs or jumps |

4. Not following instructions and not finishing tasks |

4. Difficulty playing quietly |

5. Difficulty organizing tasks |

5. Being busy |

6. Refusal or avoidance of requiring sharp mental effort |

6. Excessive talk |

7. Loss of items needed necessary for tasks |

7. Impulsive answers even when the question is not completed |

8. Distractions due to external stimuli |

8. No turn-taking |

9. Carelessness of daily activities |

9. Frequent disruptions |

Source: American Psychiatric Association (2014, pp.59-60)

To confirm attention deficit and hyperactivity, and impulsivity, the child must manifest six or more of these symptoms, as well as maintain them for at least 6 months (American Psychiatric Association, 2014.). On the other hand, Millichap (2009) adds four more typologies: oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, mood disorder and anxiety disorder (see Table 2).

Table 2. Types of ADHD

No. |

Number |

Detection criteria |

1 |

Inattention without hyperactivity |

1. Careless mistakes 2. No attention keeping or listening 3. No task-finishing 4. Disorganization 5. Distraction |

2 |

Impulsive hyperactivity |

1. Nervousness 2. Seat absence 3. Continuous movement 4. Too much talk |

3 |

Inattention and impulsive hyperactivity |

It usually applies to children and adolescents whose symptoms have decreased with age or treatment |

4 |

Oppositional defiant disorder |

1. Temper loss 2. Discussion with adults 3. Refusal to do housework 4. Annoyance at other people 5. Frequent swearing |

5 |

Conduct disorder |

1. Lies 2. Absent play 3. Others´ property damage |

6 |

Mood disorder |

1. Increased self-esteem 2. Insomnia 3. Too much talk |

7 |

Anxiety disorder |

Shortness of breath, dizziness, heart rate fast, shaking, sweating, and choking |

Source: Millichap (2009)

Barkley (2011) asserts ADHD children may present other disorders such as dissocial, emotional, defiant negativism, and learning ones. These difficulties are more frequent in attention-deficit students. Combrinck and Preez (2021) conclude “Both sex and the language of learning and teaching are associated with ADHD and lower reading and numeracy achievement” (p. 67).

Other important aspects are low self-esteem and self-concept problems. ADHD children often change their mood and attitude, being unable to control emotions and frustration. Besides, because of the negative stimuli, these children often experience rejection feelings from people around. Similarly, the perception of being unable to do tasks adequately causes a negative self-concept. Once ADHD is diagnosed, it is necessary to make a correct intervention as soon as possible to avoid antisocial personality disorders and criminal behaviour (Aguilar Millastre, 2014). Besides, Teixeira Leffa et al. (2022) underline teachers’ role in the process because the demand at school “might reveal symptoms that are not present at home and because of their experience with children of similar age and development” (p. 7).

2.2. ADHD and Learning Issues

According to the National Joint Committee of Learning Disabilities (1994), the term Learning Difficulty refers to:

A heterogeneous group of disorders that are manifested by a significant difficulty in acquiring the rudiments of oral or written language, reasoning, or arithmetic, probably due to a dysfunction of the central nervous system that therefore occurs throughout the life cycle. (p. 65)

Most ADHD children have learning difficulties (Guzmán Rosquete & Hernández Valle, 2005). Academic performance is often lower than expected because of attention deficit, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (Mena Pujol, 2011; Kroese et al., 2000; Re & Cornoldi, 2013).

Learning in a formal context requires attention and self-regulation of mental processes. In repetitive tasks as school ones, ADHD students are impulsive, disorganized, and unable to maintain mental effort, so they end up failing (Barkley, 1998; Weiss et al., 1971). These children constantly stand and change from one activity to another without finishing any (Guzmán Rosquete & Hernández Valle, 2005). Not mastering literacy negatively influences the rest of learning, especially reading, writing and Maths (Guzmán Rosquete & Hernández Valle, 2005). Teixeira Leffa et al. (2022) explain the situation in this way,

Attention problems are usually more prominent when individuals with ADHD are assigned boring, tedious, or repetitive tasks… Moreover, inattention symptoms can increase while the patient is working on demanding tasks that challenge their cognitive processing abilities. Motivation, relevance, and attractiveness of the task for the child can influence the manifestation of symptoms. (p. 4)

Concerning reading, ADHD children perform omissions, additions and substitutions of words, syllables, and letters (/tr/ /bl/ /pr/ and /bl/), poor reading comprehension, and lack of motivation for both individual and group reading (inability to maintain attention on long tasks) (Mena Pujol, 2011).

When writing, ADHD children join and fragment words and add and omit letters; they repeat and replace syllables or words and tend to have more spelling mistakes. In addition, their calligraphy is poor and disorganised. As for mathematics, ADHD students have a poor understanding of statements, confuse signs, fail in calculations, and show difficulty abstracting high mathematical concepts far from reality (Mena Pujol, 2011).

On the other hand, ADHD is also associated with the cognitive area, mainly memory (limited capacity to assimilate information, difficulty remembering events...) (Aguilar Millastre, 2014; Guzmán Rosquete & Hernández Valle, 2005) and the perception of time (inability to organise and autonomous planning) (Aguilar Millastre, 2014).

3. Methodologies and techniques in the classroom

These must be short, concrete, and expressed positively to ensure students comply with instructions. A physical proximity between teacher and child is also needed. Equally, explanations must be motivating, dynamic and close to students’ reality. Tasks and duties should be brief, clear, and simple (Mena Pujol, 2011). Guzmán Rosquete y Hernández Valle (2005) propose the following indications when working with ADHD students (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Guidelines to work with ADHD students

Source: Adapted from (Guzmán Rosquete &Hernández Valle, 2005, p.13)

Hudson (2017) states that to help ADHD students, a teacher’s attitude (close, optimistic, and cheerful) and organised planning are essential. Classes should be structured (i.e., start with the same routine), be flexible in timing, provide time indications, use a multisensory approach to maintain students’ interest, use computers to improve their written work, and allow them to enjoy assignments. Hudson (2017) keeps students in rows facing the front, away from distractions, with space allowing movement.

Finally, since ADHD students often manifest behavioural difficulties causing complex situations to handle, we must know the techniques to face them. Mena Pujol (2011) proposes:

• Constant supervision: to foresee problematic situations (keep students’ self-control and security in tasks).

• Individualised tutorials of about ten minutes: used to indicate rules and limits.

• Positive reinforcement: when we want good behaviours to be repeated, we must use this technique to praise them (economy of the chips).

• Extinction: if we intend to reduce a negative behaviour we must stop attending to it (economy of the chips).

• Time out: when inappropriate behaviour occurs, students are isolated.

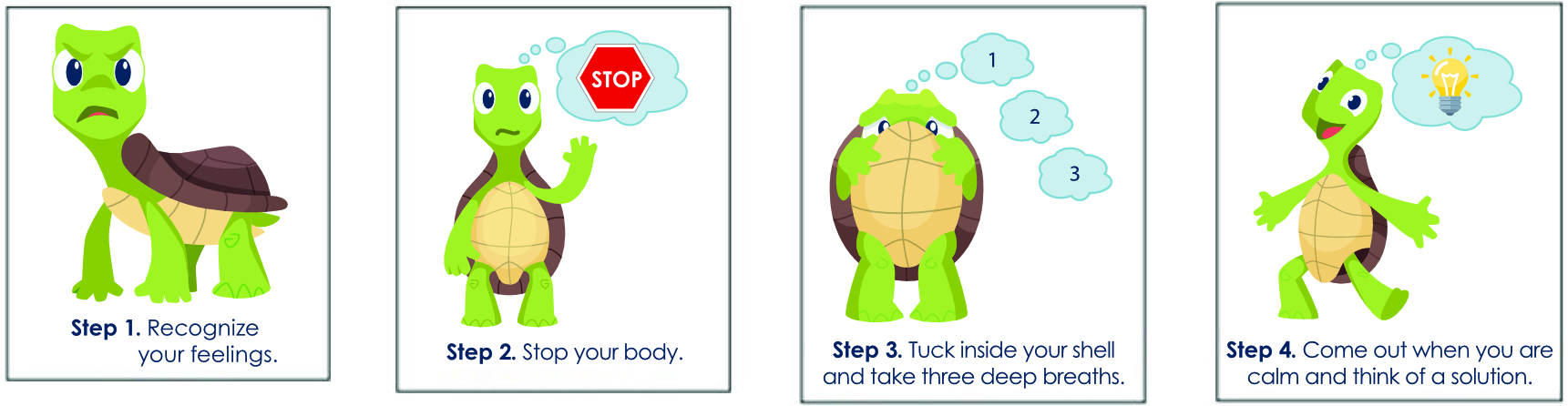

• Turtle technique: used to promote self-control and relaxation. The teacher tells a story so that ADHD students identify themselves with the protagonist. In stressful situations, the teacher pronounces the word turtle, and the child adopts a position imitating a turtle inside its shell (see Figure 2), which counts to ten (Mena Pujol, 2011).

• The traffic light: it allows students to self-register and self-evaluate. At the of the session, students self-evaluate using three colours. Each of them is associated with a behaviour: red indicates that the student is dissatisfied with his behaviour and that he will not repeat it; yellow reflects that the student is happy, but his behaviour can be improved; and green means the student is satisfied. This technique is also useful for working impulsivity (Pérez Cabello & Marzo Pavón, 2021).

Figure 2. Turtle techniques

Source: https://d66z.short.gy/Wu6vNl

Besides, Fundación CADAH (2012) offers strategies and methodological guidelines:

• The stopwatch of shame: different themes are used. Students roll some dice to advance on a board. According to the box, they speak on the subject for a minute without pauses.

• Cooperative or collaborative communication: its effectiveness depends on promoting group work, collaboration, reflective thinking, and action.

• Active listening: The basic guidelines are to look into the interlocutors’ eyes, maintain an open posture during the conversation, make gestures and sounds that indicate listening, and ask questions if we have not understood something. Students carry out an oral activity in which they evaluate themselves. The teacher may pose questions at the end of the activity to motivate attention.

• Non-verbal communication: the aim is to learn to recognise emotions in others, acquire knowledge about non-verbal communication, relate empathy with non-verbal communication, and extract information from others’ gestures.

• Motivation: tell them work is simple, offer them different activities and their purpose, establish a work schedule, and work the Pygmalion effect...

3.1. Obstacles in the process of learning a second language in ADHD students

Clares-Almagro (2013) states that to teach ADHD people, we must consider connections among pieces of information. In this way, it is essential to provide them with all the necessary information that allows their brain to establish connections (De la Cruz et al., 2020).

Navarro Romero (2010) distinguishes the understanding of language process acquisition in L1 and L2. He affirms there are common elements between both learnings. The process of teaching L1 is applied to the process of L2, although L1 acquisition is conducted unconsciously and influenced by biological factors (Klein, 1996).

ADHD students’ language difficulties appear when they acquire L1 (Tressoldi et al., 2012). In general, both speech inputs and outputs are altered. Many of them show difficulties in L1 linguistic competencies, problems that often creep into learning L2 (Sparks et al., 1992). Robinson (2003) states that attention plays an important role in acquiring L2. Attention is related to short-term memory and working memory.

In the classroom, ADHD students receive a large amount of information, which can create chaos in their brains. Their sensory receptors are continuously working. They also have difficulty processing and distinguishing important information. Likewise, its language acquisition mechanism (Chomsky, 2000) is also altered due to the limitations of its ability to discriminate phonemes (Turketi, 2010).

Listening comprehension problems are noticeable among ADHD students. Although interested, they only focus on some attractive details without grasping the main ideas (Mapou, 2009; Turketi, 2010). We must attractively present input, reinforce it several times, and use different channels (audio, visual…) (Kuczula & Lengel, 2010; Turketi, 2010).

Stokman (2009) notes, “the acquisition of complex human skills, including language, is undoubtedly a multisensory task, involving the collaboration of all the senses” (p. 12). The more connections made and stimuli received, the more ADHD students learn. To become familiar with a new word, children must listen to it, see its spelling and picture, see, and touch the object denoted, and understand its function in a sentence or a close actual situation (Turketi, 2010). Turketi (2010) provides these suggestions (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Suggestions to work with ADHD students

Source: (Turketi, 2010, p.7)

L2 writing skills are less automatic, so they affect working memory more. ADHD students usually make more spelling mistakes than in L1 since it is challenging to organise, plan and correct their writing (Kałdonek‐Crnjaković, 2020). Turketi (2010) details that writing is one of the biggest challenges in learning L2. Many students end up writing in the same way they listen or read. When it comes to reading in L2, as in L1, ADHD students have problems skipping letters, words and even lines. In addition, they often confuse similar characters or their order. They often misunderstand content and have difficulty understanding polysemic words. ADHD children are usually slow readers due to poor decoding capacity, specifically with some English characters (b, d, p, q).

Regarding outputs, Turketi (2010) declares that they encounter difficulties in speaking and writing both in L1 and L2. The main problems are experienced at the syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic level (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Language output problems of ADHD students

Source: (Turketi, 2010, p.11)

ADHD children’s output problems are due to difficulties generated by poor inputs (Turketi, 2010). In turn, the problems derived from hyperactivity and impulsivity impact oral interaction and production. As ADHD individuals are unable to control their behaviour voluntarily, they may present problems in developing sociopragmatic aspects of oral skills required effectively.

Evaluation in ADHD students requires both time and format adaptations (providing more time, granting breaks during the exam, or allowing them to use technologies) (Hudson, 2017).

3.2. Methods and intervention strategies for the teaching of English as L2 to ADHD students

ESL methodology diversity let us apply different techniques in teaching ADHD children. The challenge lies in choosing efficient means (Turketi, 2010). Teaching SEN students and AICLE students share some characteristics: task-based oriented, communicative purpose, interaction and evaluation techniques, activities difficulty gradation, and dynamic groupings (Pérez-Cabello & Marzo-Pavón, 2021).

Considering the difficulties of ADHD students, Turketi (2010) highlights the following methods: TPR (Total Physical Response), The Silent Way (TSW) and Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT). A flexible combination of the different methods would fulfil these children’s needs.

3.2.1. TPR

TPR is developed by Asher (1977). He believes the fastest and least stressful way to understand L2 is to follow the teacher’s instructions without using L1 (Larsen-Freeman & Anderson, 2011). To reduce stressors, the learning of L2 is based on how children learn L1.

In L1, communication between parents and children consists predominantly of commands to which the child responds physically before beginning to respond verbally (Richards & Rodgers, 2014). Konicarova (2014) describes TPR central processes so:

The first is based on developing listening competence… In the second period the ability of listening comprehension is linked to physical response to spoken language which enables to create cognitive maps. In the third period, the learning is focused on spontaneous speech production (p. 65).

TPR brings many advantages in teaching L2 to ADHD students. Physical activities address these children´s need for movement and reduce stressors and affective filters. It helps ADHD students experience success in learning L2. At the same time, they focus on action. They focus on learning objectives (Turketi, 2010, p. 24).

Turketi (2010) states that it has great benefits for ADHD students. It allows them to remember linguistic material in the long term since associating a word with some physical movement provides additional connections in their brain. ADHD students find it easier to perceive grammatical structures and internalise them intuitively.

The TPR method contributes to enjoyable and satisfying learning. However, abusing it can cause tiredness. Thus, combining it with other language teaching methods encourages ADHD students’ progress in their acquisition of L2.

3.2.2. TSW

It was developed by Gattegno (1972) as an educational theory based on the cognitive principles of the learning process. Silence and gestures are used as teaching tools to focus students’ attention, elicit responses, and encourage them to correct their own mistakes (Larsen-Freeman & Anderson, 2011).

It is based on visual and experiential learning. Students begin studying phonemes with a colour chart. Based on L1 phonemes, the teacher leads students to associate L2 phonemes with certain colours. Subsequently, these colours help children learn the corresponding spelling and read and pronounce words correctly (Larsen-Freeman & Anderson, 2011). To learn grammar and vocabulary tangibly, students manipulate coloured sticks. This is essential for ADHD students since they can see and touch language. However, care must be taken not to give students too many coloured sticks at once. This can provoke inattention.

TSW allows grammar to be learnt inductively. Students must figure out grammar by producing grammatically similar structures. This method stimulates self-correction and self-awareness, essential skills in the learning process that most ADHD students lack (Turketi, 2010).

It should be combined with other approaches to avoid overuse. Abuse of concentration and attention can be exhausting and frustrating for ADHD students. TSW usually works well when teaching grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation in artificial linguistic situations. However, to develop and promote a more natural communication in L2 we can use TBLT.

3.2.3. TBLT

TBLT is based on the acquisition of L2 because of an intentional non-linguistic activity (a task). In this way, acquired language knowledge is the product of real and meaningful communication. Tasks are the main elements of this method. Learning by doing or experiential learning of this approach allows students to commit to objective achievements (Turketi, 2010; Yousefzadeh, 2016).

For ADHD students, TBLT is more useful and beneficial than traditional language instruction. It allows them to stay focused and involved in the task. The teacher strategically places students in a situation of need in which they must learn words, sentences, or grammar to execute the proposed task. This generates ADHD students’ brains focus on an objective that is not linguistic (Turketi, 2010).

It involves students’ active participation. Meanwhile, the teacher supervises students’ performance and intervenes when necessary. The task must have precise results so that both students and teachers can know if it has been completed successfully. After that, a reflection phase is fulfilled to reinforce students’ learning problems (Larsen-Freeman & Anderson, 2011). Questions such as: What was difficult for you in this task? What was the easiest? What did you learn from it? help children to analyse their learning strategies and reflect on how they can improve them (Turketi, 2010).

Space organisation in this method is important. Groups should be placed apart to decrease interference from each other’s activities. ADHD students should sit in front of the classroom and close to the teacher to avoid possible distractions (Turketi, 2010). TBLT characteristics and the other methods presented allow teaching L2 to ADHD students in a motivating and innovative way.

Konicarova (2014) adds the Communicative Language Teaching (CLT). It focuses on functional structures and social interaction activities (Richards & Rodgers, 2014).

3.3. Intervention strategies for English lessons

Moro-Ramos (2021) ponders learning difficulties ADHS students may present when developing the four basic language skills (reading, writing, listening and oral production) (see Table 3).

Table 3. Intervention strategies in the area of English aimed at students with ADHD.

Reading problems |

- Make reading comprehension cards appropriate to the level - Get students used to looking up the dictionary - Search for motivational texts - Follow reading with a pencil or pointer so they don’t get lost - Practice skimming and scanning activities - Ask questions to ensure they understand the texts - Make games with acronyms, metaphors, and oxymorons |

Writing problems |

- Propose crossword puzzles, stairs (acronym game) unscramble and other word games - Play hangman - Name pictograms - Use computer to write - Respect ADHD students’ learning pace - Practice the self-instruction scheme for written activities. (read > think > answer > ask for help if needed > review > check) |

Problems in listening comprehension |

- Repeat oral productions until children understand them - Use visual aids and gestures - Give simple short instructions - Create gestures of complicity with ADHD students to ensure they understand the message - Vary the tone of voice - Use Sandwich Technique (L2-L1-L2) when necessary - Tell anecdotes or use a sense of humour to keep students’ attention - Create mental images of the messages - Practice the self-instruction scheme for oral activities. (Listen > Nod if you understand > ask if you don’t) |

Problems in oral production |

- Encourage students to express themselves in English - Allow them to insert L1 words when they are not able to deliver the full message in English and provide them with the words of that language they lack - Give them time to respond and elaborate the message, transmitting calm - Reward correct behaviour (for example, not respecting speaking turns or not interrupting). - Provide Feedback (praise progress and correct mistakes positively) |

Source: Based on (Moro-Ramos, 2021, pp. 11-15)

De la Cruz et al. (2020) detail teaching-learning strategies to work with ADHD students in English lessons (see Table 4).

Table 4. Teaching-learning strategies for students with ADHD.

No. |

Strategy |

Objective |

Technique |

1 |

Learning without fear |

Provide ADHD children with security during the teaching-learning process. |

Post lesson plan and class rules in a visible place. |

2 |

Organize time |

Help ADHD children correctly manage time according to tasks. |

Include a clock and distribute tasks, topics, and subtopics according to time. |

3 |

Visualize work |

Take advantage of the good visual ability of ADHD children. |

Assignments and lessons must be presented in an attractive way. |

4 |

Learning by playing |

Teach English in a fun way that stimulates their desire to learn. |

We must counteract lack of attention and hyperactivity. We can propose games to capture their attention and promote their need for movement. |

5 |

Evaluation of learning |

Direct students in a simple way about what to do. |

Questions should be short, clear, and simple. Complete not very extensive colourful worksheets, mostly illustrated and with short questions. |

Source: Based on (De la Cruz et al., 2020; Clares-Almagro, 2013)

4. Research methodology

This work is the result of a mixed methodology. That is, qualitative and quantitative aspects are fundamental pillars of developing this methodological design, which also puts much of the theoretical content into practice. In this way, it is intended to build global and joint planning.

This research begins with a qualitative study. This allows us to know ADHD students’ needs when learning English and identify strategies and methods that facilitate teaching that language. The collection of information is performed following the documentary research technique. Different books and articles related to ADHD students’ difficulties in learning L1 and L2 and works related to methods and strategies in English were examined. Besides, an open question in the questionnaire provides us with qualitative data.

After this, a qualitative methodology applies to compare the previous results based on existing theories and hypotheses and, thus, be able to offer truthful conclusions. An anonymous survey was designed for English teachers in primary education, early childhood education, and high school to check how they adapt the teaching of English to ADHD students. Eleven responses have been obtained from 8 centres in Condado de Huelva (6 public schools and two granted ones). Eight of the teachers are women, and three are men. The ages are between 38 and 54 years. Thanks to the respondents, we have been able to analyse actual data. The survey consists of eleven questions -ten are closed and one open, so respondents could freely express themselves about the subject.

5. Results

Most teachers teach in Primary Education (63.6%, 7 p.) and the rest in Early Childhood Education (36.4%, 4 p.). 42.9% of Primary School instructors teach in the second cycle. This percentage is followed by teachers in the first cycle (28.6%). Finally, 14.3% work in the first and second cycles and the same amount in the third cycle.

Regarding the presence of ADHD students in the English language classroom, all teachers claim to have ever had ADHD students. 90.9% (10 p.) indicate their students had ADHD or a combined subtype. 100% adapt lessons for ADHD students.

As methods, the most selected are TPR (100%, 11 p.) and CLT ((100%, 11 p.). These are followed by TBLT (45.5% 5 p.), Universal Design for Learning (UDL) (18.2%, 2 p.) and Multisensory Structures Learning (MSL) (9.1%, 1 p). None of the respondents apply The Silent Way and Content-Based.

The adaptation modes selected by all are: Placing students near the teacher and placing them among classmates who serve as a model, Proposing meaningful activities, and Providing visual aids (100%, 11 p.). 10.9% (10 p.) choose Organising and adapting the classroom space, Creating different material, and Adapting the curriculum to students’ needs.

These replies are followed by Having a support teacher (81.8%, 9 p.), Coordinating with Therapeutic Pedagogy teacher (63.6%, 7 p.), Eliminating stimuli outside their visual field (36.4%, 4 p.), Enhancing cooperative learning (27.3%, 3 p.), and Proposing breaks every 20 minutes (18.2%, 2 p.).

Difficulties discussed are Problems in oral comprehension and Slowness in the processing of spoken and written language (100%). 90.9% (10 p.) add that these students have Problems in oral production and 81.8% (9 p.) indicate they manifest Difficulties in following the rules of sentence construction when speaking and writing.

In addition, 72.7% (8 p.) specify ADHD children show Difficulty in writing. 45.5% (5 p.) speak of Written work with spelling errors, incoherent at the sentence/paragraph level and inconsistent concerning spelling, vocabulary, and punctuation use. Finally, the least selected options are They write the same way they listen (27.3%, 3 p.) and Reading problems (skipping letters/words/lines, confusing characters such as “b”, “d”, “p”, “q”, among others) (9.1%). None of the participants selected incorrect use of words due to misunderstanding of their meanings.

About the intervention strategies 100% (11 p.) use or would use Visualise work (attractive, interactive tasks, among others) and Use visual supports and gestures. 90.9% (10 p.) select Organize time and Learn by playing. The least indicated options are Use self-instruction schemes for written and oral activities (36.4%, 4 p.), Allow them to use L1 and L2 and Use computer to write, both with 27.3% (3 p.). 9.1% (1 p.) select Use pictograms.

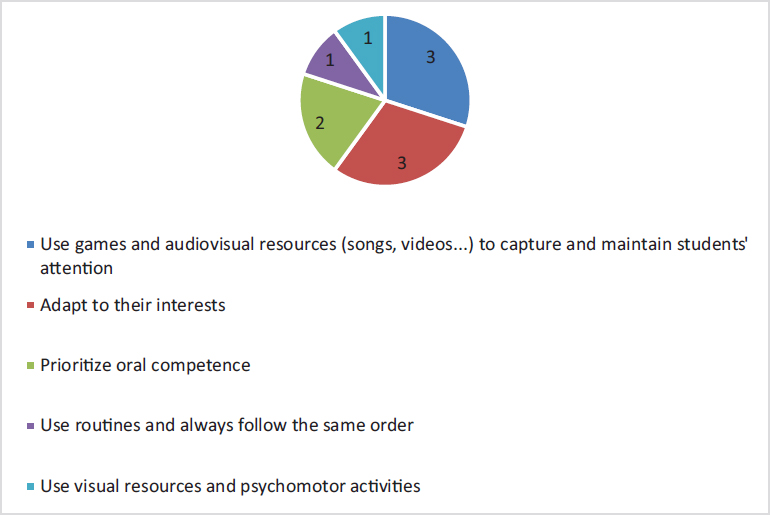

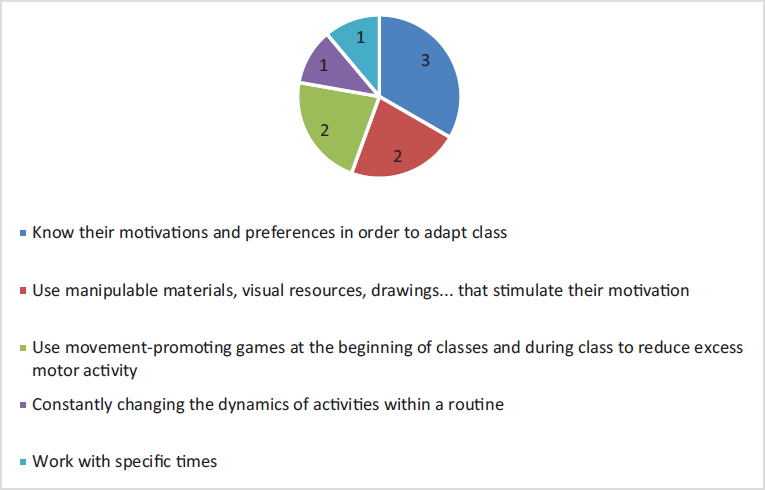

Finally, recommendations for teaching English to ADHD students are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 5. Infant teachers’ recommendations

Figure 6. Primary teachers´ recommendations

6. Discussion

This research verifies one child in each classroom may suffer from ADHD. All teachers surveyed claim to have ever had ADHD students. In the same way, it has been corroborated that ADHD is the most frequent disorder in students.

On the other hand, all teachers surveyed claim to adapt their teaching to ADHD children favourably. These data do not correspond to the studies presented above. Teachers highlight the difficulty in schools adapting English teaching for these students. The results obtained are astonishing and, at the same time, disappointing since the evidence was expected to exemplify the absence or poor adaptation existing in many centres.

Regarding adaptation data, most teachers use those indicated by Guzmán and Hernández (2005), Hudson (2017), and Guerrero (2016). Teachers place ADHD students near them and among peers who serve as role models and support. They also propose meaningful activities to encourage students’ active participation and use visual aids to facilitate organisation. Teachers adapt and organise the classroom to students’ movement needs (Guerrero, 2016). Guerrero (2016) and Guzmán and Hernández (2005) support frequent brain breaks. Entertainment tasks are the least selected, thus questioning the usefulness of maintaining students’ motivation. Few teachers select cooperative learning.

On the other hand, different material creation, curriculum adaptation to students’ needs, a support teacher and coordination with a Therapeutic Pedagogy teacher are measures present in teachers’ replies.

According to the results, the most common problems are oral comprehension and slow processing of spoken and written language (Turketi, 2010). This generates problems in ADHD students’ oral production, as said by most respondents.

Data also reveal that ADHD students often struggle with sentence construction rules when speaking and writing (Turketi, 2010). Kałdonek‐Crnjaković (2020) states that ADHD students can also present difficulties with written work. Results support this aspect. Most teachers indicate that ADHD students have problems in organising, planning, and correcting. As specified by Kałdonek‐Crnjaković (2018), ADHD students’ written works show spelling errors, inconsistency at the sentence/paragraph level, vocabulary, and punctuation. Although Turketi (2010) comments that ADHD students usually write the same way they listen or read, few participating teachers corroborate this difficulty. Likewise, only one teacher exposes reading problems (letters/words/lines are skipped, characters such as b, d, p, q, mainly).

Concerning intervention strategies, most develop attractive and interactive tasks and use visual supports and gestures. These strategies verify Turketi’s study (2010). He argues that interactive and visual activities requiring creativity, commitment, and movement promote ADHD students’ concentration and productivity in their learning.

Time organisation, together with learning, are the most selected options. These strategies are ideal and fulfil ADHD students’ academic needs. In addition, they help these students to show a greater predisposition in the learning process (Clares-Almagro, 2013).

Some respondents also use computers to help students improve their written work (Hudson, 2017). Only one respondent uses pictograms, and few allow students to speak while mixing L1 and L2.

Similarly, Moro-Ramos (2021) indicates that TPR activities are attractive for all students, especially for ADHD ones. He also defends that they can reduce stress in learning due to the playful component and the possibility of movements.

Concerning methods, all teachers choose the CLT. This method is used by De la Cruz et al. (2020) to detect methodological strategies for teaching English to ADHD young people. All teachers also select TPR. To some extent, the data obtained coincides with Turketi (2010). The first is justified because it addresses the needs of the students’ movement. The second promotes students’ active participation. However, Turketi (2010) also includes the so-called TSW. This method is not selected. Thus, the usefulness and benefits for ADHD children are questioned.

The other two methods chosen are MSL and UDL. Kałdonek‐Crnjaković (2018) advocates for the first because it is based on the simultaneous input channels: visual, auditory, kinesthetics, and tactile. Designing activities involving all senses will keep ADHD students occupied and more focused. As for UDL, the Fundación CADAH (2012) promotes its implementation to achieve inclusion in all subjects. However, only 2 respondents used it. This seems to be paradoxical since most of the participants adapt their lessons.

Several teachers stress establishing predictable routines. In this way, students will feel more secure and can perform tasks correctly and autonomously. These recommendations are consistent with Clares-Almagro (2013). Another aspect mentioned is to know students’ interests, motivations, preferences and learning styles. Thus, adapting lessons optimally and keeping them motivated will be possible. Likewise, they stress other methodological resources such as drawings, manipulable materials, and audio-visuals. Guerrero (2016) coincides with these strategies.

The most recommended recommendations are to develop attractive and interactive lessons that teach by doing (Clares-Almagro, 2013). Some underline the importance of the second to address hyperactivity, while others use it to reduce students’ energy and get them to perform other activities. The implementation of this strategy is, in turn, consistent with Guerrero (2016). Finally, it is worth highlighting the recommendations of prioritising oral over written skills and designing communicative activities.

7. Conclusions

The main objective of this study is to investigate didactic strategies and methods for teaching English as L2 to ADHD students. This objective has been met. Research and analysis have been conducted on the strategies and methods proposed by different authors, contrasting them with those currently used in 8 schools in Condado de Huelva. To reach this point, learning characteristics and difficulties have been examined, and the obstacles for ADHD students have been identified.

The results allow us to conclude that the strategies are mainly learning by playing, organising time, visualising work and using visual supports and gestures. They are applied thanks to TPR, TBL, and CLT. However, given that educational practice is very diverse, as well as the characteristics and needs of each student, teachers must vary their methods and strategies according to the particularities of the classroom, each student, and each moment. To consider ADHD students’ individual characteristics, it is first essential to detect their interests, tastes, strengths, and motivations. When proposing attraction and movement, we must remember that time management is essential since attention dissipates during the development of prolonged activities. The data obtained and those consulted coincide in using a visible clock in the classroom, audio-visual resources, and the anticipation of schoolwork strategies to facilitate students’ organisation in their learning process.

This study presents limitations. Among them, the sample size could be expanded, and the study could be extended. Likewise, the data collected are restrictive because they are mainly derived from closed answers. This could be corrected through interviews and qualitative data collection.

Finally, it should be noted that ADHD should not be conceived as a disease but as an individual characteristic some students possess. It can be controlled and attenuated by the people in the environment. The self-esteem problems these children may present contribute to the fact that they do not reach the planned objectives and do not have the same opportunities as their peers. The right strategies can encourage social interaction in L2, which would give them confidence and security.

Authors’ contribution

Ana Mª Pérez-Cabello: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Research, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - review and editing.

Margarita Gil-Pérez: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Research, Methodology, Software, Writing - original draft.

Francisco Jesús Oliva-Pérez: Research, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing - review and editing.

References

Aguilar Millastre, C. (2014). TDAH y dificultades del aprendizaje: Guía para padres y educadores. Diálogo.

American Psychiatric Association (2014). Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales (DSM-5®). Médica Panamericana.

Asher, J. (1977). Learning Another Language Through Actions: The Complete Teacher’s Guidebook. Sky Oaks Productions.

Barkley, R. A. (1998). Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. A Handbook for diagnosis and treatment. Guilford Press.

Barkley, R. A. (2011). Niños hiperactivos: cómo comprender y atender sus necesidades especiales: guía completa del trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad (TDAH). Paidós.

Chomsky, N. (2000). New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind. Cambridge University Press.

Clares-Almagro, M. (2013). TDAH y el aprendizaje de inglés en la escuela: Una propuesta metodológica [Final Degre Project, International University of la Rioja].

Cline, T. (2003). The Assessment of Special Educational Needs for Bilingual Children. BJSE, 25(4), 159-163. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8527.t01-1-00079

Combrinck, C. & Preez, H. (2021). Validation of the ADHD-Behaviour Rating Scale for early childhood teacher use in South African classrooms. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 31(1), 61–68, https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2020.1871249

De la Cruz, G., Ullauri-Moreno, M. I., & Freire, J. (2020). Estrategias didácticas para la enseñanza de inglés como lengua extranjera (EFL) dirigidas a estudiantes con trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH). Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 22(2), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.16118

Fundación CADAH. (2012). TDAH. Fundación CADAH. https://d66z.short.gy/51hcAP

Gattegno, C. (1972). Teaching Foreign Languages in Schools: The Silent Way. Educational Solutions.

Germano, E., Gagliano, A., & Curatolo, P. (2010). Comorbidity of ADHD and dyslexia. Developmental Neuropsychology, 35(5), 475-493. https://doi.org/10.1080/87565641.2010.494748

Guerrero, R. (2016). Trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad. Planeta.

Guzmán Rosquete, R., & Hernández Valle, I. (2005). Estrategias para evaluar e intervenir en las dificultades de aprendizaje académicas en el Trastorno de Déficit de Atención con/sin Hiperactividad. Revista Qurriculum, 18, 147-174.

Hudson, D. (2017). Dificultades específicas de aprendizaje y otros trastornos: Guía básica para docentes. Narcea.

Kałdonek‐Crnjaković, A. (2018). The cognitive effects of ADHD on learning an additional language. Govor, 34(2), 215-227. https://doi.org/10.22210/govor.2018.35.12

Kałdonek‐Crnjaković, A. (2020). Teaching an FL to students with ADHD. Govor, 7(2), 205-217. https://doi.org/10.22210/govor.2020.37.10

Klein, W. (1996). Language Acquisition at different ages. In D. Magnusson (Ed.), Individual Development over the Lifespan: Biological and Psychosocial Perspectives (pp. 88-108). Cambridge University Press.

Konicarova, J. (2014). Psychological Principles of Learning Language in Children with ADHD and Dyslexia. Activitas Nervosa Superior, 56(3), 62-68. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03379610

Kroese, J. M., Hynd, G. W., Knight, D. F., Hiemenz, J. R., & Hall, J. (2000). Clinical appraisal of spelling ability and its relationship to phonemic awareness (blending, segmenting, elision, and reversal) phonological memory, and reading in reading disabled, ADHD, and normal children. Reading and Writing, 13, 105–131. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008042109851

Kuczala, M., & Lengel, T. (2010). The Kinesthetic Classroom: Teaching and Learning through Movement. Corwin.

Larsen-Freeman, D., & Anderson M. (2011). Techniques and Principles in Language Teaching. Oxford.

Liontou, T. (2019). Foreign language learning for children with ADHD: evidence from a technology-enhanced learning environment. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 34(2), 220–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2019.1581403

Mapou, R. L. (2009). Adult Learning Disabilities and ADHD: Research-informed Assessment, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195371789.001.0001

Mena Pujol, B. (2011). El alumno con TDAH: Trastorno por Déficit de Atención con o sin Hiperactividad. Adana.

Millichap, J. (2009). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder handbook: A physician’s guide to ADHD. Springer Science & Business Media.

Moro-Ramos, S. (2021). Estrategias de intervención educativa en el área de inglés en educación primaria para estudiantes con trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad. Revista Electrónica Educare, 25(3), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.25-3.20

National Joint Committee of Learning Disabilities. (1994). Collective perspectives on issues affecting learning disabilities. PROED.

Navarro Romero, B. (2010). Adquisición de la primera y segunda lengua en aprendientes en dad Infantil y Adulta. Philologica Urcitana, 2, 115–128.

Pelaz, A., & Autet, A. (2015). Epidemiología, diagnóstico, tratamiento e impacto del trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad. Revista española de Pediatría, 71(2), 57-61.

Pérez Cabello. A. M., & Marzo Pavón, A. (2021). El alumno con Necesidades educativas especiales NEAE y la lengua extranjera. In M. Saracho-Arnáiz, & H. Otero-Doval (Eds.), Internacionalización y enseñanza del español como lengua extranjera: plurilingüismo y comunicación intercultural (pp. 1046-1070). ASELE.

Re, A. M., & Cornoldi, C. (2013). Spelling errors in text copying by children with dyslexia and ADHD symptoms. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 48(1), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219413491287

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2014). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Robinson, P. (2003). Attention and memory in SLA. In C. Doughty, & M. Long (Eds.), The Handbook of Second Language Acquisition (pp. 631-678). Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470756492

Sparks, R., Ganschow, L., Pohlman, J., Skinner, S., & Artzer, M. (1992). The effect of multisensory structured language instruction on native language and foreign language aptitude skills of at-risk high school foreign language learners, Annals of Dyslexia, 42(1), 25-53. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02654937

Stockman, I. J. (2009). Movement and Action in Learning and Development: Clinical Implications for Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Academic Press.

Teixeira Leffa, D., Caye, A., & Rohde, L. A. (2022). ADHD in Children and Adults: Diagnosisand Prognosis. In S.C. Stanford, & E. Sciberras, (Eds.) New Discoveries in the Behavioral Neuroscience of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences (pp. 2-18). Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2022_334

Tressoldi, P. E., Cornoldi, C., & Re, A.M. (2012). Batteria per la valutazione della scrittura e della competenza ortografica nella scuola dell’obbligo. Organizzazioni Speciali.

Turketi, N. (2010). Teaching English to Children with ADHD. MA TESOL Collection. 483.

Vaidya, C. J., & Klein, C. (2022). Comorbidity of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorders: Current Status and Promising Directions. In S.C. Stanford, & E. Sciberras, (Eds.) New Discoveries in the Behavioral Neuroscience of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences (pp. 159-177). Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2022_334

Weiss, G., Minde, K., Werry, J., Douglas, V., & Nemeth, E. (1971). Studies on the hyperactive child, VIII. Five year follow-up. Archives of General Psychiatry, 24, 409-414. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1971.01750110021004

World Health Organization. (2009). ICD-10 2008: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems. 10th Revision. World Health Organization.

Yousefzadeh, M. (2016). The Effect of Task Based Language Teaching on Disabled Learners´ First Language Written Task Accuracy, Fluency, and Complexity. International Journal of Educational Investigations, 3(5), 52-60.

_______________________________

(*) Autor de correspondencia / Corresponding author

1 See Germano et al. (2010).