SITIO WEB: https://revistas.usal.es/index.php/1130-3743/index

Education at the heart of the humanities[1]

La educación en el corazón de las humanidades

Chris HIGGINS

Boston College. EE. UU.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2443-0369

Date received: 03/03/2021

Date accepted: 01/08/2021

Date of publication on line: 01/01/2022

How to cite this article: Higgins, Ch. (2022). Education at the Heart of the Humanities. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 34(1), 49-68. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.25970

ABSTRACT

As schools of education are currently organized, philosophers of education lead a marginal and furtive existence. As education comes more and more to be understood as social scientific research into «what works» in the schools, philosophers seem like a poor lot indeed. Even our role in teacher education, once secured by the metaphor of foundations, is now questionable. Debates in teacher education are lively enough: Do teachers need more coursework or more clinical experience? And if they need more coursework, do they need more classes in curriculum and instruction or more background in their «content area»? Notice, though, that the kind of experience educational philosophers are best suited to provide for teachers is not even in the picture. What is this experience? In a word, it is liberal learning about and for education. If education is a space of humanistic questions, philosophy a love of these questions in their openness, and educational philosophy the craft of keeping alive the texts and conversation that helps us re-open such questions, then philosophical teacher education is an invitation to teachers to be humane intellectuals of their field. It is an invitation to join a conversation of millennial interest. Under the conception I have advanced, educational philosophy is far from marginal. It stands to remind how each positive program of research into what works begs key questions. And it stands to remind the university that, to paraphrase the famous essay by Sartre, education is a humanism. When education and the humanities are reconnected their place at the center of the university becomes clear.

Key words: Philosophy of Education; humanism; University; teacher education; Pedagogy.

RESUMEN

Tal y como están las facultades de educación organizadas actualmente, los filósofos de la educación tienen una existencia marginal y furtiva. A medida que la educación se entiende cada vez más como una investigación científica social sobre «lo que funciona» en las escuelas, los filósofos parecen ser cada vez más inútiles. Incluso nuestro papel en la formación del profesorado, que una vez estuvo asegurado por la metáfora de los fundamentos, ahora es cuestionable. Los debates en la formación del profesorado están bastante animados: ¿los profesores necesitan más asignaturas o más experiencia clínica? Y si necesitan más asignaturas, ¿necesitan más clases de didáctica o más conocimiento sobre la asignatura que enseñan? Nos damos cuenta así de que el tipo de experiencia que los filósofos de la educación pueden ofrecer a los profesores ni siquiera está en el marco de interés. ¿Cuál es la experiencia que los filósofos de la educación podemos ofrecer? En una palabra, es un aprendizaje liberal acerca de y para la educación. Si la educación es un espacio de preguntas humanísticas, la filosofía un amor por estas preguntas en su apertura y la filosofía educativa el oficio de mantener vivos los textos y la conversación que nos ayudan a reabrir tales preguntas, entonces la formación filosófica del profesorado es una invitación a los profesores a que sean intelectuales humanos de su campo. Es una invitación a unirse a una conversación de interés milenario. Según la concepción que he desarrollado, la Filosofía de la Educación está lejos de ser marginal. Nos ayuda a recordar cómo cada programa educativo sobre «lo que funciona» plantea preguntas clave. Y, además, recuerda a la universidad que, parafraseando el famoso ensayo de Sartre, la educación es un humanismo. Cuando la educación y las humanidades se vuelven a conectar su lugar en el centro de la universidad queda claro.

Palabras clave: Filosofía de la Educación; humanismo; universidad; formación del profesorado; Pedagogía.

1. Introduction

There are two ways to draw up the history of educational philosophy in the West. In one version, the field ends up about 50-100 years old; in the other, it has been around for millennia. In this paper, I want to explore this latter, longer history, not because it sounds more noble and grand, but because I am convinced that the modern, institutional origin story saddles us with assumptions that narrow and obscure what educational philosophy can be.

Philosophy long predates its professionalization and educational philosophy is as old as philosophy itself, with questions about the nature of learning and teaching occupying a central place in the work of founding figures like Plato. The point here is not to show that we have a long history of applying philosophy to education, but rather that no application was deemed necessary until very recently in intellectual history. For more than two millennia after Plato, educational questions remained central to philosophical inquiry in the West. For thinkers as diverse as Cicero, Augustine, Boethius, Aquinas, Erasmus, Vico, Rousseau, Schiller, and Oakeshott, education was not an extraneous topic calling for philosophical afterthoughts, but the very ground of their most important philosophical inquiries. Until recently, it has seemed natural for philosophers to take up questions about knowledge by examining how we come to know; to consider questions about the good life by investigating how one becomes virtuous; to approach the nature of the ideal society through a discussion of how to educate future citizens; and to contemplate human nature by asking what it means about us that teaching and learning are such a fundamental aspects of the human condition.

However, by the time philosophy joins the ranks of formalized, academic disciplines at the end of the nineteenth century, it has undergone a series of significant transformations. It has abandoned its traditional task of articulating and exemplifying a way of life that can guide human conduct in favor of constructing systematic theories (Hadot, 1995). Further, it has ceded to the newly emerging social sciences its traditional concern with the developing person and with social practices such as education. Thus, when philosophy and education are reunited in the modern discipline of Philosophy of Education, it is in a doubly alienated way. As an applied subfield, Philosophy of Education is thought to stand at a remove from «pure» philosophy, which in turn is thought to stand at a remove from the practical and the everyday.

In what follows, I will attempt to remove this kink in the logic of our self-understanding and offer what I believe to be a more fruitful way of understanding philosophy, education, and their relation, that I hope will prove useful for thinking about the importance of educational philosophy in educational research and the preparation of teachers.

2. Philosophy as a love of open questions

Philosophy has come to be associated with a set of questions and with the texts that pose these questions explicitly, but I would argue that both of these characterizations miss what is essential and unique about philosophy. There is something dishonest about retrospectively identifying philosophy with a set of questions and the famous attempts to answer them. To do so makes it seem as if the questions were there already. Although there is some truth to Whitehead’s famous comment that all Western philosophy is a footnote to Plato, the history of philosophy, in the making, was a history of the discovery of new questions. Philosophy, like (modern) art, is an essentially frame-breaking activity. Questions such as ‘What does the human subject contribute through categories and intuitions to the structuring of the world?’ or ‘How are power relations written into our very experience of embodiment?’ now strike us as typically philosophical, but this is only because Kant and Foucault taught us how to ask them. They provoked us to see all that had come before in a new light, revealing questions that previously had been obscured.

Thus, we should not define philosophy by the type of questions asked. The modern domain of philosophical questions is simply that which was not taken over by other disciplines. Philosophy is the discipline that takes on the questions that seem too big, too normative, or to stubbornly non-empirical for other disciplines. But there is also an older and broader sense of philosophy captured in the name ‘Doctor of Philosophy’. One can receive a Ph.D in philosophy of course, but also in botany or Slavic languages and literatures. The word philosophy is present in every graduate degree not because every dissertation raises philosophical questions in the modern sense, but because there is, or was, an essential connection between philosophy and learning in general. One cannot claim maturity as a scholar, the idea is, unless one has both mastered the particular methods and canon of one’s specific field and also learned how to relate those particulars to the broad circle of knowledge and to the human situation. Without this broader perspective, the scholar cannot gain an external perspective on his or her field, will be unable to recognize, for example, whether it has become obsessed with trivialities or devolved into arid formalism, and thus cannot truly be said to know his field.

As it is customary to note, this older sense of philosophy is visible in its etymology, from philia (love, friendship) and sophia (wisdom). Even knowing the problems of etymological arguments, perhaps this could help us combat the narrowing of philosophy in this era of scholarly specialization and professionalization—while searching for fresh language to bring the point home. ‘There are nowadays professors of philosophy, but not philosophers’, Thoreau once quipped, and while this is overstated for emphasis, it contains a kernel of truth (Thoreau, 1986/1854, p. 57). This is a good start, interrupting our tendency to equate philosophy with the modern scholarly discipline by that name. But how shall we name the broader enterprise?

Here I think the poet Rainer Maria Rilke can help, offering in one of his famous letters to the young Franz Kappus an eloquent description of the philosophical attitude:

You are so young, so before all beginning, and I want to beg you, as much as I can, dear sir, to be patient towards all that is unsolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves like locked rooms and like books that are written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer. (Rilke, 1954/1901-8, pp. 34-35, emphasis in original)

One understandable reaction to this passage (indeed, it is the one I typically have) is to think that Rilke has gotten a bit carried away here. It is one thing to warn us against treating questions like problems to be solved. But to speak of loving ‘the questions themselves’ suggests a proscription against any sort of looking for, finding, or valuing of answers. And yet questions seem to ask for, point toward, and be fulfilled in answers.

There are two dangers to avoid in relation to questions. The first, emphasized by Rilke, is that we are typically all too impatient. Bothered by uncertainty, we have trouble letting a question breathe before smothering it with our initial response. The other danger, though, is that we might fall prey to an idolatrous love of questions. When we speak of the open question, we do not, as Gadamer (1960/2004) has shown, mean a question free of assumptions. This is what Gadamer calls a «floating question» (p. 357) noting that a true question is not open in this sense but opening. It is pointed, substantive questions that have the power to open up new worlds, new room to think, breathe, and move. If true questions are dynamic and then a true love of questions must involve following the action, not parking in front of a shrine to pure question-hood. With that caveat, though, we can appreciate Rilke’s challenge to master our impatience and learn to live with our questions. In this way, Rilke offers us a fresh translation of philosophia: philosophy involves trying to become a friend to the open question; it is a love for the openness a true question provides.

However, even if we agree to view philosophy in this more expansive light, we may wonder how this conception could possible apply to educational philosophy. After all, we typically think of education in terms problems and solutions, and we think of educational research simply as the cluster of applied social sciences that have sprung up around a particular instrumental institution (i.e., schools). It is one thing to talk about open-ended questioning in the liberal arts or even in the basic sciences, but isn’t such talk out of place here? To see education as a space of questions will require a significant act of reframing. Indeed, it will require me to do what the wise have always known to avoid: to advance and defend a definition of education.

3. The educational-philosophical triangle: the shape of humanistic conversation

Attempting to define education is notoriously difficult. Given the sheer diversity of educational aims and institutions (not to mention the fact that formal education probably constitutes only a small part of education as a whole), one faces a dilemma. If the definition is at all precise, it risks being wildly controversial, excluding by fiat many things that others consider to be prime candidates of ‘educationalness’. However, in attempting to be inclusive, we risk a definition so general that it is completely vague and uninstructive. For reasons that will become clear in a moment, I will choose to impale myself on the second horn of the dilemma. Indeed, in order to be sure that my definition is as broad as possible, I will build it not around the noun ‘education’—which may have a built-in bias toward formal processes and institutional structures—but will opt instead for the more open-ended adjective ‘educative’. And here is the definition I propose: Something is educative if it facilitates human flourishing.

As you can see, this definition is intentionally formalistic. The most determinate part of it, human flourishing recalls one of the famously begged questions in history. On Jonathan Lear’s (2000, lect. 1, esp. pp. 7-25) reading, the vagueness of Aristotle’s term eudaimonia is a kind of intentional enticement, as if to say: here is the central term around which your life is built, and yet you don’t really even know what it means. To know that I must pursue my eudaimonia is to know that I must seek to understand my eudaimonia: it is to confront Socrates’ famous question, how should one live? (Plato, 2004/c. 380 B.C.E., 352d). My definition is not meant to answer Socrates’ question, but simply to show that it arises whenever someone sets out to get or give an education. This definition merely foregrounds what we are doing when we claim that something is educative; we are describing a relationship between four terms: something, facilitates, human, and flourishing.

To venture an actual educational claim, one must fill in each of these terms with something more determinate. Each of the placeholders I have chosen is provocatively ambiguous, starting with ‘something’ which is the definition of indefinite. This term reminds us to ask: what (or who) educates? There are many possible claimants to educative power: solitude or relation (parenting, teaching, friendship or therapy?); work, play, study or travel; nature or culture (canonical works or everyday culture? creation or reception? same- or cross-cultural engagement?); language, discourse, or medium; institutions or practices (games, arts, sciences, humanities, or trades?); texts, experiences, environments or exemplars; novelty or repetition, success or frustration; exploration, instruction, observation, creation, conversation or meditation; the logical or the beautiful, the rule or the exception, the mundane or the transcendent. The term ‘facilitate’ is also meant to be generic, leading us to ask whether the educative usually comes in the form of freeing or shaping; shepherding or provoking; modeling, witnessing or dialoguing; enriching, preserving or winnowing; instructing, coaching, initiating or curing; or something else altogether?

A moment ago, I looked at ‘human flourishing’ as a phrase, but now I would like to consider these two words ‘human’ and ‘flourishing’ separately, each of which stands as another syntactical placeholder. The word ‘human’ in this definition explicitly begs the question of who is being educated. How do we understand the student of this proposed education? What are we assuming about what a human being is, can do, or needs? What parts of a human being do we deem educable and in need of education: body or soul; heart or mind; character, desires, emotions, self-understanding, imagination, or reason?

The word ‘flourishing’ stands to remind us that you cannot educate without some conception of what it means to be educated; you cannot say someone is growing up without some sense, however tacit, of what maturity looks like. Our educational aims are informed by ideals of the educated person which are themselves embedded in broader normative frameworks, in visions of human flourishing. I say visions, plural, because here again disagreements run deep. One person will say that flourishing means security and prosperity; another will counter that it means risk and adventure; a third will contend that it means reducing one’s carbon footprint. Do we best realize ourselves through inwardness and contemplation or through relation and practical engagement? Should a human life be measured by richness of experience, generosity to others, depth of insight, purity of motive, excellence of achievement? What is the most important thing to consider when trying to answer Socrates’ question: pleasure, virtue, joy, wisdom, freedom, fidelity, open-mindedness, transcendence, urbanity, authenticity?

Thus, far from trying to settle once and for all the question of what education is (as if the question is perpetually open), the point of defining the educative in this way is to remind us to pose the questions which usually get begged. It is a definition built to stage disagreements, a word which suggests neither settled answers nor radical incommensurability. The vagueness of the terms of my definition invites a diversity of replies, but at the same time collects those replies into one conversation. It is this conversation, I want to claim, that constitutes education itself. Education is the ongoing conversation taking place in the space opened by the question of what best facilitates human flourishing; it consists of the explicit and implicit answers, described and enacted, by those theorists, practitioners, and theorist/practitioners who feel called to join the conversation.

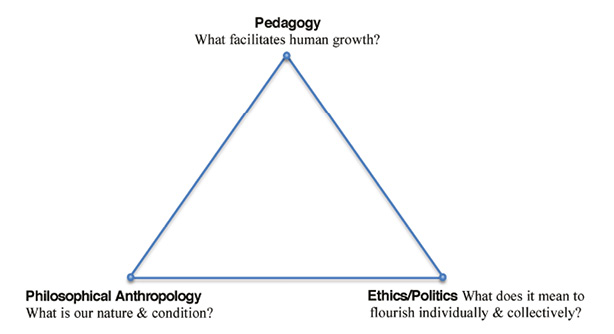

To claim that something is educative, then, is to encounter rival claims and to be propelled into a space of questions. I use the plural because clearly one need not explicitly or directly pose the question ‘What facilitates human flourishing?’ to participate. The point of listing the many alternative ways of taking each of basic terms of the definition was to show that there are an endless number of smaller questions that flow from and illuminate this central question. In order to have a dialogue across differences, though, the participants must share enough in common to constitute their differences as such; otherwise interlocutors merely talk past, and never quite to, one another. On the other hand, if one circumscribes too closely at the outset what there is to disagree about, one risks excluding from the conversation precisely those voices which promise to expand a debate narrowed by its unexamined assumptions. Each word of my definition suggests a question, or cluster of questions, implied in all theory and practice: in institutional arrangements, curricular designs, pedagogical strategies, educational policies. To be involved in education means taking a stand on some form of all three of these interconnected questions. It is to ask, ‘what is our nature, what constitutes individual and collective human flourishing, and what moves us toward this good given our condition? This compound question helps us to articulate the broad contours of educational inquiry, as illustrated in a figure I call the educational-philosophical triangle (see fig. 1).

Figure 1

The Educational-Philosophical Triangle

Source: Prepared by the author

According to the model I have proposed, three types of questions often thought to be distinct—the philosophical anthropological, the ethico-political, and the pedagogical—are in fact intimately related, all aspects of the basic educational question. To this the skeptical may reply that while it is all well and good to say that educators may want to consider the humanistic questions I’ve placed on the bottom of the triangle, to call all three categories educational does not seem accurate. My response is that in linking one obviously educational question with two traditionally humanistic ones, I am simultaneously reminding the humanities of their educational roots and reminding education of its humanistic dimensions. To bear this out, let us consider further the nature of each question, why each is inescapable for educators, and how all three are interconnected.

First, let us consider the ethical vertex of the triangle. Without a vision of the good life for human beings, one would not be able to make the countless qualitative educational decisions all educators must make. When teachers decide to adopt this tone rather than that, or to include one activity rather than another, they do so because they think that it will be better for their students. But ‘better’ is just a way of saying ‘closer to good’, and about matters of good there are no easy answers. Thus, underneath even seemingly superficial educational choices lie profound normative questions. Without some idea of what one ought to be developing into, how could we say whether a given change is for the better? When we strive to help someone mature, we rely on a vision of maturity. When we instruct, we rely on a vision of what it is important to learn, and therefore on what constitutes a truly educated person. Such issues open out in turn onto the fundamental questions of ethics: What makes life meaningful or rich? What are the most important human virtues and what does excellence in these areas look like? What is the collective good? How ought we best to live together? Whether or not educators pose these questions for themselves, they must at the very least have disposed of them with some received answer, for no one can attempt to foster human growth without the guidance of a vision of human flourishing, individually or collectively.

One cannot truly understand human flourishing in advance of, or abstraction from, our desire to become something good or our efforts to foster human development. Just as our visions of human flourishing inform our pedagogies, so our knowledge of what brings us closer to the good stands to teach us something about the good itself.

It is for this reason that I have I labeled the top vertex of the triangle ‘pedagogy’ rather than ‘education’: questions about what facilitates growth are just one aspect of the broader educational conversation. As I noted above, there are two closely related types of questions here: questions about what might constitute the prime catalyst of development (relationships, environments, texts, etc.) and questions about what metaphor best captures this catalysis (nurturing, instructing, challenging, etc.).

Here we must add a third coordinate to this map of educational questions. I used the word ‘human’ to refer to, without settling, debates about who or what is being educated, about the nature, needs, and capacities of our intended students. Underneath the differences lies the fact that every educational action and document is laden with assumptions about who we are and why we need education, about which parts of human beings are capable of education and which are recalcitrant. To theorize or practice education is to join the long the conversation I am calling philosophical-anthropology, wrestling with such questions as: What makes us tick? What are our fundamental capacities, needs, and frailities? What is the human condition? What is human nature? Are we essentially rational, appetitive, or imaginative beings, or are we so essentially cultural or historical in nature that no such generalizations across time and place are justified? This is not to suggest, of course, that educators do or should think about these questions in such abstract and grand terms. Educators are doing philosophical anthropology when they talk about ‘children’, ‘character’, or ‘emotional needs’, or when they justify their actions with reference to what a first-grader can handle, how to teach students with learning disabilities, how boys and girls learn differently, what reaches an angry student, and so on.

In a moment, we will look closely at the relationship between the bottom two vertices of the triangle, but I would like to make one observation straight away. Though all educational theories have both an anthropology and a vision of flourishing, one or the other may be left implicit. For example, developmental psychology is often introduced into educational debates as if data about how we develop could alone settle the question of how we should educate. What we should develop into is left more or less implicit. At other times, it is the ethical or political ideal that is foregrounded with key assumptions about our nature and condition operating in the background. Behind the calls to educate citizens, virtuosos, or critical thinkers lie assumptions about ‘savages’, ‘raw talent’, or ‘false consciousness’. We could say of the educator what we would say of the sculptor, that the tools chosen and the shapes attempted are different if one works in marble or clay. Or we could reject this pedagogical metaphor of molding and shaping as inherently miseducative. But notice that our critique will rely on some other vision of the human condition, holding that human beings are essentially free, dignified, guided by an inner daimon, or subject to some natural logic of development. One cannot educate without taking some stand in the sub-conversation I have been calling philosophical anthropology.

4. Taylor and the argument for strong interdependence

We have just seen some examples of how conceptions of human nature and human flourishing become intertwined in our educational thinking but let us consider the matter more closely. After all, contemporary philosophy is divided into sub-fields with some philosophers doing political theory, others working in philosophy of mind, and others specializing in ethics. In Part I of Sources of the Self, Charles Taylor challenges the tenability of this division of philosophical labor, developing compelling arguments for the interdependence of ethical and philosophical-anthropological views. Taylor’s first argument begins with the observation that the ‘most urgent and powerful cluster of demands we recognize as moral’ involves respect for the life and integrity of other people (Taylor, 1989, p. 4). These demands are often experienced on a purely ‘gut level’, but also always involve, according to Taylor, ‘acknowledgments of claims concerning their objects’ (Taylor, 1989, p. 7).

This means that in making moral judgments or in feeling moral emotions we are relying on a variety of rich and complex (though rarely articulated) notions about the way things are, and why and in which sense human beings are important; and these embedded views are ‘ontological’ in nature, concerning what exists and how it fits together in the largest sense. Taylor chooses the example of the sanctity of human life to highlight one constant component of these pocket ontologies we carry around, namely, a conception of human beings that helps us to recognize human beings as such and to understand why their lives are valuable. We might think that being human means having an immortal soul, being a locus of reason, or possessing a distinctive voice: the point is that some explicit or implicit assumptions about what makes us human are required to make moral judgments.

Taylor does not rest his case here, though, realizing that it begs an important question. If moral judgments involve substantive ideals, relying on thick background beliefs about the way things are, then part of this ontological background will concern philosophical anthropology. But Taylor recognizes that this is a big ‘if’ since many deny that moral judgments require this sort of philosophical heavy lifting. In one common conception—call it philosophical naturalism allied to moral subjectivism—morality is seen as a set of internalized taboos to help society run smoothly, or the projection of subjective preferences onto the world. To proponents of this view, ontological accounts of human nature and flourishing are worse than irrelevant to ethics, they are pre-modern, metaphysical fairy tales that rational people must learn to do without.

In light of this objection, Taylor launches a second argument, shifting from an external question about moral obligation (how ought one treat other human beings?) to an internal, ethical perspective. Like Williams, Taylor thinks that most of the strong evaluations we make in our lives extend beyond morality proper. When we wonder whether our lives are meaningful or rich, worry about our dignity or happiness or virtue, or otherwise wrestle what shape we should give our lives, we are engaged in ethical if not strictly moral reflection. Thus, Taylor is working against the modern ‘naturalist temper’ that would discount such prime ethical considerations as mere aesthetic preference or spiritual bunk (Taylor, 1989, p. 19). Taylor calls this second argument both phenomenological and transcendental: phenomenological because it proceeds from common elements of felt experience; transcendental because it then asks what must be the case in order for these to be elements of our experience (Taylor, 1989, p. 32).

The phenomenological observation is that people often ask themselves the puzzling question ‘who am I?’. It is puzzling because one would think that one wouldn’t have to ask or that one would need only recall one’s ‘name and genealogy’ (Taylor, 1989, p. 27). This leads Taylor to the following transcendental deduction: ‘the condition of there being an identity crisis is precisely that our identities define the space of qualitative distinctions in which we live and choose’ (p. 30). Identity would not be such a salient category for us were it not for the ethical distinctions the notion of identity embodies, if one’s identity was not something that one could be true to, betray, and so on. Knowing one’s name, rank, and serial number does not answer the question of identity which asks not only who one is but where one stands in relation to one what cares about and whether one has devoted oneself to the right things.

Thus, the process of understanding ourselves (philosophical anthropology) cannot be conducted without the use of strongly evaluative distinctions (ethics). As Taylor (1989) puts it:

What this brings is the essential link between identity and a kind of orientation. To know who you are is to be oriented in moral space, a space in which questions arise about what is good or bad, what is worth doing and what not, what has meaning and importance for you and what is trivial or secondary (p. 28).

The point of the transcendental argument is to show the unreality of the naturalist skepticism about whether such thick, background frameworks exist. Human life is already full of doubt, marked by sequences of orientation, disorientation, and reorientation. However, such self doubt only makes sense in the context of our background assumptions about what matters. Thus, to doubt the existence of the frameworks themselves makes little sense.

Taylor deepens this link between identity and strong evaluation through a second, related phenomenological observation: we make sense of ourselves through stories, we «grasp our lives as a narrative» (Taylor, 1989, p. 47). «What I am», Taylor writes, «has to be understood as what I have become» and in relation to «what I project to become» (Taylor, 1989, p. 47). Consider an analogy involving three characters, whom we will call A, B, and C. On a GPS device, we can confirm that all three are currently at a gas station in Toledo. But we don’t really know where they are until we learn more about their stories. It turns out that A lives in Toledo and works at this gas station every day. B is heading from New York to Wisconsin and just happens to have pulled over for gas. C grew up in Toledo, left after high school and has come back for the first time in twenty years because her dad is dying. My sense of who I am is dependent on my sense of where I am and this in turn requires that I tell myself a coherent narrative about where I have been and where I am going. Or as Taylor puts it, «our condition can never be exhausted for us by what we are, because we are always changing and becoming» (Taylor, 1989, p. 47). The question emerges always for humans, ‘Becoming what?’ When we ask ourselves, ‘What have I become?’ we do not do so with the cold neutrality of the laboratory scientist. We mean, ‘Where do I stand in relation to the good?’ Such stories are always ethical stories, even if not always explicitly so. The normative dimension may appear in the guise of humble adverb or vague adjective. However, when we report that we are ‘doing well’ or ‘feeling stuck’, ethical ideals are lurking in the background.

Here we need to recall Taylor’s distinction between weak and strong notions of evaluation. On the weak theory, we deem things good because we prefer them; on the strong theory, we prefer things because we deem them good. Taylor describes a ladder of strong evaluation from qualitative distinctions of better and worse, to the goods which help one explain why something is better or worse, to the hypergoods which organize a person’s goods (see, for example, Taylor, 1989, p. 63). ‘Orientation to the good’, Taylor writes, is ‘not an optional extra’ for making sense of our lives and there is no such thing as a human life that ‘makes absolutely no sense to the person who lives it’. ‘What is basic, then, to every human life as it is lived’, Taylor concludes, ‘is the operation of, more or less explicit, substantive ethical categories’. For Taylor, then, there are two closely related questions that necessarily arise for all persons: ‘Who am I?’ and ‘Where do I stand in relation to what I understand to be good?’ We are all ‘moral ontologists’ in our everyday lives.

With the help of Taylor, we can now see the inseparability of two of three questions which define the educational philosophical triangle. But as I have already indicated, the pedagogical serves as an obvious hinge between these other two basic questions. Given our nature and that which is good for us, the pedagogical question is: what best facilitates our development? In Taylor’s account, this pedagogical hinge between anthropological and ethical questions is left largely implicit, but it is not hard to locate in each of his case studies. Taylor begins with Plato, stressing the interconnection between Plato’s ethics of rational self-mastery and his conception of the soul as divided into higher and lower parts, and capable of becoming attuned to the order of the cosmos. Though Taylor does not highlight it as much as he might, he does note how Plato’s moral ontology relies on a crucial pedagogical insight, the distinction between instruction and conversion. Central to the famous ‘Allegory of the Cave’ and to the Republic as a whole is the idea that the highest form of education is not that of imparting skills or knowledge but of ‘turning the soul’ towards objects worthy of our attention (Plato, 2004/c. 380 B.C.E., p. 210 [Bk. 217, 516b-d]). And this does not even take into account the dialogical pedagogy enacted in Plato’s dialogues. If one reads Plato for what he shows as much as for what he says, then a dialogue like the Meno is primarily about pedagogy and only secondarily about the psyche (specifically, its capacity to recollect) and the good (specifically, excellence of character) (Plato, 1961/c. 380 B.C.E.).

Or consider Taylor’s discussions of Descartes and Montaigne. What Taylor wants us to see about Descartes is the way he heralds the move from rationality as a quality of the universe to which we align ourselves to an internal procedure that we utilize. But as it turns out, Descartes’ famous ‘method of rightly regulating reason’ turns out to be an autodidactive pedagogy, a skeptical, meditative process by which one expels faulty beliefs and builds a firmer foundation for true belief. Descartes explicitly introduces his famous thought experiments as the next step in his ongoing attempt to secure a sound education having tried both formal schooling and travel (Descartes, 1988/1637, Part 1). Central to Montaigne’s project is a different sort of self-educative process. As Taylor shows, understanding Montaigne’s ethic of self-awareness and self-acceptance and his vision of the self as inherently unstable goes hand in hand with understanding his novel project, his chronicling of personal impressions and assaying of self (Taylor, 1989, pp. 178-181).

5. Objections and implications

In this way Taylor helps us perceive the close connections between these three categories of questions and to deepen our sense both of the centrality of education to the history of ideas and of the importance of humanistic perspectives in education. These three questions—‘Who are we?’, ‘What ought we to become?’, ‘What improves us?’—are the quintessential humanistic questions. They are illuminated by all but the most sterile of humanistic works, including not only texts in a range of modern disciplines but also religious works, belles lettres, and the arts. The study of the good is not limited to philosophy, politics, and religion; nor do education departments have a monopoly on the question of human transformation. And of course, all of the humanities, as the name itself suggests, are attempts to illuminate what it means to be human by studying our inner lives and our artefacts (languages and laws, art works and buildings, theories and religions, treaties and sexual mores).

The implication of this, as I have suggested, is twofold: to be a reflective educator is to become a student of the humanities; but also, to be a true student of the humanities, to be a humane intellectual, is to be concerned with educational questions. What the triangle reveals is that far from being some recently invented, applied social science tagging along with the institution of schooling, education is the organizing principle of the humanities. Education is what brings the basic humanistic questions into relation and focus. The triangle equally pushes back against the aspects of the current self-image of the humanities. The conception of the humanities as separate disciplines tends to discourage the kind of synoptic thinking that brings the educational dimensions and interconnections among the humanities into focus; and the idea of humanistic work as research tends to discourage the recognition that humanities are not merely methods of knowing, but modes of self-knowledge which we pursue not disinterestedly but with an eye toward our own individual and collective self-cultivation.

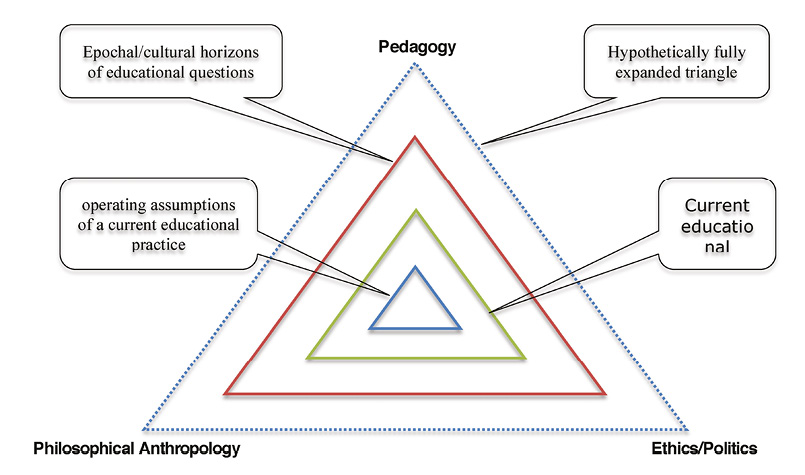

Here a problem for my account becomes clear. I have been arguing that education is an ongoing conversation about human becoming sparked by characteristic questions and sustained by the (philosophical) disposition to value these questions in their openness. The problem arises when we recall one of the conclusions of our discussion of Taylor, namely that the study of questions of human becoming is inevitably historical in nature. The thick, evaluative, arguable, more or less explicit beliefs about human nature and human flourishing he calls moral ontology find their place within languages of description which are situated in turn in traditions of thought and epochal horizons. The form of the questions available at any given time or within any particular traditions of thought always represents an interpretation of the questions, or a partial answer to them. A question mark does nothing to guarantee a true open question. One of the requirements of the true question we concluded was that a question needs a questioner; it needs to be posed by a flesh and blood person who feels a conflict on some issue of importance to him or her. Questions do not stand open because someone (like me) lists them on a diagram. The open question is the exception. Our everyday life, our habits and perceptions, is a fabric of answers, only to call them that suggests that we still can recall the questions which they have disposed. We are awash in truisms, beliefs so fundamental to our way of being in the world that they do not strike us as beliefs. When we find ourselves in the grips of a real question, we are foregrounding some aspects of the world, but by definition this means thrusting many others into the background. Being part of a way of speaking, a tradition of inquiry, bound to a time and place, means that certain questions captivate us more than others, and being open in one direction comes at the price of a radical blindness in another.

This raises two related difficulties for the triangle. First, how can I claim to be naming the questions themselves when they only show up in any particular time and place narrowed and foreclosed, and I myself am situated in such a contingent position? Second, by defining education around such vague questions as what is the human condition, am I not offering educators perfect examples of that species of pseudo-question which, we noted earlier, Gadamer calls the floating question?

Let me begin my response by acknowledging my situatedness. Like everyone’s, my approach to things is contingent on aspects of my background and surround, many of which operate utterly ‘behind my back’, as Gadamer would say (Gadamer, 1976/1967, p. 38). That there is no view from nowhere, however, does not mean that one can make no progress in widening one’s horizons. Devoting ourselves to unearthing hidden assumptions and seeing beyond false reductions of broad questions, we can make progress in eliminating some of the myopia entailed by our situatedness. In other words, while my account certainly does not presume omniscience, it does prescribe the project of attempting to free oneself from as much of one’s provincialism as one can.

Still, the question remains how I can claim to outline the three fundamental, open educational questions. Am I suggesting that everyone else is slowly struggling toward open-mindedness while I myself am already there, writing back to recommend the view? Clearly not: the triangle is intended as a heuristic device. And notice how, in introducing its three vertices, I found myself resorting to two strategies. On the one hand, I labeled each corner with exceedingly broad and vague placeholders (What facilitates growth? What is the human condition?). On the other hand, I drew up lists of rival questions characteristic of each vertex. On my definition, education is a space of disagreement, but of course disagreements are rarely just about answers. Most significant disagreements are disagreements about questions. The abortion debate would be a good deal less intractable if it were a debate between pro- and anti-life or one between pro- and anti-choice advocates.

Take the example of philosophical anthropology. No single question can be formulated that is broad enough to define this field of questioning for once and for all. Historically, the philosophical-anthropological question par excellence was ‘What is man?’, a question that now strikes most of us as dangerously parochial and universalizing at once. It was good for gathering together and putting into dialogue certain lines of questioning, but it did so at the price of submerging others. Now we are able to see how assuming that one could use the male pronoun as a gender-neutral universal made invisible entire areas of inquiry (concerning the role of gender in human experience), areas now central in our efforts to figure out what makes us tick. Meanwhile, the modern discipline of anthropology could be seen as an attempt to expand the pseudo-universal ‘man’, to learn from a variety of cultural groups what humanity means in its context so as to unlearn our tendency to see contingent features of European cultures as essential. That anthropology itself has had to be circumspect about its own tendency to ‘other’ (to superimpose the not-European on ways of life that are as different from what we are as what we are not) only further proves the point that broad phrases such as ‘human nature’ do not end but only exacerbate the controversy inherent in philosophical anthropology.

To pose the question in any particular manner is to show yourself already knee-deep in the controversy. When we ask ‘What makes humans tick?’, for example, we are already operating on the assumption that the most important thing to know about humans is what motivates them. Perhaps, too, the word ‘tick’ suggests further that this question of motivation is to be grasped as one of mechanical causes, that human beings are being tacitly understood as mechanisms. Compare ‘What makes humans tick?’ with another version of the anthropological question: ‘What is the place of the human being in nature?’. Each question will invite rival answers but there is an important tension in the questions themselves: one presuming that humans are best understood in isolation, the other that we must see ourselves in the context of our environment; one working from the inside out, one from the outside in. Now add a third question such as ‘What is the nature of human society?’, which assumes that we learn best about humans in their collective state, and suddenly assumptions common to the previous two questions come to light, namely that humanness is best understood individually rather than in relation, or in nature rather than in culture.

Therefore, no one single question can stand as the fundamental or general philosophical-anthropological question, for each question already presupposes a slew of philosophical-anthropological assumptions, bathing a portion of the field in light and the rest in darkness. We should not search for a single question neutral enough to open every possible question about human beings at once and for all time. This would truly amount to a floating question. A question this general would not open any doors; it would be empty, of little or no import. New vistas on the human are opened by grasping the limits of the older ones, by asking what a given view omits, obscures, distorts. The field as a whole, then, is best signified by a set of related questions that, in their proximity, highlight the truncations in each, all the while pointing to the common ground that must exist in order for these even to constitute rival assumptions. The common ground can be intuited but not, ultimately, named.

Nor could even a long list of questions, stated once and for all, collectively map the full boundaries of the conversation since a genuinely new question joins not as one more among the crowd, but shoves the whole lot to one side in a change of perspective. Learning to ask a new question requires more than putting a question mark on the end of some sentence which still remains intellectually declarative for us. One must be able to seriously entertain an alternative to put something in question. Another way to put this is that asking a new question involves a gestalt shift. It is as if one were surveying an elaborate highway system with a choice of many roads leading to a variety of places when suddenly one discovered a new means of transport which took one to places not even on the known map.

Thus the fully-open triangle is a fiction, and the questions I describe are only hypothetically open. I name them with banal, formalistic place-holders, to mark sites for potential expansions and revisions. I have chosen deliberately empty, even awkward, markers (e.g., ‘facilitates’, ‘flourishing’, and ‘ethico-political’) to point toward an openness we can only infer. But if it is a fiction, it is a useful one. Its formalistic openness invites us to put concrete, rival views from traditions at a critical remove from one another into a dialogue with each other so that a fusion of horizons occurs and we are able to glimpse a more open substantive question. In any one time and place, we will find ourselves bounded by the horizon of our assumptions. And of course we find still further reductions within our epochal horizons.

Consider, first, the common assumption that education means formal, intentional education, and the further equation of formal education with the contemporary «grammar» of contemporary, comprehensive public schools. Many avenues of educational inquiry are foreclosed as soon as we figure the learner as a student of compulsory, formal instruction and accept the whole architecture of classrooms, periods, subjects, credits, grades, and tests. And of course, in practice, the reductions go much further. Let us look briefly at each vertex of the triangle and its typical reductions.

The full conversation about individual and collective flourishing is almost always represented by the somewhat narrower consideration of our ideals of the educated person. But of course, it is rare to entertain even this broad a discussion of educational aims. Indeed, at one corner of the typical triangle are a handful of curricular objectives. That this represents a scandalously meager diet of the full regimen of ethical and political questions can be shown in two ways, one formal and one substantive. The formal complaint is that we substitute a nominalistic, bureaucratic ritual (every lesson must have a clear objective which must be briefly stated on the lesson plan and, depending on the school, on the board for students to see) for genuine, interesting, searching inquiry into what it means to be educated and to flourish individually and collectively. The substantive point is that not only are our educational aims reduced to labels and clichés, but modern, compulsory schooling is organized around a highly attenuated vision of the educated person. Character, emotion, and imagination have never been the strong point of schooling, in which the tendency has been to reduce learning to the memorization of information and the mastery of skills. In this new era of measurement mania, the reduction goes still further as more and more of the school’s energy gets taken up by helping students improve their scores on high-pressure math and reading tests.

Turning from ethics to philosophical-anthropology, we find a similar reduction as evidenced in the typical teacher-education curriculum. The vast and varied conversation about what it means to be human is reduced to a course in educational psychology, a unit on learning styles, and some readings on multiculturalism. Concepts like stages of development and personality types are always on the tip of our tongue, enabling us to make certain claims about what human beings are made of, while at the same time preventing us from enunciating many broader philosophical-anthropological questions.

Figure 2

Horizons of Educational Inquiry

Source: Prepared by the author

Even on the pedagogical corner of the triangle we find a significant narrowing of concern. Techniques of classroom management and other instructional methods tend to stand in for a more wide-ranging consideration of what facilitates human growth. In all of these areas, we see a tendency to get caught up in some specific debate whose back and forth conceals the exclusion of a whole range of key considerations. Thus, we become mesmerized by the see-saw between whole language versus direct instruction, or of one versus another developmental stage theory, and we fail to notice that the crucial, prior questions have begged (say, about the meaning of literacy and place of literacy in a good life, and of the place of modern developmental psychology in the broader philosophical-anthropological conversation). And of course, even a clichéd either-or represents too much indeterminacy when the class bell rings; in order to teach, the teacher needs workable answers to most educational questions. Figure 2 evokes the nested horizons of educational practice.

6. Conclusion

As schools of education are currently organized, philosophers of education lead a marginal and furtive existence. As education comes more and more to be understood as social scientific research into «what works» in the schools, philosophers seem like a poor lot indeed. We read slowly (we read!), we frequently commit the cardinal sin of citing works more than 10 years old, we have no data. Even our role in teacher education, once secured by the metaphor of foundations, is now questionable. Debates in teacher education are lively enough: Do teachers need more coursework or more clinical experience? And if they need more coursework, do they need more classes in curriculum and instruction or more background in their «content area»? Notice, though, that the kind of experience educational philosophers are best suited to provide for teachers is not even in the picture.

What is this experience? In a word, it is liberal learning about and for education. This is not the same as practical training in the craft of teaching or coursework in the learning sciences. Nor should it be confused with mastery of a liberal art as a content area (which in any case verges on a contradiction in terms). If education is a space of humanistic questions, philosophy a love of these questions in their openness, and educational philosophy the craft of keeping alive the texts and conversation that helps us re-open such questions, then philosophical teacher education is an invitation to teachers to be humane intellectuals of their field. It is an invitation to join a conversation of millennial interest.

Under the conception I have advanced, educational philosophy is far from marginal. It stands to remind how each positive program of research into what works begs key questions. And it stands to remind the university that, to paraphrase the famous essay by Sartre, education is a humanism. When education and the humanities are reconnected, as illustrated in the triangular rubric I have offered here, their place at the center of the university becomes clear.

References

Arrowsmith, W. (1966). The Shame of the Graduate Schools. Harper’s Magazine, 232(1390), 547-558.

Arrowsmith, W. (1967a). Graduate Study and Emulation. College English, 28(8), 547-558.

Arrowsmith, W. (1967b). The Future of Teaching: The Molding of Men. The Journal of Higher Education, 38(3), 131-143.

Arrowsmith, W. (1971). Teaching and the Liberal Arts: Notes Toward an Old Frontier. In D. Bigelow (Ed.), The Liberal Arts and Teacher Education: A Confrontation (pp. 5-15). University of Nebraska Press.

Barrow, R. (1983). Does the Question «What is Education?» Make Sense? Educational Theory, 33(3-4), 191-196.

Descartes, R. (1988). Discourse on the Method. Cambridge University Press.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. The Macmillan company.

Gadamer, H.-G. (1976/1967). On the Scope and Function of Hermeneutical Reflection In D. E. Linge (Ed.), Philosophical Hermeneutics (pp. 18-43). University of California Press.

Gadamer, H.-G. (2004). Truth and Method. Continuum. 2nd rev.

Higgins, C., Mackler, S., & Kramarsky, D. (2005). Philosophy of Education. In S. J. Farenga & D. Ness (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Education and Human Development (Vol. I, pp. 215-236). M.E. Sharpe.

Johnson, T. (1995). Discipleship or Pilgrimage? The Educator’s Quest for Philosophy. SUNY Press.

Langer, S. K. (1953). Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art, Developed from Philosophy in a New Key. Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Lear, J. (2000). Happiness, Death, and the Remainder of Life: The Tanner Lectures on Human Values. Harvard University Press.

Nietzsche, F. (1990/1874). Schopenhauer As Educator. In W. Arrowsmith (Ed.), Unmodern Observations: Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen (pp. 147-226). Yale University Press.

Nietzsche, F. (1990/1874-5). We Classicists. In W. Arrowsmith (Ed.), Unmodern Observations: Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen (pp. 305-388). Yale University Press.

Plato. (1961/c. 380 B.C.E.). Meno. In E. Hamilton, & H. Cairns (Eds.), The Collected Dialogues of Plato (pp. 353-384). Princeton University Press.

Plato. (2004). Republic. Hackett.

Rilke, R. M. (1954). Letters to a Young Poet (Rev.). W.W. Norton & Co.

Rorty, R. (1989). Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, C. (1989). The Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Harvard University Press.

Thoreau, H. D. (1986/1854). Walden. In Walden and Civil Disobedience (pp. 43-382). Penguin.

[1]. This is a revised and extended version of Chris Higgins, The Good Life of Teaching: An Ethics of Professional Practice (Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, pp. 254-73).