SITIO WEB: https://revistas.usal.es/index.php/1130-3743/index

ISSN: 1130-3743 - e-ISSN: 2386-5660

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.25394

Conceptual construction of global competence in education

Construcción conceptual de la competencia global

en educación

María SANZ LEAL, Martha Lucía OROZCO GÓMEZ & Radu Bogdan TOMA

University of Burgos. Spain.

msleal@ubu.es; mlorozco@ubu.es; rbtoma@ubu.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9845-0688;https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5547-8712; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4846-7323

Date of receipt: 04/01/2021

Date accepted: 03/04/2021

Date of online publication: 01/01/2022

How to cite this article: Sanz Leal, M.ª, Orozco Gómez, M. L., & Toma, R. B. (2022). Conceptual construction of global competence in education. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 34(1), 83-103. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.25394

ABSTRACT

Global competence as a learning objective has become relevant since its inclusion in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). Despite the growing interest in this competence, there are several issues requiring deep reflection, such as: What is global competence? How has it been constructed? From which approaches are the discursive processes for its construction based? And, what does intercultural education contribute to this construct? To answer these questions, this paper analyses the background, conceptualisations, approaches and theories on which the concept has been built, with special emphasis on interculturality as an educational approach and model that favours inclusion. The method used is a critical review and discursive analysis. It has been found that the instrumentalist approach to social efficiency has predominated in the conceptualisation, (at least as the underlying approach), as opposed to an approach of social re-constructionism that usually appears in the foreground. On many occasions the global competence and intercultural competence constructs are used interchangeably, although the former is more comprehensive in addressing the challenges of globalisation. Finally, it is highlighted that there are conceptual and measurement challenges and limitations that make it difficult to compare the acquisition of this competence at an international level and that therefore require more studies that systematically investigate the construction of the concept, its development and measurement.

Key words: educational theories; global competence; intercultural education; global citizenship education; competence-based education; transformative education.

RESUMEN

La competencia global como objetivo de aprendizaje ha tomado relevancia desde su inclusión en el Programa para la Evaluación Internacional de los Estudiantes (PISA). Pese al creciente interés por esta competencia, son numerosas las cuestiones que requieren de una reflexión profunda, tales como ¿Qué es la competencia global? ¿Cómo se ha construido? ¿Desde qué enfoques se parte en los procesos discursivos para su construcción? y ¿Qué aporta la educación intercultural a este constructo? Para dar respuesta a estas preguntas, este artículo analiza los antecedentes, las conceptualizaciones, enfoques y teorías en base a las cuales se ha construido este concepto, haciendo especial énfasis en la interculturalidad como enfoque y modelo educativo que favorece la inclusión. El método utilizado es una revisión crítica y un análisis discursivo. Se ha encontrado que en la conceptualización ha predominado el enfoque instrumentalista de eficiencia social, aunque sea de manera subyacente, frente a un enfoque de re-construccionismo social que suele aparecer en primer plano. En muchas ocasiones los constructos competencia global y competencia intercultural se utilizan indistintamente, si bien la primera resulta más integral para afrontar los desafíos de la globalización. Por último, se señalan desafíos y limitaciones conceptuales y de medición que dificultan la generalización y comparación entre estudios a nivel internacional de la adquisición de esta competencia y que requieren por tanto de más estudios que investiguen sistemáticamente la construcción del concepto, su desarrollo y medición.

Palabras clave: teoría de la educación; competencia global; educación intercultural; educación para la ciudadanía global; educación basada en competencias; educación transformadora.

1. Introduction

The current global context demonstrates the degree of interconnection and interdependence that exists between countries, cultures and societies around the world. Perhaps the pandemic caused by the Coronavirus illness allows such global interdependence and the vulnerability of states to be revealed. Furthermore, the migrant and refugee crises, global warming and the consequent climate change, and the healthcare and financial crises reflect the phenomena related to the effects of globalisation that we face in the 21st century. Environmental sustainability, cultural diversity, and the reduction in inequity and poverty are ongoing challenges on the current agenda and issues to which education must respond. The 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda indicates that all educational actions should be connected to Target 4.7 of the Sustainable Development Goals:

Ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development (UNESCO, 2015, p. 22).

To respond to the challenges caused by globalisation, different education models have emerged, [1] such as Global Citizenship Education (GCED), democratic education, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and intercultural education. Although the models differ in terms of focus and scope (cosmopolitanism, promotion of human rights and active participation, environmental sustainability and cultural diversity), they do share a common goal in fostering global understanding, positive relationships, and active and transformative participation in and for society.

GCED and ESD facilitate the understanding of the economic, social, cultural and political interrelations between the Global North and the Global South, fostering values and attitudes related to solidarity and social justice. The first focuses more on achieving human and sustainable development, while the second on fostering responsible and active people. Intercultural education focuses on favouring positive and enriching interactions between individuals from diverse cultures and democratic education is based on the Declaration of Human Rights, active participation and on individual equality in decision-making. In this paper, we focus on the contribution of intercultural education as we believe that where the effects of globalisation most materialise and are observed in schools is in the cultural diversity of each classroom, which serves as an opportunity to establish links with all the dimensions of global competence that will subsequently be seen.

In turn, the rise of a focus on competence-based education (CBE) driven, among others, by the need to develop extensive capacities in people that allow them to adjust to changing situations, has led to the emergence of conceptualisations such as intercultural competence, democratic competence and global competence, linked to those global education models.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) through PISA evaluates the level of students at the end of compulsory education and an innovate area is included each year. In 2018, it was global competence. The organisation defines global competence as: «the capacity to examine global and intercultural issues, to understand and appreciate different perspectives based on respect for human rights, to engage with people from different cultures, and to act for collective well-being and sustainable development.» (OECD, 2018, p. 5).

Recent theories of the «new sociological institutionalism» suggest that there are global mechanisms that influence local educational policies (imposition, harmonisation, dissemination, standardisation and installation of interdependency) in which the international organisations are transmitters of ideas of global education, which are usually of an instrumental nature and geared towards the market (Hajisoteriou & Angelides, 2016, cited in Hajisoteriou & Angelides 2020, p. 150). Standardisation is carried out through globalised assessment processes, like international performance tests, such as PISA.

In the Spanish context in which the study is based, the global competence concept has hardly been theorised, with intercultural education and education for development and global citizenship[2] being those most developed, similarly to what occurs in Germany, where global competence is debated, especially with regard to education for global and sustainable development (Sälzer & Roczen, 2018). The report of the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training (MEFP, 2020) sets out the results of the 2018 assessment on global competence so that, in general terms in Spain, 68% of students achieve or pass the basic level of performance in global competency.

In this context, several research questions arise, such as what is global competence? How has it been constructed? From which approaches are the discursive processes for its construction based?

And, what does intercultural education contribute to this construct?

This paper seeks to provide answers to these questions, proposing a conceptual framework that allows research to continue on global competence, its development and evaluation. To do that, backgrounds, conceptualisations and theories have been taken into account that are considered valid for the correct positioning of the study, as recommended by Hernández et al. (2010), helping to conceptualise what is understood by global competence and what aspects are related to inclusive education from an intercultural approach.

Ultimately, how global competence has been constructed, the approaches used and purposes sought, the challenges and limitations entailed and the future lines of research considered necessary are explained.

2. Theoretical background

Competence-based education has entailed a profound change in the way education is understood. In recent reviews, its emergence was placed at between the end of the 1980s and the mid-1990s, when it was truly propelled with the report led by Delors et al. (1996) for UNESCO, following the project, Definition and Selection of Competencies (DeSeCo) of the OECD (2005), identifying and defining the key competencies required for future generations and their capacity to manage in a rapidly changing world.

Few studies provide their own definitions of the term ‘competence’ and the majority adopt already consolidated theoretical frameworks, most adhering to the theoretic framework proposed by the OECD that is used as an authoritative source that is not questioned, analysed or extended (García, 2008; Ortiz-Revilla et al., 2020; Tahirsylaj & Sundberg, 2020).

The DeSeCo framework sets out three broad categories of key competencies: acting autonomously, using tools interactively and interacting in heterogeneous groups; the last category has a lot of influence on global competence, as will be seen later on. The European Commission used the DeSeCo project and the proposal by UNESCO in its joint recommendation with the European Parliament and the Council (2006) on the key competencies for lifelong learning (2006/962/EC), contributing, in turn, to the establishment of eight key competencies recommended for adoption within the European Union, some of which include communicating in foreign languages, social and civic competencies, and cultural awareness and expression closely related to global competence.

In educational research, the generic definition of competence includes knowledge, skills and attitudes (and, sometimes, values) geared towards action, which is how global competence is defined. It also indicates that research on the competencies in education is largely aimed at general competence and when it is specified on a subject-area, science, maths and technology are shown to be over-represented (García, 2008; Ortiz-Revilla et al. 2020; Tahirsylaj & Sundberg, 2020).

3. Methodology

In accordance with the types of literature reviews proposed by Grant and Booth (2009), this study is based on critical reviews insofar as: (i) the search is not exhaustive, (ii) it presents the results in a narrative and chronological manner, and (iii), from the analysis of the studies, a conceptual contribution is made to the current theory. This type of review seeks to identify what has previously been achieved and it is usually used for general debates and to make up for a lack of knowledge on a subject-matter. In this case, it regards the absence of reflection and debate on global competence in the Spanish context, allowing for consolidation and providing future researchers with a prior study.

To avoid the possibility of bias that this type of review may entail, some authors suggest the need to set out the search process (Guirao Goris, 2015). In this regard, this critical literature review encompasses the origin of the concept and the most recent frameworks that, in some cases, are found in institutional documents that don’t appear in databases, motivating the selection of this method. The search was conducted over the months of May and June 2020, and the databases of SCOPUS, Web of Science and Dialnet were consulted, using the descriptor «global* competen*» and the corresponding words in Castilian Spanish. The asterisk (*) symbol was used as a truncation to search for different variants of the term ‘globally/global’ and ‘competencies/competence’. Documents published in English and Spanish from 2001-2020 were selected. The search finalised with the reading and tracking of bibliographies referenced in the documents, allowing for a chronological analysis, characteristic of this type of review (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 94).

3.1. Discourse analysis

Exploring and mapping the way in which global competence has been established and defined, requiring a theoretic framework that allows the distinct approaches in the discursive processes for its construction to be differentiated. Tahirsylaj & Sundberg (2020) suggest that, to differentiate between distinct aspects for the conceptualisation of the competencies, it is necessary to examine, in addition to the explicit definitions of competencies, the implicit assumptions that are taken for granted. The authors call those assumptions ‘background ideas’ and the explicit definitions ‘foreground ideas’.

The background ideas are core principles that are taken for granted and institutionalised, and rarely contested except in times of crises. The foreground ideas, on the other hand, are the ideas and concepts structuring education programmes and reforms in policy-making. These ideas and definitions are used in discursive interactions to maintain and/or alter institutions and their patterns of action. (Schmidt, 2015, cited in Tahirsylaj & Sundberg, 2020, p. 133)

Tahirsylaj & Sundberg (2020) suggest that the background ideas that encompass the most commonly used definitions of CBE have a clear pattern where the dominant paradigms that influence the definitions are mainly related to social efficiency and theory of human capital (Deng & Luke, 2008).

The competencies are set out as the most important and fundamental resources for people to adapt to the knowledge economy. However, the dominant foreground ideas, that is, those that are explicit in defining CBE, do not originate from the theory of human capital, but rather the ideology of the learner-centred curriculum. In other words, there is a tendency to assume the competencies from a technical or professionalising perspective, despite being presented from references and theoretic arguments of a humanistic and formative viewpoint. (Ortiz-Revilla et al. 2020; Tahirsylaj & Sundberg, 2020).

These conclusions arise from contrasting the studies with the four main curricular paradigms with historical and current influence on the objectives of schooling considered by Deng & Luke (2008) and Schiro (2013): ‘academic rationalism’, which places importance on disciplinary knowledge; ‘social reconstructionism’, where the aim of education is to facilitate social justice to help end inequalities; ‘social efficiency’, for economic and social productivity that allows for the perpetuation of society; and, finally, the ‘learner-centred curriculum ideology’, the focus of which is not on academic disciplines or the needs of society, but rather on the needs and interests of individuals to foster their personal development and self-realisation (humanism).

In the following sections, the background ideas and the foreground ideas of documents that have provided consolidated definitions for global competence in light of the aforementioned four paradigms, such as the logic of research and prior categories in the discourse analysis established by Santander (2011, p. 214), are explored.

4. Building global competence

The conceptualisation of global competence has largely been developed in the United States and by supranational institutions, such as the OECD and UNESCO. In the case of Spain, the references found to this concept related to education in general are very recent and use the definitions proposed by the PISA 2018 framework, like Cornejo & Gómez-Jarabo (2018) and Heras et al. (2019) or the proposal of Boix-Mansilla & Jackson (2013) in the work of García-Beltrán et al. (2019).

The challenge of defining global competence has gone hand in hand with the quick, growing and critical need of international schools and universities (Auld & Morris, 2019; Hunter et al., 2006; Kim, 2019). International education[3] is seen as a precursor of the creation and fostering of global competence through international mobility, exchange programmes, the learning of languages and promotion of bilingualism (Lambert, 1993).

Reimers (2010) believes that global competence has been developed to date in families, schools and universities of the elite through the command of foreign languages and global subjects for specialists in certain study fields, and that these competencies are needed for most of the world’s population, not just for a few: «global competence should now be a purpose of mass education, instead of just elite education»(Reimers, 2010, p. 186).

4.1. Origins of the concept

According to Hunter (2004) global competence was mentioned for the first time in 1988 in an international education initiative published in a report by the Council on International Education Exchange of the United States of America. In the 1990s, several international conferences took place dedicated to defining global competence from the area of education policies and through their reports we can extract how this concept was created. In a 1993 report, some of the focuses of global competence, its dimensions and a number of proposals for its definition started to emerge. Said report states that addressing global competence can be done from the perspective of international exchanges, citizenship education, diversity and multi-culturalism or the training of language-study specialists and teachers (Lambert, 1993).

Richard D. Lambert, considered to be the father of global competency, refers to a special personal quality that has also been called ‘awareness’ or a ‘global or cosmopolitan perspective’, and establishes five components: knowledge (of current events), empathy, approval (positive attitude), foreign language competence and task performance

(ability to understand the value in something foreign).

The relation between global competence and business and working life is continuous. The 1998 report, Educating for Global Competence: America’s Passport to the Future», is more explicit, explaining global competence as higher education for the development of human resources for a world economy and US leadership. Its aim is to demonstrate the importance of international cooperation in the area of education and development for the economic and political future of the nation and to incentivise the association among governments, companies and universities to include in curriculums an international dimension that prepares teachers and a workforce capable of competing in global markets (American Council on Education, 1998). Although environmental sustainability, concern regarding refugees and the defence of human rights are also mentioned, it is done so from the perspective of being a threat to the prosperity and security of the United States.

4.2. Definitions, conceptual framework and evaluation proposals

The definitions most used, together with their authors and the approach considered by each source to be most significant, based on the four paradigms with historical and current influence on the aims of schooling, explained in the methodology section, are set out in Table 1. The categorisation of said approaches and from which the foreground ideas and background ideas have been considered, has been undertaken through a critical analysis of the discourse of the documents referred to, following the indications of Santander (2011, p. 216) in which the unit of analysis is sentence-based. As such, in some cases in the subsequent analysis, literal expressions from the documents are used in order to illustrate the corresponding approach.

Table 1

Foreground ideas vs background ideas in global competence

|

SOURCE |

DEFINITION |

Background Ideas |

Foreground ideas |

|

(American Council on International Intercultural Education, 1996) |

Ability to understand the interconnectedness of peoples and systems, to have a general knowledge of history and world events, to accept and cope with the existence of different cultural values and attitudes and, indeed, to celebrate the richness and benefits of this diversity. (p. 2). |

Social efficiency |

Social reconstruction |

|

«Having enough substantive knowledge, perceptual understanding and intercultural communication skills to interact effectively in our globally interdependent world» (p.117). |

Social reconstruction |

Social reconstruction |

|

|

(Hunter, 2004) |

«Having an open mind while actively seeking to understand cultural norms and expectations of others, leveraging this gained knowledge to interact, communicate and work effectively outside one’s environment» (p. 101). |

Social efficiency |

Social reconstruction |

|

«The knowledge and skills that help people understand the flat world in which they live and the skills to integrate across disciplinary domains to comprehend global affairs and events and to create possibilities to address them. Global competencies are also the attitudinal and ethical dispositions that make it possible to interact peacefully, respectfully and productively with fellow human beings from diverse geographies» (p. 184). |

- |

Social reconstruction |

|

|

(Boix-Mansilla & Jackson, 2011) |

«Global competence is the capacity and disposition to understand and act on issues of global significance» (p. 13). |

Social efficiency |

Social reconstruction |

|

«The capacity of an individual to understand that we learn, work and live in an international, interconnected and interdependent society and the capability to use that knowledge to inform one’s dispositions, behaviours and actions when navigating, interacting, communicating and participating in a variety of roles and international contexts as a reflective individual» (p. 9). |

Social efficiency |

Social reconstruction |

|

|

«It is a goal of multidimensional and lifelong learning. Competent individuals on a global scale can analyse issues of local, global and cultural relevance, understand and appreciate different perspectives and views of the world, successfully and positively interact with different people, and responsibly act towards sustainable development and collective well-being» (p. 5). |

Social efficiency |

Social reconstruction |

|

|

(Boix-Mansilla & Wilson, 2020) |

«The life-long process of cultivating oneself, one’s human capacity and disposition to understand issues of global and cultural significance and act towards collective wellbeing and sustainable development» (p. 11). |

- |

Learner-centred approach |

Source: Own elaboration

Olson & Kroeger (2001) relate the gaining of a second language, experience abroad and intercultural sensitivity in order to assess global competence. They understand that our employment and life decisions are of a global nature and practically all human interaction is an intercultural encounter. They provide a more centred approach on aspects of intercultural competence guided by Bennetts’ model of intercultural sensitivity, offering a definition proposal of global competence that starts to reveal how it is constructed by several dimensions, in which intercultural relations are also important. «… enough substantive knowledge, perceptual understanding and intercultural communication skills…» Olson & Kroeger, 2001, p. 117).

Hunter (2004) through a Delphi international panel offers a definition that also includes aspects related to intercultural competence. Hunter also cites authors such as Wilson & Dalton (1997) and Curran (s.f.), who bestow on global competence perceptual understanding, which refers to aspects related to an open mind that actively seeks to understand cultural norms and expectations of others, resisting stereotypes.

This author, in addition to providing a conceptualisation, also seeks to verify if the perspectives on global competence of the recruiters of multinational companies and university educators coincide, showing a clear social efficiency approach: «...which led me to seek to bring together educators and those who need their product (businesspersons)» (Hunter, 2004, p. 104).

Fernando Reimers, puts forward the first proposal that the OECD should evaluate global competencies (Auld & Morris, 2019). The author believes that the economic advantages that arise from world competition have received more attention than civic advantages, when global competence is not only useful from an economic perspective, but also as a cornerstone of democratic leadership and citizenship. He understands global competence as a set of knowledge and skills that allow people to understand the world and its challenges in such a way that they can create possibilities to address them, as well as an attitudinal and ethical willingness that allows for peaceful, respectful and productive interaction between people of diverse geographies. He combines three dimensions: affective, action, and academic, specifying in different aspects such as: character development, affection and values; skills and the development of motivation to act; and an aspect based on the development of cognition, knowledge and capacity to understand world problems (Reimers, 2010, p. 185).

Reimers places significant value on knowledge and appreciation for human rights as a common basis for the first dimension of global competence, the ethical dimension. He also insists on the opportunities that students have in school for meeting and collaborating with other persons from diverse cultural, racial and socio-economic origins through relations with school personnel, students, parents and other members of the community.

Boix-Mansilla & Jackson (2011) provide the framework «Educating for Global Competence: preparing our youth to engage the world». They justify the need for global competence in three aspects: The global economy and changing demands of work, global migration with the resulting diversity as a norm, and climate instability and environmental management. They state that preparing the youth for the future goes beyond preparing them for university and work life. They understand that globally competent people are aware, curious and interested in learning about the world and how it works. The authors establish four basic capacities associated with global competence: investigating the world, recognising perspectives, communicating ideas and taking action. In addition to a justification for global education and a conceptual framework for global competence, they develop four associated basic capacities and their relations, basic principles for teaching competence and recommendations so that schools and institutions foster a culture of global competence.

Furthermore, the OECD in its first key document (OECD, 2014) related to global competence, commissions the definition of a framework for PISA 2018 that covers the attitudes, behaviour, knowledge and skills that students should have on finalising education in order to have success in their future studies and career. In this report, a definition is provided that will continue to evolve until the final definition of the OECD (2018) framework is obtained. According to Sälzer & Roczen (2018) the OECD in 2015 sought to bring together the concepts of global citizenship, intercultural competence and knowledge on globalisation in the idea of global competence.

Lastly, a recent study conducted in Chinese schools provides a culturally informed reinterpretation of global competence using on the model of Boix-Mansilla & Jackson (2011), which commences with a type of learning based on the capacity to understand, delving deeper into the subject matter and into the disposition of students relating to globally competent thinking and behaviour, allowing for long-lasting learning (Boix-Mansilla & Wilson, 2020). The re-conceptualisation they propose is based on research on Chinese traditions and practices in education and on the ideas provided by teachers, which entails including the oriental approach that links education to the objective of achieving «self-perfection», dedicated to learning and cultivating values, where learning and knowledge are not geared towards the outside world, but rather towards oneself. They see global competence as the life-long process of the making of a moral person ‘zuo ren’, a moral compass rooted in human dignity and social harmony that informs individual and collective action in the world. As such, they include in the framework a natural element that symbolises the long-term development of capacities and the cultivation of oneself at the centre.

The foreground ideas largely fit into a social reconstruction approach and the background ideas into a social efficiency approach, for economic and social productivity (American Council on Education, 1996, 1998; Boix-Mansilla & Jackson, 2011; Hunter, 2006; OECD 2018). Olson & Kroeger (2001) adopt a background approach of social reconstructionism centred on aspects that influence relationships between people, while Boix-Mansilla & Wilson (2020) consider a contribution aligned with a foreground idea relating to the ideology of the learner-centred curriculum, with a clearly humanistic approach.

The background aspects that influence most of the conceptualisations reviewed include global understanding, evaluated by Barrows et al. (1981), the concept on global perspective (perspective consciousness, state of the planet awareness, cross cultural awareness, knowledge of global dynamics and awareness of human choices) of Hanvey (1975) and the intercultural sensitivity model of Bennet (1986).

5. Contribution of intercultural education to global competence

Education is an intrinsically political matter. The way citizens are educated is related to the kind of society we want to achieve. In the educational field in general, global competence, in the case of Spain, is usually considered as an answer to changes in the national population due to immigration and as result of the need for a more inclusive model of citizenship (Auld & Morris, 2019; Cornejo & Gómez-Jarabo, 2018; Goren & Yemini, 2017).

As Abdallah-Pretceille (2001, p. 57) suggest, heterogeneity has been and is still considered a handicap, a source of problems and difficulties in education, that justifies compensatory and segregational measures, and expectations and beliefs of teachers regarding students of a migrant background, often entailing differentiated school groupings (Castejón & Pàmies, 2018). There is a strong tradition of education homogenising that has led to assimilationist conceptions based on ethnocentric ideas that prioritise some cultures over others and that also do so based on social categories (nationality, ethnicity, etc.) that prevent the individual and inherent characteristics of each person from been discovered. Therefore, in both Europe and the US or Latin America, misunderstood intercultural education is often identified as a means to integrate immigrants, indigenous people or people of other ethnicities into the culture of the reception country or the most prevalent culture. That perspective has led to practices related to compensatory education, unequal relations tinged with paternalism or making cultures into folklore (Aguado, 2003; Deardorff, 2009; Leal, 2016).

Being aware of this tradition of education homogenising, which has its roots in the Taylorist education model of the 19th century, connected to producing a workforce from a social efficiency approach that also predestines students based on their social conditions (origin, social class, sex, etc.), the possibility that global competence may influence said approach is considered. Therefore, the need to look at the global competence approaches that are closer aligned to social reconstructionism and humanism, which help to foster and increase the capacities and potential of each person to improve his or her life as active agents that transform society, contributing with it more inclusive education, is insisted on. The intercultural approach is proposed by authors such as Aguado & Mata (2017) as a glimpse that allows one to understand the complex interaction between cultural diversity and educational equality. Cultural differences are always present in all groups educated, human diversity is recognised as being normal, heterogeneity as richness and homogeneity as a coercive manner and, therefore, contrary to the democratic principles of equality.

The ‘inter’ prefix of the word intercultural, is key in this research and action paradigm on education, where a relationship is established between the ‘I’ and the ‘You’, recognising each other. According to Abdallah-Pretceille (2001, p. 39): «individuals are increasingly less determined by the culture they belong to; they are not a product of their culture, but rather, conversely, the actor or agent of it through interaction.» The intercultural approach places emphasis on relations more than on cultures or individuals and, from that perspective, different cultures are defined as dynamic relationships between two entities that give each other meaning. One of the dimensions of global competence refers to perceptual understanding, a necessary ability in people to favour such relations in a positive way.

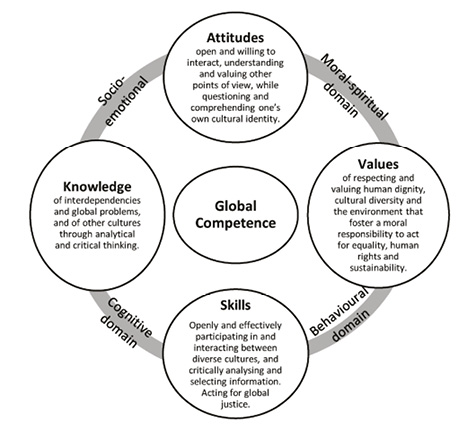

Perceptual understanding is not the only ability required for such relations to be as equal and enriching as possible. Despite differences in the wording, there is a consensus on the dimensions set out in figure 1, which contemplates global competence, knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that relate to cognitive, socio-emotional, attitudinal or behavioural and moral-spiritual development. All the dimensions are inter-related and have a direct connection with intercultural education. From our standpoint on social reconstructionism and learner-centred approaches, we understand that they favour educational inclusion.

Figure 1

Dimensions of global competence

Source: Adapted from Boix-Mansilla & Jackson, 2011; OCDE, 2018; Reimers, 2010

These dimensions require initial self-knowledge. Inside-to-outside work is required that is conditioned to a necessary understanding of ourselves, of the environment that influences us, and of our place in the world as an essential basis for understanding those around us. Aguado (2003), in the description of intercultural competence, says that intercultural attitudes «imply disposition or willingness to question our own values, beliefs and behaviour, and not assuming that they are the only ones that are possible or correct...» (p. 141)

In addition to that already set out, it is highlighted that intercultural education contributes to global competence:

– Attitudes as a necessary basis on which to develop the rest of the skills connected to intercultural competence and that translates into the development of global competence, according to Deardorff (2009) and Cushner (2011).

– The necessary transformative approach of global citizenship that improves democracy, fostering equality and social justice through participation in conditions of equality of all actors in education (Banks, 2014).

– The contact hypothesis developed by Allport (1954), when designing programmes that foster the development of global competence and that considers the following principles: a) individuals having equal status; b) sharing common objectives; c) cooperation between groups, and d) authority-supervised contact, such as teachers.

6. Limitations and challenges in the conceptualisation of global competence

The aim of being a universal concept is a challenge that has always accompanied the construction and assessment of this competence. When the global awareness survey of Barrows (1981) was designed, it was questioned whether or not those surveyed should be members of a single country or of several in order to make it more international. It is considered whether that would be a solution or if it would be falling into the habitual categorisation of identifying diversity with nationality, (Aguado, 2009) when, in addition, the actors involved in constructing the frameworks of transnational institutions usually form part of discursive coalitions of actors that «speak the same language» (Nordin & Sundberg, 2016, p. 320).

As has been stated, there is extensive literature that affirms the existence of global mechanisms of influence in local educational policies. Hunter et al. (2006) relate global competence with the term ‘soft power’, coined by Joseph S. Nye, which is that that defends the world order of the US, which makes others like and voluntarily support the American system compared with ‘sharp power’, which entails the use of violence, in other words, one that could be seen as subtle imperialism. That may serve as an incentive to propose more culturally informed interpretations like that put forward by Boix-Mansilla & Wilson (2020).

The fact it is a relatively new concept requires caution when adopting a theoretical framework that provides a definition and a valid measurement instrument. However, the introduction of a global competence measure in PISA may lead to the definition and assessment put forward by that institution, which has worldwide recognition and a significant impact, being understood as definitive and exclusive, limiting the research on its conceptualisation. Several authors have criticised the framework for the global competence of PISA 2018 based on different arguments, among which, the inclusion of exclusively Western perspectives, «the South once again appears to be irrelevant for the discourse. The authors of the final OECD document eliminated the voices and scientific sources of the South between the first draft (2014) and the final document (2018)» (Grotlüschen, 2018, p. 199). Similarly, Engel et al. (2019) state that it is difficult to compare on an international and intercultural level the attainment of this competence due to the lack of consensus and transparency. They suggest that before administering the assessment, the OECD should have been more methodical and transparent in terms of the aspects of global competence considered universal and those that can be better defined and measured on a local level.

Several authors that participated in the development of the assessment for the global competence of PISA 2018 have set out the challenges found in producing an assessment that is internationally comparable and that can be standardised. To address the challenge of incorporating into one test the extensive range of cultural and geographical contexts represented in the participating countries, PISA developed two assessment instruments: a cognitive test and a context questionnaire. Sälzer & Roczen (2018) explain that in the cognitive assessment, it is difficult to establish grades in some subdimensions of correct or incorrect for a construct like global competence that is not applicable to purely science-based domains, and that the context questionnaires often include stereotypes and a bias for social desirability. Some of these observations may have been the reason why around 30 countries decided not to apply the assessment of this competency in 2018 (Sälzer & Roczen, 2018, p. 6) or why only 39 countries only applied the context questionnaire (MEFP, 2020).

Another criticism of the construction of the PISA framework is that it changes from an instrumental approach of workers with a «global mentality» to an approach on global issues and intercultural sensitivity, in addition to the ad-hoc alignment process with the SDGs, particularly in the final document. Another point mentioned regards an adaptation in order to be more easily measurable, which aligns global competence with the assessment, given that, for example, comprehension can be measured more easily than critical reflection (Auld & Morris, 2019; Sälzer & Roczen, 2018).

One aspect that the PISA framework does take into account with regard to measurement through the student self-assessment questionnaire is linguistic competence, which is closely linked to communication in multicultural contexts. The challenge that arises regarding it, according to PISA (2018), is the difficulty of protecting and reviving aboriginal languages.

As regards the ways in which to acquire global competence, an extensive debate is ongoing. As previously mentioned, studying abroad is one of the most encouraged measures, but, often, that is not an option for everyone, does not guarantee in itself the development of the competency and it doesn’t have to be the only way of developing it (Parkhouse et al., 2016). Authors, such as Doerr (2020) suggest valuing the potential of immigrant students as possessors of global competence that can contribute to its development if their participation is facilitated.

As such, limitations and challenges are found that, as Sälzer and Roczen (2018) suggest, can be overcome if time and effort are put into systematically examining the construction of the concept, its development and measurement.

7. Conclusions

The review has shown that in the conceptualisation of global competence the instrumentalist approach of social efficiency has been predominant, albeit in an underlying manner compared with the social reconstructionism approach that usually appears in the foreground. The approach centred on the development of people and their potential is in the minority. However, readers should take into consideration that these statements arise from a review that helps to go beyond the limited scope of systematic reviews, but that entails the possibility of bias as a flaw. As such, more specific and systematic studies are required.

This study highlights the inherent limitations to the conceptualisation of global competence, and encourages reflection on: what approach is established in the research for its development? How can it be assessed? And, how can it be developed in different target groups? In this regard, this paper provides four paradigms (academic rationalisation, social reconstructionism, social efficiency, and the learner-centred curriculum ideology) as a framework for identifying the approach in developing global competence. Furthermore, it is concluded that the importance of intercultural education in global competence is very significant, and it is one of the global education models most referenced and influential in the different subdimensions of this competency. This model allows the current challenges regarding assessment of global competence, as well as the programmes for its development, to be addressed. One of the key elements that this model provides is the importance of self-knowledge and personal attitudes as a fundamental basis for developing other dimensions. Teachers of education based on the principles of intercultural education must take advantage of the cultural diversity present as a means by which to develop global competence.

Researching, both on a theoretical and empirical level, the definition, measurement and development of global competence is an aspect of educational relevance, due to the fact that its attainment favours a society that can overcome the challenges of globalisation. In light of the foregoing and looking at global competence from the social reconstructionism and learner-centred approaches, to continue researching and delving deeper into the development and assessment of this competence, we propose the following: understanding global competence as a goal of lifelong learning based on self-reflection that provides people with the capacity and willingness to examine local, global and intercultural matters, understanding and valuing global interdependencies, as well as different perspectives and views of the world, and establishing positive relations under conditions of equality and based on respect, with the aim of being transforming agents that seek social justice and a sustainable planet.

References

Abdallah-Pretceille, M. (2001). La educación intercultural. Idea Books.

Aguado,T. (2003). Pedagogía Intercultural. McGraw-Hill.

Aguado,T., (2009). El enfoque intercultural como metáfora de la diversidad en educación. En T. Aguado, y M. Del Olmo (Coords.), Educación intercultural: Perspectivas y propuestas (pp. 15-29). Ramón Areces.

Aguado, T., y Mata, P. (2017). Educación intercultural. UNED - Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. https://elibro-net.ubu-es.idm.oclc.org/es/ereader/ubu/115964?page=1

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

American Council on International Intercultural Education. (1996). Educating For The Global Community: A Framework For Community Colleges. https://stanleycenter.org/publications/archive/CC2.pdf

American Council on Education. (1998). Educating for Global Competence. America’s Passport to the Future. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED421940.pdf

Auld, E., & Morris, P. (2019). Science by streetlight and the OECD’s measure of global competence: A new yardstick for internationalisation? Policy Futures in Education, 17(6), 677-698. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205741419400302

Banks, J. A. (2014). Diversity, group identity, and citizenship education in a global age. Journal of Education, 194(3), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205741419400302

Barrows, et al. (1981). College students’ knowledge and beliefs: A survey of global understanding. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED215653

Bennet, M. J. (1986). Approach To Training. Intercatural Relations, 10, 179-196.

Boix-Mansilla, V., & Jackson, A. (2011). Educating for global competence: Preparing our youth to engage the world. Asia Society. https://asiasociety.org/files/book-globalcompetence.pdf

Boix Mansilla, V., & Wilson, D. (2020). What is Global Competence, and What Might it Look Like in Chinese Schools? Journal of Research in International Education, 19(1), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240920914089

Castejón, A., y Pàmies, J. (2018). Los agrupamientos escolares: expectativas, prácticas y experiencias. Tendencias Pedagógicas, 32, 49-64. https://doi.org/10.15366/tp2018.32.004

Comisión Europea (CE). (2006) Recomendación del parlamento europeo y del consejo de 18 de diciembre de 2006 sobre las competencias clave para el aprendizaje permanente (2006/962/CE) https://bit.ly/3fck4eT

Cornejo, M. J., y Gómez-Jarabo, I. (2018). Desarrollo de la competencia global en la formación del maestro. El caso de la asignatura Practicum. Innovación educativa, (28), 233-248. https://doi.org/10.15304/ie.28.5361

Curran, K. (n. d.). Global competencies that facilitate working effectively across cultures.

Cushner, K. (2011). Intercultural research in teacher education: An essential intersection in the preparation of globally competent teachers. Action in Teacher Education, 33(5-6), 601-614. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2011.627306

Deardorff, D. K. (Ed). (2009). Intercultural competence. SAGE Publications.

Delors, J. et al. (1996). La educación encierra un tesoro. Informe a la UNESCO de la Comisión Internacional sobre la educación para el siglo XXI. Santillana.

Deng, Z., & Luke, A. (2008). Subject Matter: Defining and Theorizing School Subjects. The SAGE handbook of curriculum and instruction, 66-87. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976572.n4

Doerr, N. M. (2020) ‘Global competence’ of minority immigrant students: hierarchy of experience and ideology of global competence in study abroad. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 41(1), 83-97. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2018.1462147

Engel, L. C., Rutkowski, D., & Thompson, G. (2019). Toward an international measure of global competence ? A critical look at the PISA 2018 framework. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 17(2), 117-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2019.1642183

García, M. E. (2008). La evaluación por competencias en la educación superior. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación Del Profesorado, 12(3), 1–16. https://bit.ly/352gK2h

García-Beltrán, E., Bueno, A., y Teba, E. (2019). Uso del modelo CCR en la investigación sobre competencia global. En Larragueta, M (coord), Educación y transformación social y cultural (pp. 361-380) Universitas. https://bit.ly/3naeFYe

Goren, H., & Yemini, M. (2017). Global citizenship education redefined–A systematic review of empirical studies on global citizenship education. International Journal of Educational Research, 82, 170-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.02.004

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health information & libraries journal, 26(2), 91-108.

Guirao Goris, Silamani J. A. (2015). Usefulness and types of literature review. Ene, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.4321/S1988-348X2015000200002

Grotlüschen, A. (2018). Global competence–Does the new OECD competence domain ignore the global South? Studies in the Education of Adults, 50(2), 185-202. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2018.1523100

Hajisoteriou, C., y Angelides, P. (2016). The Globalisation of Intercultural Education. The Politics of Macro-Micro Integration. Palgrave-Macmillan.

Hajisoteriou, C., & Angelides, P. (2020). Examining the nexus of globalisation and intercultural education: theorising the macro-micro integration process. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 18(2), 149-166. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2019.1693350

Hanvey, R. (1975). An Attainable Global Perspective. Center for Global Perspectives.

Heras, R., Vila, J., y Medir, R. M. (2019). Estrategias educativas para comprender y actuar en el mundo actual. Papeles de Trabajo Sobre Cultura, Educación y Desarrollo Humano, 15(3), 73–83. https://bit.ly/3mTkcm7

Hernández, R., Fernández, C., y Baptista, P. (2010). Metodología de la investigación. McGraw-Hill. 5ª ed.

Hunter, W. (2004). Knowledge, skills, attitudes, and experiences necessary to become globally competent. Tesis para doctorado. Lehigh University. https://bit.ly/38f2sNS

Hunter, B., White, G. P., & Godbey, G. C. (2006). What does it mean to be globally competent? Journal of Studies in International education, 10(3), 267-285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315306286930

Kim, J. J. (2019). Conceptualising global competence: situating cosmopolitan student identities within internationalising South Korean Universities. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 17(5), 622-637. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2019.1653755

Lambert, R. (1993). Educational Exchange and Global Competence. International Conference on Educational Exchange. Council on International Educational Exchange. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED368275.pdf

Leal, M. (2016). Dinámicas de identidad y educación intercultural en contextos urbanos. Opción, 32(11),787-807 https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/310/31048902046.pdf

Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional [MEFP] (2020). Informe español, versión preliminar. Competencia global PISA 2018. Secretaría General Técnica. https://bit.ly/3mVhpbT

Nordin, A., & Sundberg, D. (2016). Travelling concepts in national curriculum policy-making: the example of competencies. Educational Research Journal, 15(3), 314-328. https://doi.org/10.1177/j.jadohealth.2015.04.011

OCDE. (2005). The definition and selection of key competencies [Executive Summary] https://www.oecd.org/pisa/35070367.pdf

OCDE. (2014). PISA 2018 Framework plans: 38th meeting of the PISA governing board. Statistics, December, 1–13. https://bit.ly/3k1x5IQ

OCDE. (2018). Preparar a nuestros jóvenes para un mundo inclusivo y sostenible. PISA 2018 Marco de Competencia Global. Estudio PISA. https://bit.ly/3l3UNWb

Olson, C., & Kroeger, K. R. (2001). Global Competency and Intercultural Sensitivity. Journal of studies in international education, 5(2), 116-137. https://doi.org/10.1177/102831530152003

Ortiz-Revilla, J., Adúriz-Bravo, A., y Greca, I. M. (en prensa). Conceptualización de las competencias: Revisión sistemática de su investigación en educación primaria. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación Del Profesorado. https://bit.ly/3mX1Ctj

Parkhouse, H., Tichnor-Wagner, A., Cain, J. M., & Glazier, J. (2016). «You don’t have to travel the world»: accumulating experiences on the path toward globally competent teaching. Teaching Education, 27(3), 267-285. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2015.1118032

Reimers, F. (2010). Educating for Global Competency. En J. Cohen & M. Malin (Eds.), International perspectives on the goals of universal basic and secondary education. (pp.183-202). Routledge.

Sälzer, C., & Roczen, N. (2018). Assessing Global Competence in PISA 2018: Challenges and Approaches to Capturing a Complex Construct. International journal of development education and global learning, 10(1), 5-20. https://doi.org/10.18546/IJDEGL.10.1.02

Santander, P. (2011). Por qué y cómo hacer Análisis de Discurso. Cinta de Moebio, (41), 207-224. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-554X2011000200006

Schiro, M. S. (2013). Curriculum theory: conflicting visions and enduring concerns. Sage Publications.

Schmidt, V. A. (2015). Discursive institutionalism: understanding policy in context. In F. Frank Fischer, D. Torgerson, A. Durnovà, & M. Orsini (Eds.), Handbook of critical policy studies (pp. 187-205). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Tahirsylaj, A., & Sundberg, D. (2020). The unfinished business of defining competences for 21st century curricula—a systematic research review. Curriculum Perspectives, 40(2), 131-145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-020-00112-6

UNESCO. (2015). Declaración de Incheon para la Educación 2030. https://bit.ly/2IJkeyi

Wilson, M. S., & Dalton, M. A. (1997). Understanding the demands of leading in a global environment: A first step. Issues and Observations, 17(1/2), 12-14.

[1]. ‘Global’ is not synonymous with ‘general’, but rather with a contemporary phenomenon related to globalisation.

[2]. Education for sustainable development and global citizenship are fostered above all in the area of international cooperation for development by development NGOs and cooperation centres. The most developed intercultural education in the area of formal education focuses on educational inclusion in diversity settings.

[3]. In the 1960s, foreign students were already studying at US universities, while in Europe, this boom started towards the end of the 1980s with the Erasmus Programme.