ISSN: 1130-3743 - e-ISSN: 2386-5660

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.32183

ETHICS OF CARE: A THEORETICAL UNDERPINNING FOR RELATIONAL INCLUSIVITY

Ética de los cuidados: una base teórica para la inclusividad relacional

Christoforos MAMAS* and Carlos MALLÉN-LACAMBRA**

*University of California. San Diego. United States of America

**National Institute of Physical Education of Catalonia. Lleida. Spain.

cmamas@ucsd.edu; carlos.mallen@udl.cat

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5720-9794; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0620-5229

Date received: 06/10/2024

Date accepted: 13/01/2025

Online publication date: 02/06/2025

How to cite this article / Cómo citar este artículo: Mamas, C. & Mallén-Lacambra, C. (2025). Ethics of Care: A Theoretical Underpinning for Relational Inclusivity [Ética de los cuidados: una base teórica para la inclusividad relacional]. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 37(2), 99-124. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.32183

ABSTRACT

Inclusive education is a paramount objective of contemporary education, as an inclusive society becomes necessary to ensure democracy, justice and peace. However, current individualistic approaches often fail to address the relational nature of students and the need for adaptive and personalized learning. Relational inclusivity emerges as an innovative approach, shifting the focus from individual-centered models to a framework that emphasizes interconnectedness and supportive communities. This paradigm fosters responsive contexts that enhance academic performance, socioemotional and personal development. Relational inclusivity integrates social network analysis to evaluate social dynamics, enabling educators to take informed pedagogical decisions, after identifying key and marginalized students. Despite its wide practical application, relational inclusivity lacks a solid theoretical underpinning that highlights its educational importance and determines its pedagogical principles. The ethics of care, which reconceptualizes people as interdependent beings reliant on caring relationships, provides the necessary theoretical foundation. The objective of this study is to establish the philosophical and theoretical foundations of relational inclusivity based on the ethics of care, promoting an educational shift centered on interdependent relationships. This article employed a theory synthesis design to summarize and integrate the principles of relational inclusivity and the ethics of care into a solid framework. The educational dimension of the ethics of care complements and expands relational inclusivity by emphasizing the importance of nurturing caring relationships within educational contexts. This theoretical synthesis broadens the educational community's understanding of relational education, offering a more adaptive and interdependent approach suited to the complexities of human relationships.

Keywords: ethics of care; relational inclusivity; inclusive education; social network analysis; relationships.

RESUMEN

La educación inclusiva es un objetivo primordial de la educación contemporánea, una sociedad inclusiva es necesaria para garantizar la democracia, la justicia y la paz. Sin embargo, los enfoques individualistas actuales a menudo no logran abordar la naturaleza relacional de los estudiantes y la necesidad de un aprendizaje adaptativo y personalizado. La inclusividad relacional surge como un enfoque innovador, que desplaza el foco de modelos centrados en el individuo hacia un marco que enfatiza la interconexión y las comunidades de apoyo. Este paradigma fomenta contextos receptivos que mejoran el rendimiento académico, el desarrollo socioemocional y el personal. La inclusividad relacional integra el análisis de redes sociales para evaluar las dinámicas sociales, permitiendo a los educadores tomar decisiones pedagógicas informadas tras identificar a estudiantes clave y marginados. A pesar de su potencial práctico, la inclusividad relacional carece de un sustento pedagógico y filosófico sólido que respalde su relevancia. La ética de los cuidados, que reconceptualiza a las personas como seres interdependientes que dependen de relaciones de cuidado, proporciona la base teórica necesaria. El objetivo de este estudio es establecer los fundamentos filosóficos y teóricos de la inclusividad relacional basados en la ética del cuidado, promoviendo un cambio educativo centrado en relaciones interdependientes. Este artículo utilizó un diseño de síntesis teórica para resumir e integrar los principios de la inclusividad relacional y la ética de los cuidados en un marco sólido. La dimensión educativa de la ética de los cuidados complementa y amplía la inclusividad relacional al destacar la importancia de cultivar relaciones de cuidado en contextos educativos. Esta síntesis teórica amplía la comprensión de la comunidad educativa sobre la educación relacional, ofreciendo un enfoque más adaptativo e interdependiente adecuado a las complejidades de las relaciones humanas.

Palabras clave: ética de los cuidados; inclusividad relacional; educación inclusiva; análisis de redes sociales; relaciones.

1. INTRODUCTION

Inclusion is a fundamental right, rooted in the principles of equity and justice (UNESCO, 2022). As a universal right, education must inherently be inclusive, ensuring that no one is excluded from the opportunity to learn and grow (Shaeffer, 2019). Beyond promoting social justice by providing marginalized individuals with equitable opportunities, inclusive education is essential for fostering a political and social community where individuals learn not just for themselves, but for the benefit of society as a whole.

This perspective reinforces that inclusivity in education builds the foundations for more democratic, cohesive, and empathetic societies (Ryynänen & Nivala, 2017). This is aligned with the idea of care and community discussed by Vega-Solís et al. (2018), which emphasizes that collective education fosters not only individual growth but also the capacity for collective agency to transform oppressive structures. Education based on interdependence nurtures a collective power that challenges exclusion and marginalization, encouraging communities to act together toward shared goals. This idea highlights that inclusivity should not only aim to adapt marginalized groups into existing structures but to empower them and society collectively, enhancing their capacity to enact change.

Education that embraces diversity enriches the learning environment by adapting teaching methods to diverse learning needs, creating more engaging, effective, and supportive experiences for all students (Acedo, 2008). Moreover, it supports the socioemotional and personal development of students by fostering mutual respect and understanding among peers from different backgrounds, identities, talents and abilities, ensuring that every student feels valued and included (Mamas et al., 2019a). Ultimately, inclusive education strengthens society itself by cultivating positive interconnectedness and interdependence among individuals, creating a more just, cohesive, and equitable future (Rabjerg, 2017).

However, current models of inclusive education often fail to recognize the intrinsic interdependence of human beings by focusing on individualistic approaches, which overlook the relational nature of people. Human beings are not isolated entities; rather, they exist in a state of constant interdependence where their actions affect and are affected by others. As discussed by Vega-Solís et al. (2018), the notion of care and community reminds us that human beings thrive in communal structures where care is a shared responsibility. In focusing solely on individual needs, these models neglect how relationships influence the educational experience, either fostering or inhibiting growth, flourishing, or even harming others (Rabjerg, 2017). A failure to acknowledge this results in educational environments that are not fully inclusive, as they miss the opportunity to create relationally supportive and ethically grounded spaces that foster both personal and communal development. Inclusive education, therefore, must account for the positive aspects of interdependence, which allow for the flourishing of individuals through the mutual recognition and care that underpins ethical relationships (Rabjerg, 2017).

Relational inclusivity emerges as an alternative to overcome the limitations of current educational models by emphasizing the relational nature of human beings. This paradigm shift recognizes humans as interdependent entities, shaped by their relationships and structural and material conditions. Rather than centering education on the individual, relational inclusivity places relationships at the core, fostering an interconnected and supportive community. This approach values meaningful connections and diverse perspectives among students, educators, and stakeholders, creating an environment where everyone feels acknowledged and understood. By promoting responsive and inclusive environments, relational inclusivity not only enhances academic performance but also addresses personal needs, making it an ideal approach for improving inclusive education (Mauleón, 2020; Mamas et al., 2024; Mamas & Trautman, 2023).

Inclusive education necessitates ongoing professional development for educators, enhancing teaching quality and equipping them to address diversity effectively. Relational inclusivity supports this by proposing a Social Network Analysis (SNA) Toolkit to evaluate group dynamics, identify strengths and weaknesses, key persons, and marginalized members (Mamas et al., 2019b; Mamas et al., 2024). This approach provides a deeper understanding of how relationships influence students' behavior and learning, enabling educators to make informed pedagogical decisions that improve relational inclusivity. A common criticism of relational inclusivity and the use of SNA in education is their traditional focus on social capital approaches and lack of solid philosophical or pedagogical grounding. The ethics of care addresses these needs, providing a robust foundation for relational inclusivity. Ethics of care reconceptualizes people as interdependent relational entities who depend on mutual care for optimal living conditions (Busquets, 2019; Gilligan, 1982). By placing caring relationships at the core of education, the ethics of care effectively complements and strengthens the principles of relational inclusivity.

This article aims to explore the philosophical and theoretical foundations of relational inclusivity through the lens of the ethics of care. By combining these frameworks, it seeks to propose an educational approach that aligns with how we understand and relate to others. The article begins with an introduction to the theory of the ethics of care and its educational applications. It then delves into relational inclusivity, examines the use of social network analysis in education, and discusses educational strategies to improve relationships. Finally, it highlights how relational inclusivity, and the ethics of care intersect, emphasizing their connection.

2. METHODS

This article employed a theory synthesis design to integrate the principles of relational inclusivity and the ethics of care into a cohesive framework for inclusive education. Following the principles of theory synthesis (Jaakkola, 2020), the methodology consisted of two interconnected processes aimed at constructing this framework. The first process involved an extensive review of theoretical and empirical literature across disciplines such as education, sociology, ethics, and social network theory. This phase focused on summarizing foundational concepts by systematically analyzing and distilling the key elements of the ethics of care and relational inclusivity. It identified shared principles and critical distinctions, providing the theoretical foundation for integration.

The second process, integrating frameworks, synthesized overlapping themes into a unified perspective. This involved reconciling theoretical differences and aligning philosophical and practical dimensions to create a model that bridges ethics of care and relational inclusivity. This approach provides a comprehensive synthesis, addressing the fragmented understanding of care and inclusion in existing literature while offering actionable strategies for fostering inclusive and relationally supportive educational practices.

Through this structured approach, this theory synthesis bridges gaps in current literature, establishing the ethics of care as the foundation for relational inclusivity and offering a robust framework for inclusive education practices based on relationships and interdependence.

3. ETHICS OF CARE: A RELATIONAL ETHICS

All human beings live in a social context, meaning we are constantly involved in social relationships and communities that condition our lives. The ethics of care recognizes the interdependent nature of human beings, where our relationships are part of our identity; who we are, what we think, and how we act depend on the type of relationships we have with other living beings and our material and structural conditions (Camps, 2021; Gilligan, 1982). Living implies being dependent, to a greater or lesser extent, on our relationships, thus challenging the modernist idea of independence. Instead of considering human beings as independent individuals, the ethics of care reconceptualizes people as interdependent relational entities, shaped by each relationship (Busquets, 2019). Dependency, understood as a lack, incapacity, or diminishment in modern societies, loses its negative character and is redefined as an inherent aspect of being alive.

By reconceptualizing human beings as interdependent relational beings, care emerges as the fundamental ethical value (Camps, 2021; Gilligan, 1982). Care is defined as a proactive activity that encompasses everything we do to sustain, continue, and repair our "world"—our bodies, identities, and environment—to maintain life optimally (Tronto, 1998). All humans need care, so we live in a continuous interdependent relationship of care, providing and receiving care to live as best as possible with the different degrees of dependency we experience throughout our lives. The set of care relationships creates the care network, essential for ensuring people's freedom and well-being, especially for those in vulnerable situations (Camps, 2021; Held, 2006). From a substantive freedom perspective (Sen, 1999), positive care networks enhance the opportunities and capacities to promote well-being and to perform actions and achieve goals that a person values. Thus, the ability to reshape and cultivate positive care relationships facilitates people to coexist with their dependencies in the best possible way, improving substantive freedom and well-being.

Care practices support individuals in self-direction through an emancipatory approach, avoiding paternalism, even in situations of extreme vulnerability, and enabling them to collectively reshape social dynamics that perpetuate inequality and exclusion (Ryynänen & Nivala, 2017). This approach transcends individual empowerment, fostering a shared and transformative emancipatory process. The ethics of care emphasizes the importance of not only providing support but also actively giving voice and agency to marginalized individuals, encouraging them to participate in transforming the structures that oppress them (Busquets, 2019). By centering on collective emancipation, care practices enable communities to challenge and dismantle entrenched power relations, fostering a more inclusive and just society.

In conclusion, the ethics of care presents a paradigm shift, humans exist within social contexts that shape them and make them interdependent. By acknowledging this, the ethics of care highlights the vital role of care networks to address our dependencies and live optimally. These networks, rather than being an individual responsibility, embody a collective and communal commitment to sustaining life. In this way, care becomes the most fundamental pillar of our society that should guide our education (Vega-Solís et al., 2018).

4. ETHICS OF CARE APPLIED TO EDUCATION

An education based on the ethics of care implies a paradigm shift. This approach moves the focus from placing students at the center of learning to placing students' relationships at the heart of education, encompassing material conditions, structural conditions, and interactions with other living beings. The ethics of care emphasizes the importance of specific human relationships and the particular context of each situation (Mauleón, 2020). It prioritizes empathy, responsibility, and understanding of singular personal needs, over universal ethical principles and theoretical-legal responses based on formal standards grounded in rationality, objectivity, rigid logic, and common norms. Consequently, pedagogical decisions should be inherently partial and contextual, prioritizing specific needs over impartial decisions applied universally (Mauleón, 2020, Noddings, 1984; Vázquez-Verdera, 2009). An education based on the ethics of care approach must educate care and promote quality and dense care networks attending to specific needs and situations (Rabin & Smith, 2013). The goal should be to educate people to effectively participate in care relationships, fostering empathetic and supportive care networks that promote substantive freedom and well-being.

4.1. Educating care

An ethics of care education encompasses two essential dimensions: "caring for" and "caring about" (Noddings, 1984; Rabin & Smith, 2013; Vázquez-Verdera, 2009). "Caring for" involves direct, personalized actions of care between a caregiver and a care recipient, focusing on the interpersonal relationship and the commitment to the well-being of both parties. Key learnings for "caring for" include attentiveness, responsibility, competence, and responsiveness (Tronto, 1998). Attentiveness involves recognizing the needs of others through active perception and empathy. Responsibility entails accepting the obligation to respond to these needs with a commitment to act and evaluate one's abilities and resources to provide adequate and effective care. Competence requires having the knowledge and skills to provide effective care. Responsiveness emphasizes adjusting care based on the recipient's feedback to ensure it is truly personalized and effective.

Conversely, "caring about" refers to a more abstract concern for the well-being of others, encompassing persons, groups, or society (Noddings, 1984; Rabin & Smith, 2013). This care is not necessarily direct but involves attitudes of empathy and compassion that influence broader decisions and behaviors. Educating people to "care about" involves teaching solidarity, as Tronto (1998) suggests. This means creating a framework where persons' needs are valued, and collective care and community responsibility are emphasized. Solidarity involves recognizing interdependence, fostering a culture of care, promoting social justice to transform social structures and eliminate inequalities.

Integrating both "caring for" and "caring about" becomes crucial for comprehensive care education (Rabin & Smith, 2013; Vázquez-Verdera, 2009). While these concepts are different, they are interconnected and mutually reinforced. A general concern for others' well-being ("caring about") can motivate persons to engage in direct care actions ("caring for"). Conversely, experiences in "caring for" can deepen and reinforce the disposition of "caring about." Educating in both dimensions ensures a holistic approach to care that addresses immediate personal needs while also promoting broader societal empathy and support.

4.2. Teacher role

To educate “caring for” and “caring about”, Nel Noddings (1984) emphasizes that a teacher must focus on four key components: modeling, dialoguing, practicing, and confirming (Velasquez et al., 2013). Modeling involves teachers demonstrating care through respectful and considerate behavior, serving as role models for students. Dialoguing occurs when teachers and students engage in open, reflective discussions within a trusting environment, fostering critical reflections. Practicing provides students with opportunities to care for others, allowing them to experience the role of caregivers through group work and community service activities. Confirming helps students recognize and develop their best selves by understanding their desires, setting expectations, and providing effective feedback. Together, these components create a great educational environment to educate “caring for” and “caring about”.

Although this study approaches the teacher as a caregiver, it is equally important to emphasize and advocate for their role as care-receivers. While teachers nurture students with care, they also require robust care networks to sustain their well-being and enhance their professional capabilities. Institutions must critically reflect on the labor conditions of educators, who sell their labor to provide care, recognizing that their effectiveness depends on supportive structures addressing their physical, emotional, and professional needs (Cann et al., 2024). Research has increasingly focused on analyzing the caring networks of teachers to ensure their well-being and enhancing their professional capacities (Caduff et al., 2023). Additionally, a strong care network among students can alleviate the teacher’s workload by fostering peer-to-peer support, thereby reducing reliance on teachers to address some particular needs (Mamas et al., 2024).

4.3. School role

School context also plays a role for educating care. It is essential to build school environments on the expectation of honesty, openness, benevolence, and competence, ensuring that commitments are met in good faith (Vázquez-Verdera, 2009). In this sense, deeper and longer-lasting relationships help educators understand and meet students' needs. Trust becomes crucial, fostering reliability in long-term relationships and integrity in short-term ones. Creating a caring school environment involves engaging the entire community, including parents and educators, to establish safe and supportive contexts. A sense of belonging, commitment and community becomes crucial, especially for students with less strong care networks, ensuring that all students feel part of a supportive and caring community.

4.4. Enhancing care networks

Care actions are not general or impersonal; they are directed at specific persons with varying degrees of relationship or responsibility. In the ethics of care, the caregiver and care-recipient relationship become crucial, as stronger relationships foster a greater predisposition to care for that person (Lynch, 2007). These relationships can be instrumental, based on interests, or expressive, based on affectivity (Mamas & Trautman, 2023). Consequently, we tend to care more for those with whom we have stronger socio-affective bonds or from whom we gain something of interest. Therefore, an education based on the ethics of care must enhance interpersonal relationships to increase the willingness to care for others (Rabin & Smith, 2013).

Nel Noddings (1984) posits that our lives are embedded within affective relational ties that form care networks. She categorizes these networks into three concentric circles based on the intensity of socio-affective relationships: primary care relationships (love work), secondary care relationships (general care), and tertiary care relationships (solidarity work) (Lynch, 2007). Primary care relationships, exemplified by parent-child bonds, are characterized by strong attachment, intimacy, interdependence, intensity, and commitment. Secondary care relationships include relatives, friends, neighbors, and colleagues, where commitments are less intense. Tertiary care relationships involve unknown persons for whom care is given through legal or empathetic responsibilities. Noddings' categorization, while open to debate regarding the specifics of each category, underscores the varying intensities of socio-affective relationships and their impact on care. Therefore, education must enhance positive socio-affective relationships to foster care networks, improving the effectiveness and quality of care (Rabin & Smith, 2013).

According to ethics of care, education must foster a robust care network within the school, encompassing all members of the educational community: students, teachers, staff, families, and the wider community (Vázquez-Verdera, 2009). Promoting positive socio-affective relationships among these groups will enhance the overall care network. When students form positive affective bonds with their peers and educators, a supportive context for mutual care emerges (Mamas et al., 2019a). This environment facilitates both personal and academic support, establishing a foundation for a care network that can effectively address the needs of each member.

4.5. Summary

Education grounded in the ethics of care shifts the focus from individual to relational educational objectives, recognizing that students' well-being and learning are deeply rooted in their care networks. This approach highlights the importance of fostering both "caring for" and "caring about" to cultivate students who are attentive, responsible, competent, responsive, and solidary in their caring relationships. But also, teachers and schools play a pivotal role in cultivating care networks, enhancing caring relationships and creating inclusive and supportive environments for all.

To foster care, educators and schools need practical and effective strategies to establish and strengthen care networks. Relational inclusivity provides a comprehensive and actionable framework, equipping educational agents with powerful tools to evaluate care networks. It supports teachers in making informed pedagogical decisions and enables them to assess the impact of their interventions, ensuring the enhancement and sustainability of these essential relational structures.

5. RELATIONAL INCLUSIVITY

Relational inclusivity, within the context of the ethics of care, refers to the idea that education should extend beyond individual student-centered purposes to encompass the quality of relationships and the interconnectedness of students within a community or society (Mamas et al., 2024; Mamas & Trautman, 2023). The ethics of care provides a theoretical foundation for relational inclusivity, emphasizing the cultivation of meaningful connections and relationships of care within the context of inclusive education and education at large. This approach goes beyond mere acknowledgment of diversity and superficial inclusivity efforts by recognizing, valuing, and nurturing the diverse backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives of students, educators, and stakeholders. It actively works to create an environment where everyone feels seen, heard, and understood.

Relational inclusivity goes beyond the traditional educational focus on the teacher-student relationship, as emphasized in Nel Noddings' ethics of care. Instead, relational inclusivity innovatively promotes the fostering of "caring for" and “caring about” dynamics, primarily among peers. The theoretical underpinning for relational inclusivity in the ethics of care is grounded in several key principles (Vázquez-Verdera, 2009). First, the principle of interdependence highlights the importance of mutual care and support within relationships from a substantive freedom and social network perspective. Second, empathy and responsiveness in education must enhance people's sensitivity to the needs of others by listening and giving agency to diverse voices, acknowledging different experiences, and responding empathetically to the needs of all students. Third, contextual understanding requires for relational inclusivity and ethics of care to advocate for a shift in decision-making to a subjective and particular approach, acknowledging the significance of context in education and considering cultural, social, and personal contexts when designing and applying pedagogical strategies. Fourth, attentiveness to power dynamics and recognition of marginalized voices. Relational inclusivity and ethics of care actively work to address and rectify imbalances, promoting the recognition and inclusion of marginalized voices and perspectives to foster equitable education.

5.1. Relational inclusivity and social network analysis

In the context of relational inclusivity, Social Network Analysis (SNA) offers a powerful set of tools for understanding and enhancing the quality of relationships within educational environments (Borgatti et al., 2013). SNA allows for the visualization and analysis of the web of interactions among students, providing valuable insights into how these connections can be strengthened to promote a more inclusive and relationally supportive community (Mamas. & Trautman, 2023). SNA involves mapping social networks within a classroom/school, identifying who interacts with whom, and understanding the patterns of relationships. This mapping helps uncover key persons, clusters, and potential gaps in the network, revealing areas where students may be isolated or excluded (Mamas et al., 2019b). By identifying these areas, educators can target efforts to foster more inclusive relationships (Mamas et al., 2024).

Additionally, SNA highlights central figures in the network who influence social dynamics. Recognizing these key actors enables educators to leverage their influence to promote inclusivity and support initiatives aimed at fostering a caring environment. SNA also assesses the strength and quality of relationships by examining interaction frequency, trust, support, and reciprocity levels. This understanding is crucial for relational inclusivity, as it allows educators to focus on improving the quality of interactions to ensure they are meaningful and supportive. Moreover, SNA can uncover areas where certain groups or persons are marginalized or excluded, providing a clear picture of where interventions are needed (Mamas et al., 2024). Educators can design targeted strategies to integrate these marginalized persons or groups into the broader network, ensuring that everyone feels included and valued. By understanding existing social networks, educators can create opportunities for collaboration and support that align with the natural flow of relationships, enhancing the sense of community and mutual support.

SNA is also useful for monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of Relational Inclusivity initiatives. By periodically mapping and analyzing social networks, educators can track changes over time, assess the impact of interventions, and make data-driven decisions to continually improve inclusivity and supportiveness. In practice, SNA can be applied to examine different dimensions of Relational Inclusivity as well as other dimensions that the teacher may want to explore.

Incorporating SNA into the framework of relational inclusivity aligns with the principles of the ethics of care by providing a detailed understanding of the social relationships that shape the educational experience. This approach enables educators to design and implement strategies that foster a caring, inclusive, and supportive educational community where every student feels connected and valued.

5.2. Evaluation of social networks

Relational Inclusivity emphasizes evaluating the networks that teachers deem most relevant according to the characteristics of each group (Mamas et al., 2024). To support this process, the SNA Toolkit provides a flexible and adaptable tool for assessing relational dynamics, offering practical insights tailored to diverse contexts (Mamas et al., 2019b; Mamas & Huang, 2022; Mamas et al., 2024). While some caring practices remain invisible due to societal oversight or their intangible nature (Carmona-Gallego, 2023; Molinier, 2018), the toolkit can be complemented with qualitative or quantitative methods, such as interviews or questionnaires, to capture a fuller picture of caring networks. Relational inclusivity defends teacher empowerment by advocating for their autonomy in making context-specific relational questions. However, relational inclusivity also recommends the exploration of four key networks that shape students’ main experiences: friendship, recess, academic support, and emotional well-being (Mamas & Trautman, 2023).

- Friendship Networks: Analyzing friendship networks helps educators understand the social dynamics within the classroom. It reveals how students connect, who might be isolated, and the quality of peer interactions. By mapping out these networks, schools can identify students who need more support in forming positive relationships and create interventions to foster a more inclusive social environment.

- Recess Networks: Recess is a critical time for social interaction and physical activity. Observing and measuring interactions during recess can provide insights into students' social skills and peer relationships outside the structured classroom setting. It helps educators identify patterns of exclusion or bullying and develop strategies to ensure all students feel included and engaged during free play.

- Academic Support Networks: Academic support networks highlight how students seek and receive help from each other. Understanding these networks allows educators to see who students turn to for academic assistance. This can reveal gaps in support and guide the creation of more effective academic mentoring and support programs, ensuring that every student has access to the help they need.

- Emotional Well-being Networks: Emotional well-being is fundamental to a student's ability to learn and thrive. By mapping emotional support networks, educators can identify how students cope with stress, who they confide in, and the availability of emotional support within the school. This information is vital for developing programs that promote mental health, resilience, and a supportive school culture.

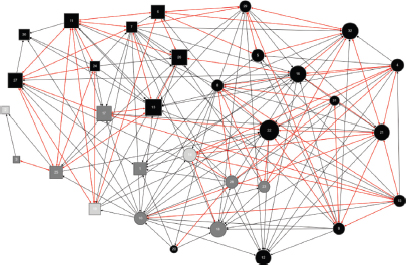

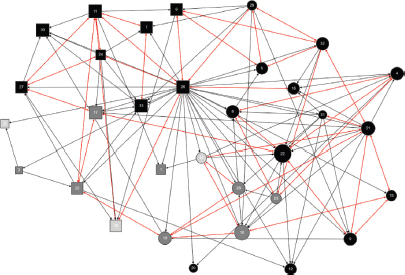

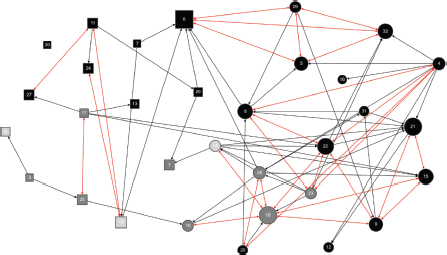

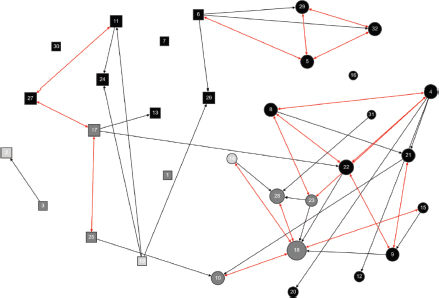

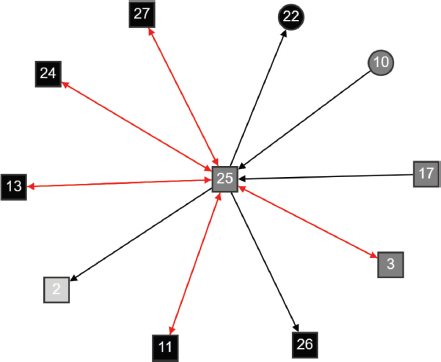

Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4, sociograms, present examples of the four networks in a class, illustrating the unique characteristics of each network and emphasizing the importance of analyzing diverse networks to address different relational objectives. Figure 5 depicts the egocentric friendship network of student 25, focusing solely on their direct relationships. The SNA Toolkit enables the analysis of both whole networks and ego networks, allowing teachers to assess not only the group's overall dynamics but also the individual situations of specific students. Additionally, the node (students) colors and shapes vary in each network to represent individual attributes, such as gender, race/ethnicity, SEND, frequency of absences, marks average, … This visualization enhances the analysis by showing how students with particular characteristics are distributed within the network, potentially revealing trends among specific population groups. These sociograms underscore the relational complexity of the group and highlight the educational potential of the SNA Toolkit.

FIGURE 1

SOCIOGRAM OF FRIENDSHIP NETWORK

Note: Squares = boys; circles = girls; black = not in sped program; dark grey = in sped program; light grey = exited sped program; arrowed line = unidirectional relationships; double arrowed line = reciprocated relationships

FIGURE 2

SOCIOGRAM OF RECESS NETWORK

Note: Squares = boys; circles = girls; black = not in sped program; dark grey = in sped program; light grey = exited sped program; arrowed line = unidirectional relationships; double arrowed line = reciprocated relationships

FIGURE 3

SOCIOGRAM OF ACADEMIC SUPPORT NETWORK

Note: Squares = boys; circles = girls; black = not in sped program; dark grey = in sped program; light grey = exited sped program; arrowed line = unidirectional relationships; double arrowed line = reciprocated relationships

FIGURE 4

SOCIOGRAM OF EMOTIONAL-WELLBEING NETWORK

Note: Squares = boys; circles = girls; black = not in sped program; dark grey = in sped program; light grey = exited sped program; arrowed line = unidirectional relationships; double arrowed line = reciprocated relationships

FIGURE 5

SOCIOGRAM OF THE FRIENDSHIP EGO NETWORK OF STUDENT 25

Note: Squares = boys; circles = girls; black = not in sped program; dark grey = in sped program; light grey = exited sped program; arrowed line = unidirectional relationships; double arrowed line = reciprocated relationships

Measuring relational inclusivity across context-specific networks provides schools with a comprehensive view of their community's social fabric. Systematically assessing interpersonal relationships, complemented by other methods, is essential for improving relationship quality within educational settings. This multidimensional approach ensures targeted interventions that foster environments where students feel valued and connected (Mamas et al., 2024). Relational inclusivity goes beyond recognizing the importance of relationships, as it actively promotes caring and inclusive educational contexts (Mauleón, 2020). A relational education requires evaluating the networks within the educational community and creating contexts that enhance these connections.

5.3. Educational strategies to improve relationships

As already stated, inclusive education has become a paramount objective in contemporary educational discourse, aiming to provide equitable learning opportunities for all students regardless of their backgrounds or abilities. However, current individualistic approaches often fail to capture the relational dynamics essential for fostering a truly inclusive environment. To address this gap, relational inclusivity, an innovative approach that emphasizes interconnectedness and supportive communities, offers a promising solution. By integrating SNA and grounded in the ethics of care, this approach seeks to enhance both academic performance and personal development through fostering meaningful relationships.

This section introduces a series of evidence-based educational strategies designed to promote relational inclusivity within the classroom. It should be noted that this is not an exhaustive list. These strategies, among others, include peer mentoring programs, collaborative learning projects, social network mapping, community-building circles, interdisciplinary workshops, social skill development sessions, reflective journals, inclusive events and celebrations, feedback and recognition systems, and buddy systems for new students. Each of these strategies is rooted in social network literature and supported by academic research, providing a robust framework for enhancing relational dynamics in educational settings.

To effectively implement these strategies, a Research-Practice Partnership (RPP) approach is recommended. RPPs bring together researchers and practitioners in a collaborative effort to address pressing educational challenges (Mamas & Trautman, 2023; Mamas et al., 2024). By leveraging the strengths and expertise of both parties, RPPs can ensure that the proposed strategies are not only theoretically sound but also practically viable and contextually relevant. This collaborative approach fosters continuous improvement, as ongoing feedback from practitioners informs research and leads to the refinement of educational practices (Mamas et al., 2024). In the following paragraphs, we briefly discuss each educational strategy.

To foster relationships in an educational setting grounded in social network literature, various activities and principles can be employed. These practical tips are designed to promote interconnectedness, enhance supportive communities, and create an inclusive learning environment. Establishing peer mentoring programs could present an effective strategy. Experienced students or those who exhibit leadership skills can be paired with newcomers or isolated students to provide guidance, share knowledge, and offer social support. This approach leverages the influence of central nodes (key persons) within the network to support integration and inclusion (Goodrich, 2018). Additionally, designing collaborative learning projects that require students to work together and draw on each other's strengths can significantly enhance social bonds (Johnson & Johnson, 2018). Rotating group members periodically ensures diverse interactions, facilitating the formation of both strong and weak ties, which enhances the network's cohesiveness and the flow of information.

Conducting social network mapping exercises, with tools like the SNA Toolkit, allows students to visually represent their social connections within the class (Mamas et al., 2019b). Educators can use these maps to identify isolated students and encourage more inclusive interactions, utilizing network analysis to integrate marginalized persons into the community (Borgatti et al., 2013; Mamas & Trautman, 2023; Mamas & Goldan, 2024). Organizing regular community-building circles where students share experiences, discuss challenges, and celebrate successes in a safe, supportive environment fosters a culture of trust and openness, reinforcing positive social norms and relational ties (Mamas et al., 2024).

Interdisciplinary workshops that bring together students from different academic backgrounds to work on common goals or projects encourage cross-boundary interactions, diversifying social networks and stimulating innovation through varied perspectives (Lave & Wenger, 1991). Conducting sessions focused on developing social skills such as empathy, active listening, and effective communication through role-playing and interactive activities equips students with the relational skills necessary to build and maintain positive, supportive relationships (Mamas et al., 2024).

Sportive games contribute to the development of social skills in students and promote diverse interactions while students feel wellbeing. Therefore, they represent an ideal context for improving interpersonal relationships and educating coexistence (Mallén-Lacambra et al., 2024). Maintaining age-appropriate reflective journals where students document their interactions, relationships, and personal growth, and periodically organizing sharing sessions to discuss insights, encourages self-awareness and reflection on social interactions, deepening relational understanding and personal development (Leinonen et al., 2016). Planning and hosting inclusive events and celebrations that reflect the diverse backgrounds and interests of the student body encourage participation and collaboration, using shared experiences to strengthen bonds and create a sense of belonging (Niemi & Hotulainen, 2016).

Implementing a system where students can give and receive positive feedback and recognition for their contributions to the community, both academically and socially, reinforces positive behaviors and relationships by recognizing and valuing students' efforts in building a supportive network (Skipper & Douglas, 2012). Finally, pairing new students with a buddy from the existing student body helps them acclimate, make connections, and feel welcomed, utilizing existing relationships to support newcomers and facilitate their integration into the network. This is particularly effective for students with disabilities (Alqahtani, 2015). By incorporating these activities and principles into educational practices, educators can foster a relationally inclusive environment that supports the academic and personal development of all students.

5.4. Summary

Relational inclusivity is a practical strategy to educate care, as it seeks to foster caring classrooms that enhance well-being, learning, and inclusion. Through the SNA Toolkit educators can map and evaluate key relational dynamics within their specific contexts, identify patterns within their classrooms, and implement targeted interventions to strengthen responsive groups. Moreover, relational inclusivity provides educators with actionable strategies, such as peer mentoring, collaborative projects and sportive games, empowering them to cultivate a caring and inclusive educational community.

6. DISCUSSION

This article underpins relational inclusivity through the ethics of care, demonstrating how both theories complement and reinforce each other. The ethics of care offers a robust pedagogical and philosophical framework that guides educators, while relational inclusivity translates these principles into actionable strategies, enabling teachers to implement the philosophical guidelines of the ethics of care in practical and impactful ways. This combination enhances the pedagogical significance of an inclusive education centered on relationships. Additionally, practical strategies are presented to help educators effectively implement relational inclusivity and the ethics of care in their daily practices.

6.1. Reconceptualizing inclusive education

Inclusive education has been a central goal of modern educational systems, but its approach has predominantly been individualistic and unidirectional, focusing on access and participation for each student separately, especially those in states of oppression or dependency (Shaeffer, 2019). However, the ethics of care and relational inclusivity provide a strong theoretical foundation for a new vision that emphasizes interdependence and relationships (Camps, 2021; Mamas et al., 2024). This paradigm shift invites us to see inclusion not just as access for marginalized individuals but as creating and maintaining a network of relationships that meet everyone's needs, shifting the focus from individuals to inclusive groups (Busquets, 2019; Mamas & Trautman, 2023). This rethinking of inclusive education goes beyond simply ensuring access for marginalized individuals; it views the role of education as emancipatory and transformative, fostering the collective agency needed to reshape oppressive structures in a way that emancipates all participants, not just adapting them to existing norms (Vega-Solís et al., 2018).

Integrating relational inclusivity with complementary theoretical perspectives, from the social capital theory (Dubos, 2017), relational inclusivity recognizes the value of networks and relationships in fostering trust, reciprocity, and shared norms, which collectively contribute to the social well-being and empowerment of marginalized students. Similarly, funds of knowledge theory (Esteban-Guitart & Moll, 2014) underscores the importance of valuing the cultural and experiential knowledge that students and their families bring to the classroom. When these two theories are integrated, they highlight how building strong relational networks within classrooms can leverage students’ diverse backgrounds as assets, promoting inclusive environments where both individual and collective strengths are celebrated and mobilized for shared success.

By integrating these complementary frameworks, relational inclusivity emphasizes the pivotal role of relationships in fostering supportive and responsive environments. However, achieving this vision requires attention not only to students' caring relationships but also to those of teachers. This approach underscores the necessity of equipping educators with adequate resources, training, and emotional support to sustain their caregiving roles effectively. Implementing policies to alleviate teacher burnout and stress is crucial for maintaining a high standard of care and attention in classrooms (Vázquez-Verdera, 2009). The ethics of care enriches relational inclusivity to ensure that all the educational actors receive the care they need, fostering a truly relational inclusive education.

6.2. Responsive environments

Responsive environments are conceptualized by the ethics of care as care networks and by relational inclusivity as positive student social networks (Mauleón, 2020; Lynch, 2007; Mamas et al., 2019a). The ethics of care focuses on care as the fundamental value for living an optimal life, defining care relationships as those relationships that sustain, continue and repair our “world” —our bodies, identities, and environment—to maintain life optimally (Held, 2006; Tronto, 1998). Relational inclusivity, by placing relationships at its core, reinforces the idea that genuine inclusion is achieved through interdependence, where both persons and communities flourish together (Ryynänen & Nivala, 2017). Relational inclusivity recognizes the multiplicity of social networks within a group. The teacher is encouraged to evaluate the most relevant context-based relationships for each group, highlighting the importance of the evaluation of four key networks: Friendship Networks, Recess Networks, Academic Support Networks, and Emotional Well-being Networks (Mamas & Trautman, 2023).

The multidimensional network approach of relational inclusivity ultimately aims to promote care among students, aligning with the ethics of care's perspective that we are interdependent beings whose well-being, development, and learning are enhanced by improving our relationships (Vázquez-Verdera, 2009; Tronto, 1998). The SNA Toolkit, a hallmark of relational inclusivity, allows for the evaluation of group relationships and the making of informed, specific pedagogical decisions tailored to the relational needs of each group and person (Borgatti et al., 2013). The SNA Toolkit precisely measures the intensity of relationships, which Noddings (1984) categorizes into three concentric circles based on the strength and commitment of each relationship. Periodic evaluation of relational intensity is crucial to understanding the evolution of relationships within each network type, with stronger relationships ensuring better care and responsiveness to person needs (Mauleón, 2020; Mamas et al., 2024; Noddings, 1984; Vázquez-Verdera, 2009).

When a classroom lacks responsiveness and care, relationships become fragmented, leading to social isolation and a diminished sense of belonging among students. Such deficiencies negatively affect students' well-being and learning, as positive relationships are crucial for their development and success (Tronto, 1998; Vázquez-Verdera, 2009). In these non-caring environments, marginalized students are particularly at risk of exclusion and disengagement, with the lack of support exacerbating existing inequalities and further hindering their education (Held, 2006; Ryynänen & Nivala, 2017). Moreover, without attentiveness to relational dynamics, educators may overlook opportunities to address interpersonal conflicts, bullying, or other relational issues. These unaddressed challenges can disrupt the educational environment and even harm students (Lynch, 2007; Mamas & Trautman, 2023).

Educators and students highlight the tangible benefits of relational inclusivity tools in fostering positive social networks. Many teachers have used the SNA Toolkit to explore relational dynamics in their classrooms, receiving overwhelmingly positive feedback from both educators and students. One teacher noted that ‘the SNA tool allows educators to collect data, make informed decisions and promote a culture of inclusivity.’ Another teacher mentioned that ‘it is important to promote a culture of inclusivity as it fosters a sense of connection and belonging among the students.’ Both teachers emphasize the role of the SNA Toolkit in promoting inclusivity in their classrooms. When students asked for their views on completing such surveys about their friendships and important connections via the SNA Toolkit, most of them provided positive feedback. One student said: ‘it is great that someone shows interest in our friendships. School is not only about learning’. Another student mentioned that ‘having friends at school is important because my friend stood up for me when I was bullied’. All in all, teachers and students see value towards examining and enhancing relational inclusivity.

6.3. Enhancing relationships

The ethics of care and relational inclusivity emphasize the critical importance of fostering interpersonal relationships to promote responsive environments. Relational inclusivity is supported by extensive empirical literature demonstrating effective educational strategies for improving various types of social networks (Mamas et al., 2024). Interpreting these strategies through the lens of the ethics of care helps us better understand their pedagogical and philosophical impact, showing how these practices educate caring for and caring about, enhancing the pedagogical relevance of relational inclusivity (Rabin & Smith, 2013; Vázquez-Verdera, 2009). By fostering caring relationships, we move beyond empowerment toward emancipation, recognizing that true inclusion is not just about enabling individuals but also about transforming systems to be responsive to diverse needs (Mauleón, 2020; Ryynänen & Nivala, 2017).

Relational inclusivity proposes concrete, practical educational strategies that align with Nel Noddings' concept of "practicing," helping educators provide students with opportunities to care for others through group work and community service activities (Noddings, 1984). While all practices can potentially improve various aspects that the ethics of care considers essential, the following strategies primarily develop key concepts of the ethics of care:

Peer mentoring programs (Goodrich, 2018), buddy systems (Alqahtani, 2015), inclusive events and celebrations (Niemi & Hotulainen, 2016), collaborative learning projects (Johnson & Johnson, 2018), and interdisciplinary workshops (Lave & Wenger, 1991) educate all dimensions of "caring for": attentiveness, responsibility, competence, and responsiveness. The first three focus more on affective networks, while the latter two, though starting from instrumental networks, can also enhance affective ties. Engaging in "caring for" in these contexts also fosters "caring about", sensitizing students to empathy and solidarity (Vázquez-Verdera, 2009).

Social network mapping (Mamas et al., 2019b) helps educators improve their attentiveness, responsibility, competence, and responsiveness by allowing periodic evaluations of their pedagogical strategies' impact. Community-building circles, reflective journals (Leinonen et al., 2016), and feedback and recognition systems (Skipper & Douglas, 2012) support Noddings' "dialoguing" and "confirming", while fostering empathy and solidarity, which enhances "caring about" and positively impacts "caring for." (Noddings, 1984).

The development of social skills through simulated situations such as: role playing, sportive games and theatrical activities can educate any aspect of the ethics of care if designed with specific approaches (Mallén-Lacambra at al., 2024; Mamas et al., 2024). These well-supported practices, along with teacher modeling—demonstrating care through respectful and considerate behavior—gain new dimensions through the ethics of care, highlighting their relational pedagogical potential.

Thus, both theories reinforce each other. Relational inclusivity helps the ethics of care by detailing the types of caring relationships within a group, providing empirical evidence for successful educational strategies that teach the principles of care-based education (Mamas et al., 2024). Conversely, the ethics of care enriches the interpretation of student social networks and effective learning situations, emphasizing the importance of educating in attentiveness, responsibility, competence, responsiveness, and solidarity (Tronto, 1998) to educate “caring for” and “caring about” (Vázquez-Verdera, 2009). This synergy enhances the pedagogical and philosophical significance of relational inclusivity practices, offering a deeper understanding of their impact on students and better focusing the desired educational outcomes. Additionally, the principles of "caring for" and "caring about" help evaluate the quality of student social networks, ensuring they foster care principles, whether instrumental or affective networks (Mamas & Trautman, 2023; Lynch, 2007).

Ultimately, both the ethics of care and relational inclusivity converge on the concept of "caring about." These theories assert that improving relationships is crucial, but there are also key values and competencies to be taught in relational education. Both emphasize the importance of sensitivity, empathy, and solidarity to enhance relational dynamics, improving individual relationships and fostering a greater willingness to care for those with whom we have weaker ties, within communities and societies (Camps, 2021; Mamas et al., 2024).

7. CONCLUSIONS

This article explored the philosophical and theoretical foundations of relational inclusivity through the lens of the ethics of care, providing a comprehensive framework for an educational approach centered on relationships. By integrating relational inclusivity with the ethics of care, this study shifts traditional paradigms focused on individual achievement, competition, and standardized testing—which prioritize academic success measured by grades and test scores—towards a relational paradigm emphasizing positive relationships. This new approach fosters responsive environments that enhance well-being, personal development, and learning, better aligning with the view of humans as interdependent relational entities rather than independent individuals. This critical innovative approach involves creating an environment where every student feels valued, understood, and supported, thereby fostering a strong sense of community within the classroom and the school.

Firstly, the ethics of care was introduced, and its educational applications were examined. This theory shifts our perspective from viewing humans as independent individuals to recognizing them as interdependent relational entities that require caring relationships to live optimally. This shift highlights the significance of enhancing relationships to promote responsive environments within educational settings.

Relational inclusivity was then explored, demonstrating how it complements and enhances the ethics of care by proposing a deeper evaluation of care relationships and group responsiveness. By using social network analysis (SNA), relational inclusivity provides tools to evaluate and improve the quality of relationships within educational environments. This approach helps educators identify group dynamics and key individuals, informing pedagogical decisions that foster a more inclusive and supportive community.

Practical educational strategies were discussed to illustrate how relational inclusivity can be effectively implemented, not only helping marginalized students but reshaping entire systems to be more relationally inclusive and just. This paradigm shift fosters not only personal growth but also collective societal transformation, where inclusive education becomes a shared responsibility (Ryynänen & Nivala, 2017). Strategies such as peer mentoring programs, collaborative learning projects, and sporting games were highlighted for their potential to enhance both "caring for" and "caring about" among students. These practices not only improve academic performance but also support the socioemotional and personal development of students, helping educators create a nurturing, responsive, and inclusive environment that enhances emancipatory educational practices.

The intersection of relational inclusivity and the ethics of care highlights their complementary nature, where each framework enriches the other. The ethics of care provides a robust philosophical foundation for relational inclusivity, while relational inclusivity offers practical tools and strategies to help educators implement the principles of the ethics of care in educational settings.

Underpinning relational inclusivity with the ethics of care calls for a holistic rethinking of our educational systems. Since humans are conceived as interdependent relational entities, our educational systems and inclusive practices must be adapted to our relational nature. This integrated approach aims to foster positive relationships and create supportive learning environments to benefit all members of the educational community. By embracing these principles, we can cultivate a more compassionate, effective, and inclusive educational system that meets the diverse needs of all students, ultimately contributing to the development of a just, cohesive, and equitable society.

FUNDING

We declare no conflicts of interest related to this research. This study was supported by the National Institute of Physical Education of Catalonia (INEFC) of the Generalitat de Catalunya and the University of Lleida (UdL), under Resolution 21/03/2022 and Order PRE/178/2021. The research was conducted as part of the project "Opportunity: Fostering Social Inclusion and Gender Equality in Formal and Non-Formal Educational Contexts through Traditional Sports and Games," co-funded by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union (Project Code: 622100-EPP-1-2020-1-ES-SPO-SCP).

REFERENCES

Acedo, C. (2008). Inclusive education: pushing the boundaries. Prospects 38, 5–13 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-008-9064-z

Alqahtani, R. (2015). High school peer buddy program: Impact on social and academic achievement for students with disabilities. European Journal of Educational Sciences, 2(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.19044/ejes.v2no1a1

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., & Johnson, J. C. (2013). Analyzing Social Networks. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Busquets, M. (2019). Discovering the importance of Ethics of Care. Folia humanística, 12. https://doi.org/10.30860/0053

Caduff, A., Lockton, M., Daly, A. J., & Rehm, M. (2023). Beyond sharing knowledge: Knowledge brokers’ strategies to build capacity in education systems. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 8(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-10-2022-0058

Camps, M. (2021). Time for care: another way of being in the world. Arpa editores.

Cann, R., Sinnema, C., Rodway, J., & Daly, A. J. (2024). What do we know about interventions to improve educator wellbeing? A systematic literature review. Journal of Educational Change, 25(2), 231–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-023-09490-w

Carmona-Gallego, D. (2023). Percepciones y prácticas de cuidado desde una dimensión ética. Revista Austral de Ciencias Sociales, 45, 241–261. https://doi.org/10.4206/rev.austral.cienc.soc.2023.n45-13

Dubos, R. (2017). Social capital: Theory and research. Routledge.

Esteban-Guitart, M., & Moll, L. C. (2014). Funds of identity: A new concept based on the funds of knowledge approach. Culture & psychology, 20(1), 31-48.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: psychological theory and women's development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Goodrich, A. (2018). Peer Mentoring and Peer Tutoring Among K–12 Students: A Literature Review. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 36(2), 13-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/8755123317708765

Held, V. (2006). The ethics of care: Personal, political, and global. Oxford University Press.

Jaakkola, E. (2020). Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. AMS Review, 10(1–2), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-020-00161-0

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2018). Cooperative learning: The foundation for active learning. Active learning—Beyond the future, 59-71. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.81086

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge university press.

Leinonen, T., Keune, A., Veermans, M., & Toikkanen, T. (2016). Mobile apps for reflection in learning: a design research in K‐12 education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(1), 184-202. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12224

Lynch, K. (2007). Love Labour as a Distinct and Non-Commodifiable Form of Care Labour. The Sociological Review, 55(3), 550–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2007.00714.x

Mallén-Lacambra, C., Pic, M., Lavega Burgués, P., & Ben-Chaabâne, Z. (2024). Educating gender equity through non-competitive cooperative motor games: Transforming stereotypes and socio-affective dynamics. Retos, 60, 498–508. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v60.107364

Mamas, C., Cohen, S.R., & Holtzman, C. (2024). Relational Inclusivity in the Elementary Classroom: A Teacher’s Guide to Supporting Student Friendships and Building Nurturing Communities (1st ed.). Routledge.

Mamas, C., Daly, A. J., & Schaelli, G. H. (2019a). Socially responsive classrooms for students with special educational needs and disabilities. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 23, 100334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.100334

Mamas, C., Daly, A. J., Struyve, C., Kaimi, I., & Michail, G. (2019b). Learning, friendship and social contexts: Introducing a social network analysis toolkit for socially responsive classrooms. International Journal of Educational Management, 33(6), 1255-1270. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-03-2018-0103

Mamas, C., & Goldan, J. (2024). Exploring the Social Networks of Highly Diverse Middle School Students with Disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2023.2239165

Mamas. C., & Huang, D. (2022). Social Network Analysis Software Packages. In Frey B. (editor) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation (2nd edition).

Mamas, C., & Trautman, D. (2023). Leading Towards Relational Inclusivity for Students Identified as Having Special Educational Needs and Disabilities. In Daly, A. J., Liou, Y.H. (Eds.), The Relational Leader: Catalyzing Social Networks for Educational Change. Bloomsbury.

Mauleón, X. E. (2020). Dependientes, vulnerables, capaces, receptividad y vida ética. Los libros de la Catarata.

Molinier, P (2018). El cuidado puesto a prueba por el trabajo. Vulnerabilidades cruzadas y saber-hacer discretos, In Gutiérrez, D. (Eds.), El trabajo de cuidado (pp. 191-214). Fundación Mediafé.

Niemi, P. M., & Hotulainen, R. (2016). Enhancing students’ sense of belonging through school celebrations: A study in Finnish lower-secondary schools. International Journal of Research Studies in Education, 5(2), 43-58. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrse.2015.1197

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education. University of California Press.

Rabin, C., & Smith, G. (2013). Teaching care ethics: Conceptual understandings and stories for learning. Journal of Moral Education, 42(2), 164–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2013.785942

Rabjerg, B. (2017). An analysis of human interdependent existence. Res Cogitans, 12(1), 93-110. https://doi.org/10.7146/rc.1296646

Ryynänen, S., & Nivala, E. (2017). Empowerment or emancipation? Interpretations from Finland and beyond. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 33-46. https://doi.org/10.SE7179/PSRI_2017.30.03

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Knopf.

Shaeffer, S. (2019). Inclusive education: a prerequisite for equity and social justice. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. 20, 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-019-09598-w

Skipper, Y., & Douglas, K. (2012). Is no praise good praise? Effects of positive feedback on children's and university students’ responses to subsequent failures. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(2), 327-339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02028.x

Tronto, J. C. (1998). An ethic of care. Generations-Journal of the American Society on Aging, 22(3), 15–20.

UNESCO (2022). Reimagining our futures together: A new social contract for education. Unesco; SM foundation.

Vázquez-Verdera, V. (2009). Education and the Ethics of Care in the thought of Nel Noddings. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Valencia]. RODERIC https://roderic.uv.es/items/1ba4c7c4-0a42-4df3-8a35-f911bffcc203

Vega-Solís, C. Martínez-Buján, R., & Paredes-Chauca, M. (2018). Cuidado, comunidad y común. Extracciones, apropiaciones y sostenimiento de la vida. Traficantes De Sueños Útil.

Velasquez, A., West, R., Graham, C., & Osguthorpe, R. (2013). Developing caring relationships in schools: A review of the research on caring and nurturing pedagogies. Review of Education, 1(2), 162–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3014