ISSN: 1130-3743 - e-ISSN: 2386-5660

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.32145

DIGITAL ALTERITY IN SCHOOL: ADOLESCENTS AND SOCIAL NETWORKS

Alteridad digital en la escuela: adolescentes y redes sociales

Sandra Gisela MARTÍN-MARTÍNEZ & Carola GÓMEZ

Universidad Antonio Nariño. Colombia.

smartin80@uan.edu.co; cagomez14@uan.edu.co

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4210-2799; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5003-938X

Date received: 01/09/2024

Date accepted: 01/12/2024

Online publication date: 01/07/2025

How to cite this article / Cómo citar este artículo: Martín-Martínez, S. G. & Gómez, C. (2025). Digital Alterity in School: Adolescents and Social Networks [Alteridad digital en la escuela: adolescentes y redes sociales]. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 37(2), 1-23, early access. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.32145

ABSTRACT

Virtual social networks are crucial spaces for adolescent interaction, where relationships are forged that reinforce or extend existing face-to-face social connections. The present study aims to expand the existing frameworks of youth representation at school by analyzing how adolescents build relationships of alterity in virtual social networks. A qualitative approach to virtual ethnographic design was employed, whereby participant observation was conducted on digital platforms (Instagram and Facebook) throughout the year 2023. Additionally, focus groups and semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 students between the ages of 16 and 18 enrolled in two public educational institutions in Colombia and Spain. The data were organized using ATLAS. ti 24 with an open coding process, with the concepts of virtual social networks and digital alterity serving as analytical categories. The findings indicate that participants form relationships in virtual social networks based on specific uses and motivations by deploying socioemotional skills oriented towards the care of others. Therefore, social networks are becoming spaces where adolescents gain recognition from their peers, express their personalities freely, strengthen existing friendships, form new social bonds, and shape their digital identities. In light of the increasing prevalence of these platforms during adolescence, contemporary society has sought to address the issue of cyberbullying. However, it is imperative to implement school coexistence programs that provide students with continuous training strategies in socio-emotional development to foster the establishment of relationships of digital alterity characterized by recognition of the other, their fragility, and their radical difference.

Keywords: virtual ethnography; virtual social networks; digital alterity; adolescence; education.

RESUMEN

Las redes sociales virtuales son espacios de interacción esenciales durante la adolescencia, en los cuales se construyen relaciones que complementan o extienden los lazos sociales presenciales. El presente estudio busca ampliar los marcos de representación de lo juvenil en la escuela a través del análisis de la forma en que los adolescentes construyen relaciones de alteridad en las redes sociales virtuales. Con un enfoque cualitativo de diseño etnográfico virtual, se realizó observación participante en plataformas digitales (Instagram y Facebook) durante el año 2023, y se empleó el grupo focal y la entrevista semiestructurada con 20 estudiantes entre los 16 y 18 años pertenecientes a dos instituciones de educación pública de Colombia y España. Los datos se sistematizaron en ATLAS.ti 24 con un proceso de codificación abierta y con los conceptos de redes sociales virtuales y alteridad digital como categorías de análisis. Los resultados muestran que los participantes establecen relaciones en las redes sociales virtuales basadas en usos y motivaciones particulares a través de un despliegue de habilidades socioemocionales orientadas al cuidado del otro. Así, las redes sociales se consolidan como espacios donde los adolescentes obtienen el reconocimiento de sus pares, expresan libremente su personalidad, fortalecen lazos de amistad, construyen nuevos vínculos sociales y configuran su identidad digital. Ante el creciente uso de estas plataformas durante la adolescencia, la respuesta de la sociedad contemporánea ha sido prevenir el ciberacoso. No obstante, se requiere implementar programas de convivencia escolar que brinden a los estudiantes estrategias de formación continua en el desarrollo socioemocional para fomentar el establecimiento de relaciones de alteridad digital caracterizadas por el reconocimiento del otro, de su fragilidad y de su radical diferencia.

Palabras clave: etnografía virtual; redes sociales virtuales; alteridad digital; adolescencia; educación.

1. Introduction

Virtual social networks (VSNs) as spaces for socialization represent a significant area of research interest. Indeed, since the official launch of the social network Facebook in 2005, the number of studies published about the experiences of using social networks has grown exponentially (Pertegal-Vega et al., 2019).

A substantial body of research has examined the potential risks associated with using VSNs among adolescents (Popat & Tarrant, 2023). One illustrative example is the promotion of appearance culture and the pressure to comply with beauty standards that are prevalent on digital platforms. This significant factor increases adolescents’ vulnerability and negatively affects their identity construction (Demaria et al., 2024; Hoxhaj et al., 2023). Such dynamics have been linked to an increased risk of depression and suicidal tendencies (Biernesser et al., 2020). Nevertheless, strategies such as parental mediation, which are based on dialogue and joint participation in the use of social networks, have been demonstrated to be practical tools for mitigating these risks (Fam et al., 2022).

These types of strategies demonstrate that, in this novel context of human interaction, we are also obliged to assume responsibility for others, both for those who are within our field of vision and for those who remain obscured (Ure, 2017), as Lévinas termed it, ‘alterity’ (Lévinas, 2001). The author posits that alterity entails a sense of responsibility and hospitality towards others, irrespective of race, religion, or ideology (Lévinas, 2001). The concept of alterity in the context of VSNs is characterized by specific ethical considerations, including respecting others, promoting care for others, and fostering cyber coexistence (Khatod, 2024; Zych et al., 2018).

Nevertheless, studying othering in digital scenarios remains a field in its infancy. Notable research has concentrated on the examination of challenges to cyber coexistence among adolescents (Fernández-Montalvo et al., 2015; Romera et al., 2021; Zych et al., 2018), with less attention devoted to the prospects for recognition and care of the other in VSNs. In contrast, authors such as Hill (2011) and Ure (2017) encourage reflection on the novel relationships formed in digital platforms and the recognition that, despite the use of the body to interact, there is also a willingness to care for the other as a distinct form of experiencing alterity in the digital context.

Furthermore, in addition to advancing theoretical reflection on alterity in the digital context, it is necessary to develop research that provides empirical evidence to contribute to understanding this subject of study. Consequently, this research aims to extend the conceptual frameworks that represent the adolescent in an educational context by analyzing how adolescents construct relationships of alterity in VSNs. The conceptual contributions of this research highlight the necessity for creating educational and convivial experiences that recognize and accommodate contemporary adolescents and how they construct relationships with others in digital spaces.

Next, the proposed objective is sought to be achieved by exposing the methodological design that guided the research. Subsequently, the analysis and discussion of results based on the triangulation of information are presented. The analysis begins with an argument for the relevance of VSNs as spaces for social interaction during adolescence. It then presents how adolescents construct relationships of alterity in different VSNs. In conclusion, it is imperative to develop digital training strategies for students founded upon the principles of alterity, care for the other, and recognition of their radical differences.

2. Methodology

The present research employs a qualitative approach based on virtual ethnography and the established methods of this approach. Ethnography is the study of the practices and relationships of a culture, the meanings ascribed to them by the participants, and the interpretations offered by the researcher (Restrepo, 2016). The field of work for this research is not necessarily constituted in a geographically located space (Hine, 2004a Marcus, 2018). Instead, it is situated in a virtual setting, which is appropriate given the nature of the phenomenon under study, namely digital alterity.

The study involved the participation of twenty adolescents aged between 16 and 18 from Colombia and Spain. Ten participants were from a public educational institution located in the southwestern region of Bogotá, Colombia, while the remaining ten were from a public educational institution in Santaella, Spain. The participants granted permission for the use of their information by signing informed consent forms that emphasized the voluntary nature of their participation, the confidentiality of the information provided, and the exclusive academic use of the data collected.

Participant observation was employed in virtual settings on the social media platforms Instagram and Facebook between April 2023 and December 2023 as part of conducting the virtual ethnography. Although the researcher’s presence in the interaction scenario may influence the participants’ behavior, this method allowed the researcher to establish a relationship of trust with the participants, a characteristic inherent to classical ethnography conducted in face-to-face contexts (Ardèvol et al., 2003).

Furthermore, focus groups and semi-structured interviews were conducted. As posited by Benavides-Lara et al. (2022), focus groups facilitate the construction of meaning by participants through dialogue and narrative. The semi-structured interview is conversational, establishing a trust bond between the researcher and the interviewee. Additionally, its contextual nature contributes to constructing a relationship of proximity between them (Flick, 2015). The data were organized and analyzed using the ATLAS.ti 24 software. An open coding process was conducted, and subsequently, research categories were established to facilitate the interpretation of the data in the context of the digital alterity theory.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Virtual social networks: digital interaction spaces

Over the past two decades, there has been a notable increase in the prevalence of virtual social networks (VSNs) within the digital domain (Van Dijck, 2016). These social interaction platforms facilitate the strengthening of existing friendships and the formation of new relational ties between users who may be located in geographically distant places (Andrade-Vargas et al., 2021). Adolescents are a significant demographic of VSNs users, leading to increased research interest in identifying their use types and developing predictive algorithms to understand their preferences (Gil-Ruiz & Hernández-Herrera, 2023). These algorithms direct the generation of tailored digital content, ultimately shaping younger users’ preferences and inclinations (Gil-Quintana & Amoros, 2020).

VSNs can be characterized as digital spaces for interaction in adolescence based on students’ uses of these platforms, their motivations for using them, and the socio-emotional skills they use. Because VSNs represent a crucial arena for social interaction, educational institutions must integrate cross-cutting educational experiences about the responsible and ethical utilization of VSNs.

3.1.1. Uses of VSNs

Adolescents engage in VSNs to interact with others, maintain regular contact with their friends, expand their social circle, and entertain themselves by creating or accessing digital content related to their interests (Bucknell Bossen & Kottasz, 2020; Pertegal-Vega et al., 2019). In terms of the utilization of VSNs as a source of entertainment, one student articulated that in such contexts, they seek to observe the activities of their acquaintances and engage in self-entertainment, citing the consumption of humorous videos and the acquisition of novel information as key motivations (Source: Focus group in Spain, 2023). For other participants, it is essential to visualize content that aligns with their preferences and interests:

I like Facebook because of its content—sometimes the memes are funny, and so on—and Instagram because of the content they upload; I love the content more because it is very much related to what I like, such as the arts and drawing (source: focus group in Colombia, 203)

In addition to being entertainment spaces for adolescents, VSNs facilitate strengthening relationships with friends and family (Murciano-Hueso et al., 2022). The authors assert that VSNs have become the most popular venues for adolescents to socialize with their peers. According to data from the Statista portal, the social network with the most active users globally is Facebook, which has approximately four billion users. Subsequently, YouTube, Instagram, WhatsApp, and TikTok are the following most popular platforms, each with over one billion monthly active users (Statista, 2024). Similarly, the analysis of the focus groups and semi-structured interviews indicates that the participants’ most frequently used social media platforms are TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, and WhatsApp (Figure 1).

Figure 1

VSNs preferred in adolescence

Source: Own elaboration

The participants of the focus groups and interviews considered WhatsApp to be a social network. They stated that this application allows them to interact frequently with their friends and family through individual or group chat. WhatsApp is the platform where users engage in most of their communication with friends and family, often through groups that include both. The following comment illustrates how friendship bonds are reinforced within the WhatsApp context. (Source: focus group in Spain, 2023):

So, it was like encouraging this union through the WhatsApp group, for example, yesterday we had free time in the afternoon, we all started to play, and they took videos and laughed and sent the videos to the group. (source: semi-structured interview in Colombia, 2023)

Moreover, VSNs are a means of maintaining social contact with significant people in our lives who are geographically distant (Ellison et al., 2007; Marciano et al., 2022; Reyero et al., 2021). For example, a student stated, “It is true that networks also unite you with the family that is not there and unite you with the people you have far away” (source: focus group in Spain, 2023). Similarly, another student emphasized that “networks are a means of communication with other people when they are at a distance, as they can hardly see each other, so it is possible through these applications” (source: focus group in Colombia, 2023).

Consequently, the distinction between face-to-face and digital interactions is becoming increasingly blurred, giving rise to a hybrid space of communication (Machado, 2017; Murciano-Hueso et al., 2022). Therefore, actions that are currently routine for adolescents, such as creating or viewing online content on VSNs, are as crucial in forming relationships with others as actions that occur in offline or face-to-face life. As Sari et al. (2020) have observed, in this era of disruption, schools must provide adolescents with the formative elements they need to use VSNs in a prosocial manner.

3.1.2. Motivations for participation in the VSNs

During adolescence, “performative tendencies fuel the pursuit of an effect: recognition in the eyes of others and, above all, the coveted trophy of being seen” (Sibilia, 2008, p. 130). Bucknell Bossen and Kottasz (2020) posit that adolescent girls utilize TikTok to showcase their musical and dance abilities to gain social recognition. The following examples illustrate how adolescent girls utilize this social network to gain visibility and recognition from others. In a semi-structured interview conducted in Colombia in 2023, one participant stated, “On TikTok, I occasionally post videos of myself performing in a sexually attractive manner.” Similarly, in a focus group held in Spain in the same year, another participant said, “On TikTok, I have a dance that I performed with my friends in a playful and carefree manner.”

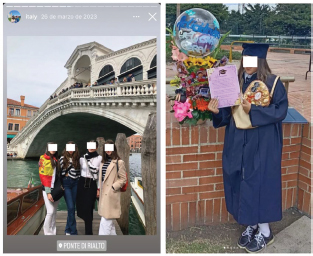

One of the key motivations for adolescents to engage in VSNs is to publish images of events that are significant in their lives and that they believe to be worthy of social recognition (Figure 2). In the current era, human relationships are increasingly mediated by various forms of social media. Socialization has shifted beyond the traditional face-to-face context, with the exchange of information, photographs, and memes playing a significant role in VSNs (Mateus et al., 2022). Figure 2 illustrates how participants utilize the platform to share images of significant moments with friends, trips, and academic achievements, aiming to elicit recognition from their followers in the VSNs.

Figure 2

Mediatized interactions

Source: Digital field journal

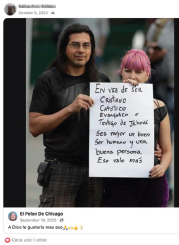

In addition to seeking social recognition through display strategies, adolescents are motivated to use VSNs because they interact with lower social inhibition on these platforms (García-Ruiz et al., 2018; Gómez-Baya et al., 2019). As Portillo Fernández (2016) notes, in the performance plane of VSNs, adolescents can express their ideologies and opinions regarding various social phenomena without the fear of censorship that would otherwise be present in face-to-face interactions. “I feel more confident expressing myself on the networks; in person, it is more challenging for me” (source: focus group in Colombia, 2023). In a photograph shared by a student on an Instagram story, the subject openly declares her religious beliefs (Figure 3). In contrast, a meme shared on another student’s Facebook wall represents her disagreement with certain religious practices (Figure 4).

Figure 3

Expression of religious beliefs

Source: Digital field journal

Figure 4

Critical stances towards religion

Caption: “Instead of being a Christian, Catholic, Evangelical or Jehovah’s Witness, be better, be a good human being and a good person. That is more valuable”.

Source: Digital field journal

According to Sibilia (2008), personality is created and recreated in VSNs through publications that attract followers’ attention. This is reflected in the data analysis of this study, which, in this sense, shows that the primary motivation of adolescents to participate in VSNs is the search for recognition and visibility in different communities, mainly through social display mechanisms. As exposed by García-Ruiz et al. (2018), schools are called to understand students’ motivations to be part of VSNs and to integrate them in didactic proposals that contribute to the academic and convivial spheres.

3.1.3. Social-emotional skills in VSNs

Ethical conduct in the context of VSNs necessitates the deployment of socioemotional competencies. For instance, emotional independence enables individuals to care for themselves and safeguard themselves from social rejection (Piccerillo & Digennaro, 2024). Most of the participants have developed emotional independence skills by not allowing negative opinions or the absence of reactions to their publications to affect them; an example of this is the following intervention: “I know how to take care of myself, and I know how to value myself, not having to depend on any likes, any comments” (source: semi-structured interview in Colombia, 2023). They also try to be self-confident when they post on VSNs: “I have nothing to hide, so I do not care if someone else sees what I post” (source: focus group in Spain, 2023).

In contrast, emotional regulation is defined as the capacity to contemplate the potential impact of one’s actions on the emotional state of others (Granados et al., 2020). One participant note that it is important to consider whether the content to be shared in the VSNs may or may not hurt her peers: “I try not to be offensive to the thoughts of others or to their opinions” (source: focus group in Colombia, 2023).

As for impulsivity control, this skill demonstrates the ability of adolescents to avoid reacting immediately to the publications of others and that sometimes they may differ from their points of view (Cebollero-Salinas et al., 2022). In this sense, participants are impulsive when commenting or reacting in VSNS: “I say what I think about things, and then I give my opinion; I do not invent things to please certain types of people” (source: focus group in Spain, 2023). In addition, they tend to seek explanations for posts that make them uncomfortable: “It happens to me mainly in WhatsApp groups, and when they make comments that I do not like towards others, I tend to ask the reason for the comments” (source: focus group in Colombia, 2023).

Thus, emotional independence, emotional regulation, and impulsivity control are skills that generate prosocial behaviors oriented toward caring for others (Cebollero-Salinas et al., 2022). As stated by Marín-López et al. (2020), educating at school to favor the development of socioemotional skills contributes to constructing and improving interpersonal relationships in face-to-face and digital environments.

As previously stated, the evidence presented in this section demonstrates the crucial role of VSNs as adolescent interaction spaces. In these digital environments, they encounter opportunities for entertainment and reinforcing interpersonal bonds. Furthermore, our findings indicate that the primary motivations for use are the desire to gain recognition from their peers and to express their personality freely. In conclusion, we identified the way in which students employ a set of specific socio-emotional skills that they adapt to relate to others in the VSNs.

In light of the evolving challenges posed by the advent of the digital age in adolescence, schools are compelled to expand their comprehension of the dynamics of student relationships to encompass the VSNs context and provide students with the necessary opportunities to educate themselves in an ethical use of these scenarios, oriented towards respect and care for others.

3.2. Alterity in digital scenarios: recognition of the other in VSNs

As Lévinas (2001) asserts, the experience of alterity in human relations is antithetical to any form of violence against the other and to any attempt to dominate or deny the other the recognition of his or her radical difference. In contrast, the author suggests that alterity represents an ethical experience of the relationship with the other, who challenges us through their condition of vulnerability, prompting a response and the provision of care in the immediacy of the encounter. Furthermore, digital platforms give us the unavoidable obligation to assume responsibility for others, even when the contact is purely digital (Ure, 2017).

In the absence of the body in digital interactions, virtual social networks (VSNs) offer a variety of interaction elements on their platforms that can be utilized to foster proximity. Consequently, the utilization of chat conversations, comments on posts, reactions with emojis, and the publication of images are indicative of the presence of the other in virtual social networks (VSNs). Similarly, the specific applications of these resources facilitate the configuration of identities and the representation of emotional states that encourage the recognition of the other on each platform (Hill, 2011). In light of these considerations, raising the relationship of alterity in the digital scenario implies considering that encountering the needs or suffering of the other is an ethical event that is generated thanks to a virtual proximity characteristic of the VSNs (Ure, 2017).

3.2.1. Caring for each other in VSNs

According to Lévinas (1974; 2001), we face the unavoidable call to be responsible for the other in the relationships we establish. Nevertheless, his thesis was developed in an environment where the VSNs were not established as social interaction scenarios. Given the emergence of VSNs as new arenas for adolescent socialization, we are called to understand the particular forms of relationships with each other in such scenarios (Serres, 2013).

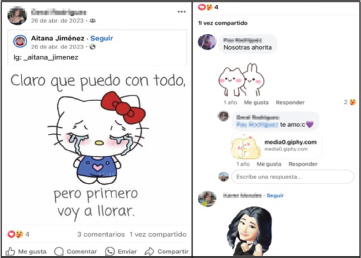

In this regard, the study participants illustrate how responsibility towards the other manifests in the VSNs through the care they provide, which can be observed in digital interactions. Adolescents demonstrate their interest in responding to and accompanying others who suffer through comments, GIFs, emojis, and avatars expressing empathy and solidarity (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Care of the other in VSNs

Caption left image: “Of course I can handle anything, but first I’m going to cry.” Caption right image: “Us right now” “I love you”.

Source: Digital field journal

Caring for those who show themselves vulnerable is a way of responding to their needs or the suffering they experience (Jaramillo Ocampo et al., 2018). As a form of caring for the other in VSNS, adolescents try not to hurt their peers, as well as some students expose: “I take care of others trying not to be offensive in front of others’ thoughts or front of their opinions, I always try to respect the things that others think” (source: semi-structured interview in Colombia, 2023). In addition, “one can publish and comment, but the important thing is to try to make sure that the comments one makes to others do not hurt anyone” (source: focus group in Colombia, 2023).

As Hill (2011) notes, a distinctive aspect of the interaction process in VSNs is the creation of digital proximity with others by utilizing resources inherent to these relationship spaces. As the author illustrates, according to Levinasian theory, proximity is generated because one has the physical presence of the other and is constructed using a gesture or affectionate expression. In contrast, in VSNs, adolescents utilize other forms of expression, such as comments and reactions, to establish proximity. These resources facilitate adolescents’ ability to establish proximity with others and express their willingness to offer solidarity with those who express their struggles through memes.

In the digital space, the individual is not isolated; their actions prompt them to respond to the various forms of the other’s call (Ure, 2017). For instance, Instagram allows the creation of stories that prompt others to respond. The use of stickers, such as “Your turn,” “Questions,” “Survey,” and “Questionnaire,” fosters a sense of digital proximity and a desire to engage with the other. Consequently, the stories created with the sticker “Your Turn” are distinguished by their appellative function, which solicits responses and reveals aspects of one’s life. This prompts the creation of new stories involving numerous individuals to provide a response and generate novel forms of relationships of alterity.

An ethical event occurs due to the encounter when the other is revealed and extends an invitation for us to embrace him or her (Jaramillo Ocampo et al., 2018). In the digital domain, the other presents themselves and discloses their distinctive characteristics, awaiting acceptance and welcome. An illustrative example is that of adolescents who possess a gender identity that differs from that of the majority of their peers. In such cases, VSNs serve as a platform for these adolescents to present their distinctiveness and interact with others who share similar life experiences (Healy, 2021). As illustrated in Figure 6, the contacts of a participant express their welcome through reactions that convey affection and approval.

Figure 6

Recognition of the difference

Caption: “Life’s too short to pretend you’re straight.”

Source: Digital field journal

However, in some digital interactions, there is evidence of denying alterity through comments or publications that violate the other. In this regard, a participant allows us to understand through his intervention, in which he narrates part of his personal experience, that there is still resistance to accepting gender diversity and welcoming those who challenge us from the manifestation of their difference:

If someone comes to light, sometimes they attack that person because it is something wrong because God does not say it, then it is like telling the other person that even though they think that way, from the religious point of view, the other person does not. So, I write to them to respect them because each person has their point of view and way of living (source: semi-structured interview in Colombia, 2023).

Another form of violence that occurs in the context of VSNs is cyberbullying. This form of violence may be more difficult to perceive at school than aggression in face-to-face relationships (Marín-López et al., 2020). One participant recounted an experience of cyberbullying perpetrated by an individual affiliated with the educational institution where she was enrolled. “I was the victim of bullying and requested assistance because the individual who initiated the harassment was a member of my social circle. I was advised to seek help from the school by some parties.” (Source: Focus Group in Colombia, 2023).

Regarding the classification of cyberbullying as a violent form of relationship within VSNs, Zych et al. (2018) propose that including the strengthening of socioemotional skills in school programs and educational policies can prevent bullying in VSNs and raise awareness among young people of the importance of caring for the other. Indeed, students express their interest in feeling more accompanied by the school in this aspect “I would like them to promote workshops in schools on the good use of social networks; I would also like them to hold workshops on equality among all and respect for others” (source: focus group in Colombia, 2023); “sometimes they have given talks to raise awareness and that, but others who come to the Institute, teachers do not talk about it” (source: focus group in Spain, 2023).

Accordingly, the ethical encounter with the other represents an invitation to welcome the individual into our lives and to recognize the radical difference between ourselves and the other (Lévinas, 2003). It is important to note that, in addition to the face-to-face context of ethical encounters with others, VSNs are spaces where adolescents form relationships of alterity in particular ways. These relationships are typified by establishing digital proximity, oriented towards responding to the other, caring for them, and welcoming them through utilizing multimodal resources characteristic of digital platforms (Hill, 2011). However, in VSNs, violent forms of relationship are also manifested, which may be an extension of pre-existing conflicts in the face-to-face plane. In such cases, the school can provide formative elements that allow adolescents to build relationships focused on caring for each other (Zych et al., 2018).

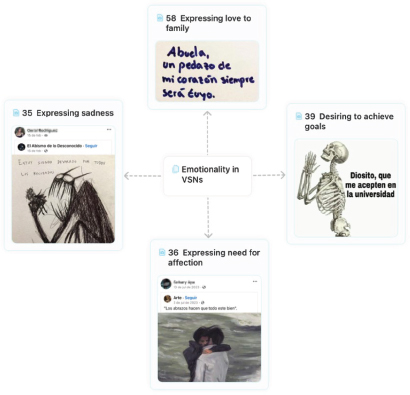

3.2.2. Emotionality in VSNs

VSNs constitute a space of constant performativity for adolescents, who act on these digital platforms using multimodal resources (Scoponi, 2019). In this regard, specific manifestations of emotional performativity emerge due to digital interaction. To illustrate, some participants post memes that represent affect, sadness, the need to feel loved and accompanied, and longings related to their life projects (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Performativity of emotions in VSNs

Caption image above: 58 “Grandmother, a piece of my heart will always be yours”.

Caption right image: 39 “God, may I be admitted to college”.

Caption left image: 35 “I am being consumed by all the memories”.

Caption bottom image: 36 “Hugs make everything feel good”.

Source: Digital field journal

The image can evoke emotional responses in the viewer (Barthes, 1990). Consequently, a photograph, another extensively utilized medium in VSNs, has the potential to evoke a range of emotions in adolescents. To respond to another user’s post and express their affection, adolescents utilize comments accompanied by emojis that represent their emotional state. These resources serve as a means of responding to the alterity that presents a challenge and provokes a reaction in the context of the VSNs scenario (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Forms of response in VSNs

Caption: “Very nice, I love him very much.”

“I love you skinny.”

":D"

“What a great style Bro”.

Source: Digital field journal

The absence of gestures characteristic of face-to-face communication has led to the consolidation of the use of resources such as emojis and GIFs as a frequent practice in virtual social networks (VSNs) to respond to and express emotionality (Marín-López et al., 2020). As Scoponi (2019) observed, emojis have become a prominent feature of communication among adolescents, who employ them to express and perform their emotions. The small reaction icons represent a range of emotions, such as “I like,” “I love,” “I care,” and “I am amused,” as well as more negative emotions like “I am amazed,” “I am saddened,” and “I am angry.” These icons serve as a means of responding to their peers in VSNs.

Although it is accurate to conclude that, in an in-person interaction, the other person invites us to recognize their needs and allow their experiences to affect us (Woo, 2014), it is also possible for us to be moved by the other person’s pain and provide assistance in the context of VSNs. As the participants indicated, when a woman discloses that she has been a victim of mistreatment and presents photographic evidence to substantiate her claim, as one focus group participant in Colombia (2023) observed, “everyone starts to see, to comment that she is not alone in all this.” Similarly, another focus group participant in Spain (2023) noted that “if a man has mistreated a woman, this is made public so that people know about it and so that more people are aware of what is happening.” Another student indicated that witnessing animal abuse evokes a similar emotional response and motivates him to take action. He stated, “If they harm a dog, I will post the images on social media to denounce the abuse.” (Source: Focus group in Spain, 2023).

The distinctive modes of communication and interpersonal dynamics within VSNs facilitate the emergence of alterity, compelling us to attend to it and respond with novel resources (Ure, 2017). Deploying memes, images, reactions, and narratives that evoke emotional responses gradually gives rise to new forms of engagement with the other in VSNs (Scoponi, 2019). Furthermore, the utilization of emojis as a means of responding to the publications of others represents a distinctive method of demonstrating that they have succeeded in evoking a reaction and that we are not apathetic towards that aspect of their lives that they choose to share on the VSNs.

3.2.3. Digital identity as a product of the relationship with others

In the VSNs, adolescents experience the ontological feature of needing alterity to build their identity (Alonso-Sainz, 2021). In terms of the significance of the opinions and perceptions of the other to configure the digital self, one student stated, “You must take care of your image, who you are, and more than anything else, your profile and what you want to make known” (source: focus group in Colombia, 2023). Participants try to build a style that characterizes their identity to their followers in the VSNs: “I would like to be seen as I am, that I like rock, metal, in fact I share many rock and metal songs, I also share photos with my style of clothing in the stories” (source: focus group in Colombia, 2023).

Teenagers create their publications with others in mind, taking care of the details and how they present themselves to their contacts in the VSNs, which is what Sibilia (2008) calls alter directed identity. In this regard, one student refers to the importance of being authentic in her publications so that others can get to know her: “If you look at my profile, you can get a general idea of what I am like and the songs I like” (source: focus group in Spain, 2023). Another student expressed how she seeks to be perceived by her peers in the VSNs: “I like them to see that I make art and that they think I have an artistic way of thinking” (source: semi-structured interview in Colombia, 2023).

In this construction of their digital image, adolescents post photos on their VSNs that reproduce certain practices related to gender stereotypes (Martín-Cárdaba et al., 2024; Serrate-González et al., 2023). These findings align with this research, as a male participant shares photos on his VSNS that represent his affiliation with the urban hip-hop culture, including garments such as the durag and the velvet outfit (Figure 9). In contrast, one participant is interested in creating narratives through photographs that showcase her femininity. She does this by posing in a way that expresses her individuality through her facial expression and makeup to highlight her uniqueness (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Gender stereotypes in VSNs

Source: Digital field journal

In face-to-face contexts and virtual social networking sites (VSNs), the face plays a significant role in shaping our identity (Alonso-Sainz, 2021). Using a profile picture in VSNs facilitates recognition by others, thereby instilling a sense of confidence that enables more active engagement in online interactions. In examining the profile pictures of adolescents, it is evident that they frequently select images captured in front of a mirror, showcasing their mobile phone and, on occasion, only a portion of their face (Figure 10).

Figure 10

The face as part of the digital profile

Source: Digital field journal

Similar to how identity is configured in the face-to-face context, adolescents need relationships with others to build their digital identity (Alonso-Sainz, 2021). As García-Ruiz et al. (2018) expose, the use of images in selfies and profiles is an essential resource for the construction of digital identity. Therefore, the school must provide adolescents with formative elements that contribute to the construction of their identity and be responsible for the part of privacy they decide to share in the VSNs.

Just as it happens in the ethical event of the encounter with the other in face-to-face contexts, adolescents also express their willingness to take care of the other in the VSNs space. On digital platforms, resources such as comments and reactions are used to provide answers to the other who seeks to be heard and recognized. Through the performativity of emotions and the presentation of their digital identity, adolescents create proximity with their peers to strengthen bonds of friendship or even initiate new social ties.

Since adolescents establish relationships with others in parallel in the VSNs and at school, educational policies for digital training and coexistence processes in schools must adopt a categorical approach to fostering relationships of alterity on digital platforms. Similarly, curricular programs must incorporate spaces for reflection on the manifestations of alterity in VSNs, the underlying causes, and potential strategies for addressing the challenges of welcoming the other and responding to the vulnerabilities that can emerge in the digital context.

4. Conclusions

This research aimed to broaden the frameworks of representation of youth at school by analyzing the way in which adolescents construct relationships of alterity in VSNs. The analysis was developed through two main categories: virtual social networks and digital alterity.

The first category made it possible to recognize that VSNs are essential spaces for adolescent interaction since, in these scenarios, they find opportunities for entertainment and strengthening friendship ties. The main motivations for adolescents to use VSNs are the desire to obtain recognition from their peers and to express their personalities freely. In order to relate to others on digital platforms, students use specific socio-emotional skills that allow them to be empathetic and supportive.

In contrast, the second category, digital alterity, facilitated an examination of how adolescents interact with others within the VSNs context. In these digital spaces, adolescents establish relationships of alterity, demonstrating respect for their peers’ differences, a willingness to care for others, and sensitivity to their peers’ suffering. The relationship with the other on these digital platforms is of such significance that adolescents construct their identity to be recognized, accepted, and valued by their contacts.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that social ties during adolescence are currently constructed simultaneously in both face-to-face and digital contexts. Consequently, enhancing our comprehension of the phenomenon of alterity in VSNs is imperative. The research on cyberbullying (e.g., Fernández-Montalvo et al., 2015; Romera et al., 2021; Zych et al., 2018) provides a foundation for developing digital training programs for students. However, the focus of these investigations is on the risks that emerge when interacting with VSNs. It is, therefore, essential to expand our understanding of the nature of relationships with others in the context of alterity. This will provide new conceptual elements for designing educational policies and training programs to promote the ethical use of VSNs.

Similarly, digital alterity has to be a guiding category in the design and implementation of school coexistence programs to provide adolescents with tools to advance in their socioemotional development so that the encounter with the other on digital platforms is characterized by care and respect for their differences.

As limitations of the present study, it is important to mention that, despite the bonds of trust established with the participants through the interactions in the VSNs, the presence of the researcher and, mainly, the influence of algorithms in the forms of relationship and the construction of the adolescents’ identity may hinder the deep understanding of the experiences of alterity (Hine, 2004; Pink et al., 2016). Another limitation lies in the fact that many online interactions are inaccessible, such as those occurring in private chats or closed groups (Pink et al., 2016).

Given the intrinsic relationship between digital experiences and face-to-face interactions (Hine, 2004), future studies would benefit from combining participant observation in both settings to understand adolescents’ experiences of alterity better. Furthermore, future research must examine the ethical implications of interactions with others in emerging virtual reality and metaverse environments.

References

Alonso-Sainz, T. (2021). “Don’t Be Your Selfie”: The Pedagogical Importance of the Otherness in the Construction of Teenagers’ Identity. In Identity in a Hyperconnected Society (pp. 49–60). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85788-2

Andrade-Vargas, L., Iriarte-Solano, M., Rivera-Rogel, D., & Yunga-Godoy, D. (2021). Jóvenes y redes sociales: Entre la democratización del conocimiento y la inequidad digital. Comunicar, 29(69), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.3916/C69-2021-07

Ardèvol, E., Bertrán, M., Callén, B., & Pérez, C. (2003). Etnografía virtualizada: la observación participante y la entrevista semiestructurada en línea. Athenea Digital, 3, 72–92. 72–92. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/537/53700305.pdf

Barthes, R. (1990). La cámara lúcida. Nota sobre la fotografía (1st ed.). Paidós.

Benavides-Lara, M. A., Pompa Mansilla, M., De Agüero Servín, M., Sánchez-Mendiola, M., & Rendón Cazales, V. J. (2022). Los grupos focales como estrategia de investigación en educación: algunas lecciones desde su diseño, puesta en marcha, transcripción y moderación. CPU-e, Revista de Investigación Educativa, 34. https://doi.org/10.25009/cpue.v0i34.2793

Biernesser, C., Sewall, C. J. R., Brent, D., Bear, T., Mair, C., & Trauth, J. (2020). Social media use and deliberate self-harm among youth: A systematized narrative review. Children and Youth Services Review, 116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105054

Bucknell Bossen, C., & Kottasz, R. (2020). Uses and gratifications sought by pre-adolescent and adolescent TikTok consumers. Young Consumers, 21(4), 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-07-2020-1186

Cebollero-Salinas, A., Cano-Escoriaza, J., & Orejudo, S. (2022). Social Networks, Emotions, and Education: Design and Validation of e-COM, a Scale of Socio-Emotional Interaction Competencies among Adolescents. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052566

Demaria, F., Pontillo, M., Di Vincenzo, C., Bellantoni, D., Pretelli, I., & Vicari, S. (2024). Body, image, and digital technology in adolescence and contemporary youth culture. Frontiers in Psychology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1445098

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

Fam, J. Y., Männikkö, N., Juhari, R., & Kääriäinen, M. (2022). Is Parental Mediation Negatively Associated With Problematic Media Use Among Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 55(2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000320

Fernández-Montalvo, J., Peñalva, A., & Irazabal, I. (2015). Internet Use Habits and Risk Behaviours in Preadolescence. Comunicar, 22(44), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.3916/C44-2015-12

Flick, U. (2015). El diseño de investigación cualitativa. Morata.

García-Ruiz, R., Morueta, R. T., & Gómez, Á. H. (2018). Redes sociales y estudiantes: motivos de uso y gratificaciones. Evidencias para el aprendizaje. Aula Abierta, 47(3), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.47.3.2018.291-298

Gil-Quintana, J., & Amoros, M. F. G. (2020). Posts, interactions, truths and lies of Spanish adolescents on Instagram. Texto Livre, 13(1), 20–44. https://doi.org/10.17851/1983-3652.13.1.20-44

Gil-Ruiz, F. J., & Hernández-Herrera, M. (2023). Ron da error: el consumo digital de los jóvenes a la luz de las tesis de Byung-Chul Han. Palabra Clave, 26(3), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2023.26.3.3

Gomez-Baya, D., Rubio-Gonzalez, A., & Gaspar de Matos, M. (2019). Online communication, peer relationships and school victimisation: a one-year longitudinal study during middle adolescence. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 24(2), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2018.1509793

Granados, B. G., Quintana-Orts, C., & Rey, L. (2020). Regulación emocional y uso problemático de las redes sociales en adolescentes: el papel de la sintomatología depresiva. Health and Addictions, 20(1), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.21134/haaj.v20i1.473

Healy, M. (2021). Keeping company: Educating for online friendship. British Educational Research Journal, 47(2), 484–499. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3673

Hill, D. W. (2011). The ethical dimensions of a new media age: a study in contemporary responsibility [University of York]. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/2223/

Hine, C. (2004). Etnografía virtual. UOC.

Hoxhaj, B., Xhani, D., Kapo, S., & Sinaj, E. (2023). The Role of Social Media on Self-Image and Self-Esteem: A Study on Albanian Teenagers. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 13(4), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.36941/jesr-2023-0096

Jaramillo Ocampo, D., Jaramillo Echeverri, L., & Murcia Peña, N. (2018). Acogida y proximidad: Algunos aportes de Emmanuel Levinas a la Educación. Actualidades Investigativas En Educación, 18(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.15517/aie.v18i1.31771

Khatod, S. R. (2024). Empathy education in adolescence may mitigate hate caused by seminal events: a literature review and case presentations by an adolescent. Discover Psychology, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00248-w

Lévinas, E. (1974). Humanismo del otro hombre. In Siglo veintiuno editores.

Lévinas, E. (2001). La huella del otro. Taurus.

Lévinas, E. (2003). Totalidad e infinito. Ensayo sobre la exterioridad (Sexta edición). Ediciones Sígueme.

Machado, E. (2017). Ciberfeminismo: disidencias corporales y género itinerante. REVELL Revista de Estudos Literários Da UEMS, 3(17), 47–75.

Marciano, L., Schulz, P. J., & Camerini, A.-L. (2022). How do depression, duration of internet use and social connection in adolescence influence each other over time? An extension of the RI-CLPM including contextual factors. Computers in Human Behavior, 136, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107390

Marcus, G. (2018). Etnografía Multisituada. Reacciones y potencialidades de un Ethos del método antropológico durante las primeras décadas de 2000. Etnografías Contemporáneas, 4(7), 177–195. https://revistasacademicas.unsam.edu.ar/index.php/etnocontemp/article/view/475

Marín-López, I., Zych, I., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Hunter, S. C., & Llorent, V. J. (2020). Relations among online emotional content use, social and emotional competencies and cyberbullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 108, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104647

Martín-Cárdaba, M. Á., Lafuente-Pérez, P., Durán-Vilches, M., & Solano-Altaba, M. (2024). Estereotipos de género y redes sociales: consumo de contenido generado por influencers entre los preadolescentes y adolescentes. Doxa Comunicacion, 2024(38), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.31921/doxacom.n38a2034

Mateus, J. C., Leon, L., & Núñez-Alberca, A. (2022). Influencers peruanos, ciudadanía mediática y su rol social en el contexto del COVID-19. Comunicacion y Sociedad (Mexico), 19. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2022.8218

Murciano-Hueso, A., Gutiérrez-Pérez, B. M., Martín-Lucas, J., & García, A. H. (2022). Juventud onlife. Estudio sobre el perfil de uso y comportamiento de los jóvenes a través de las pantallas. RELIEVE - Revista Electronica de Investigacion y Evaluacion Educativa, 28(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.30827/RELIEVE.V28I2.26158

Pertegal-Vega, M. Á., Oliva-Delgado, A., & Rodríguez-Meirinhos, A. (2019). Revisión sistemática del panorama de la investigación sobre redes sociales:Taxonomía sobre experiencias de uso. Comunicar, 27(60), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.3916/C60-2019-08

Piccerillo, L., & Digennaro, S. (2024). Adolescent Social Media Use and Emotional Intelligence: A Systematic Review. Adolescent Research Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-024-00245-z

Pink, S., Horst, H., Postill, J., Hjorth, L., Lewis, T., & Tacchi, J. (2016). Digital Ethnography: Principles and Practice. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Popat, A., & Tarrant, C. (2023). Exploring adolescents’ perspectives on social media and mental health and well-being – A qualitative literature review. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 28(1), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045221092884

Portillo Fernández, J. (2016). Planos de realidad, identidad virtual y discurso en las redes sociales. Logos: Revista de Lingüística, Filosofía y Literatura, 26(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.15443/RL2604

Restrepo, E. (2016). Etnografía: alcances, técnicas y éticas (Envión, Ed.; 1st ed.). Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. https://www.ram-wan.net/restrepo/documentos/libro-etnografia.pdf

Reyero, D., Pattier, D., & García-Ramos, D. (2021). Adolescence and Identity in the Twenty-First Century: Social Media as Spaces for Mimesis and Learning. In Identity in a Hyperconnected Society (pp. 75–93). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85788-2

Romera, E. M., Camacho, A., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Falla, D. (2021). Cibercotilleo, ciberagresión, uso problemático de Internet y comunicación con la familia. Comunicar, 67(2), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.3916/C67-2021-05

Sari, D. I., Rejekiningsih, T., & Muchtarom, M. (2020). Students’ digital ethics profile in the era of disruption: An overview from the internet use at risk in Surakarta City, Indonesia. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies, 14(3), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v14i03.12207

Scoponi, P. (2019). Hacia una caracterización del ciberlenguaje adolescente: el caso de la multimodalidad en Facebook. Revista Estudios Del Discurso Digital (REDD), 2, 101–128. https://doi.org/10.24197/redd.2.2019.101-128

Serrate-González, S., Sánchez-Rojo, A., Andrade-Silva, L. E., & Muñoz-Rodríguez, J. M. (2023). Onlife identity: The question of gender and age in teenagers’ online behaviour. Comunicar, 31(75), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.3916/C75-2023-01

Serres, M. (2013). Pulgarcita (M. Serres, Ed.). Fondo de la Cultura Económica.

Sibilia, P. (2008). La intimidad como espectáculo (1st ed.). Fondo de la Cultura Económica.

Statista. (2024). Most popular social networks worldwide as of April 2024, by number of monthly active users. https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

Ure, M. (2017). De la alteridad a la hiperalteridad: la relación con el otro en la Sociedad Red. Sophía, 1(22), 185–204. https://doi.org/10.17163/soph.n22.2017.08

Van Dijck, J. (2016). La cultura de la conectividad: Una historia crítica de las redes sociales. Siglo XXI Editores.

Woo, J. G. (2014). Teaching the unknowable Other: Humanism of the Other by E. Lévinas and pedagogy of responsivity. Asia Pacific Education Review, 15(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-013-9301-x

Zych, I., Beltrán-Catalán, M., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Llorent, V. J. (2018). Social and Emotional Competencies in Adolescents Involved in Different Bullying and Cyberbullying Roles. Revista de Psicodidactica, 23(2), 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicod.2017.12.001