ISSN: 1130-3743 - e-ISSN: 2386-5660

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.31935

PROSPECTIVE TEACHERS AND COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE. A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Futuros docentes y competencia comunicativa. Una revisión sistemática de la literatura

Miguel DE LUCAS*, Daniel CABALLERO JULIA** & Álvaro DIEGO-GONZÁLEZ*

* Universidad CEU San Pablo. Spain.

** Universidad de Salamanca. Spain.

miguel.romeroluis@usp.ceu.es; dcaballero@usal.es; alvaro.diegogonzalez@ceu.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4878-9093; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3758-8314; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8608-7407

Receipt date: 08/04/2024

Acceptance date: 07/11/2024

Online publication date: 01/07/2025

How to cite this article / Cómo citar este artículo: De Lucas, M., Caballero Julia, D. & Diego-González, A. (2025). Prospective teachers and communicative competence. A systematic review of the literature [Futuros docentes y competencia comunicativa. Una revisión sistemática de la literatura]. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 37(2), 1-28, early access. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.31935

ABSTRACT

Purpose: The aim of this article is to carry out a systematic review of the existing scientific literature on the relationship between the Communicative Competence of teachers and prospective teachers in the education sector. Design/methodology: Using the PRISMA 2020 method, high quality scientific databases, detailed later, were searched to finally obtain 53 documents in which the Communicative Competence of teachers and its determinants, effects, strategies and measurement instruments were identified. Results: It was found that the determinants of these competences relate to the personal characteristics of the people doing the communicating and the context in which they find themselves, reporting beneficial effects for students and teachers in educational terms. This demonstrates the importance of training prospective teachers in Communicative Competence. Originality: This study highlights the importance of communicative processes in education. Teacher training is therefore very important. Furthermore, the educational process is valued not as a one-way process for transmitting content, but as a living process, where emotions and feelings are transmitted along with the content.

Keywords: communication; teachers; education; competencies; learning; skills; teaching.

RESUMEN

Propósito: El objetivo de este artículo es realizar una revisión sistemática de la literatura científica existente sobre la relación entre la Competencia Comunicativa de profesores y futuros profesores en el contexto educativo. Diseño/metodología: Aplicando el método PRISMA 2020, se realizó una búsqueda en bases científicas de calidad detalladas posteriormente, para obtener finalmente 53 documentos en los que se identificó la Competencia Comunicativa de los docentes y sus determinantes, efectos, estrategias e instrumentos de medida. Resultados: Se encontró que los determinantes de estas competencias están relacionados con las características personales de quienes se comunican y con el contexto en el que se encuentran, reportando efectos benéficos para alumnos y docentes en términos educativos. De ahí la importancia de formar a los futuros docentes en Competencia Comunicativa. Originalidad: Este estudio pone de manifiesto la importancia de los procesos comunicativos en el contexto educativo. La formación del profesorado en este sentido es muy importante. Además, se valora el proceso educativo no sólo como un proceso unidireccional de transmisión de contenidos, sino como un proceso vivo, donde las emociones y los sentimientos se transmiten junto con los contenidos.

Palabras clave: comunicación; profesores; educación; competencias; aprendizaje; habilidades; enseñanza.

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, the rapid development of science and technology has led to a new pedagogical approach, which emphasises the development of skills rather than the simple transfer of knowledge. This in turn means that teachers’ communicative skills take on significant importance. According to Perrenoud’s (2004) definition, this type of competence should be a basic starting competence that every teacher has.

Thus, Communicative Competence (CC) is understood as the set of skills that allow someone to participate appropriately in specific communicative situations. It refers to a person’s ability to use language effectively and appropriately in different contexts, both orally and in writing, taking into account the linguistic and practical norms of the social and cultural context. This is crucial to develop their personality and enhance their professional training (Halian et al., 2020). Furthermore, communicative skills in teaching are of interest due to their role as a motivational factor, as a basis for decision-making and as a tool to create a good atmosphere in the educational community (Tejada, 2005).

Among the leading competences in teaching, CCs stand out as a key component of professional practice (Vasilyeva et al., 2021). Other authors (Isaeva et al., 2021; Vasilyeva and Nikitina, 2018; Vitello and Greatorex, 2022) argue that certain aspects of interpersonal communicative competence can predict teachers’ leadership behaviour, influencing communicative productivity, professional success, self-realisation, self-determination and socialisation. Good communication with students, parents and other stakeholders in the educational process is considered essential. Furthermore, the development of the teacher’s CCs is vital if students are also to acquire this skill. The literature offers a range of perspectives on what CCs are and what they consist of, which can make it difficult to develop programmes or strategies to improve them. Studying communication as a teaching competence involves mastering a set of skills, such as motivation (Froment et al., 2021), decision-making and the ability to create a good atmosphere in the educational community (Villanueva, 2020). Communication is a necessary basic competence in education (Bravo-Molina, 2023). However, despite extensive evidence on the importance of CC in the teaching-learning process, there are few studies that address this (Gràcia et al., 2020). This becomes more significant if we consider that there are potential factors that could affect these competences, causing them to decrease over time. Such factors include a lack of structured training in these skills, pedagogical deficiencies and organisational limitations, such as a lack of time, conflicting priorities, minimal hierarchical support, the absence of positive incentives to use, train or teach effective communication skills in teaching practice, the need to adapt to new teaching methodologies that integrate ICTs (García-Martínez et al., 2020), cultural and linguistic differences in the classroom (Morales-Acosta et al., 2022), the evolution of educational expectations and the inadequate or insufficient initial training of teachers, which can result in deficiencies in their pedagogical practice over time (Maldonado Alegre et al., 2021).

The above shows the complexity inherent in the development of communicative competence, particularly in the teaching field, as well as the fragmentation of scientific knowledge on this subject. This creates the need to carry out a systematic review of the literature that, first, establishes integrative concepts and theories related to the communicative competences that teachers must possess to enhance the teaching-learning process, and second, determines how to improve the communicative competences of prospective teachers and the instruments that have been used to evaluate them. To achieve these objectives, and assuming a parallel between teaching CC and the effectiveness of the teaching-learning process, two research questions arise:

– What are the determinants and effects of communicative competences in education?

– How can teachers’ communicative competences be improved?

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

The Systematic Literature Review (SLR) is completed following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Page et al., 2021) to carry out the process of searching for and selecting documents. The research was exploratory in nature, and its objective was to explore different theoretical and empirical contributions that can contribute to synthesising knowledge about how teaching communicative competence is linked to pedagogical practice. In addition, the aim was to identify key factors that would allow future empirical applications in the scientific community.

2.1. Registration statement

This SLR has been registered as a General Systematic Review on 22 December 2023, in the field of education.

The registration code is: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/9WK35

Website link: https://archive.org/details/osf-registrations-9wk35-v1

2.2. Information sources and search strategy

To broaden the scope of the search, increase the probability of finding relevant studies and obtain a more representative overview of the existing bibliographic corpus, we consulted the Scopus, Web of Science, DOAJ and ProQuest databases using the Boolean operator “AND” to combine terms and refine the results. In these cases, the search for articles involved the “Title” and “Abstract” fields using the following expressions with their corresponding translations into Spanish: “Future educators AND communication skills”, “Aspiring instructors AND interpersonal abilities”, “Potential educators AND effective communication”, “Future teachers AND communicative proficiencies” and “Prospective educators AND interpersonal competencies”. Under no circumstances were filters used that relate to the quality index of the journal in which they were published. The titles and abstracts of any studies identified as potentially eligible were screened by two independent reviewers, with no discrepancies arising that would require the involvement of a third reviewer.

Additional terms taken from other relevant articles were also included, such as “initial teacher education”, “communication in education”, “communication in the classroom”, “communication and teaching” and “linguistic competence”.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used:

– Publication language: English and Spanish.

– Scientific articles that show the results of theoretical and empirical studies.

– Articles on the factors that determine the communicative competence of teachers and their effects on pedagogical performance, the instruments used to measure and evaluate these competences, and the programmes that have improved the communicative competence of prospective teachers.

– Doctoral theses and conference papers.

– Priority is given to scientific articles less than five years old.

Furthermore, the exclusion criteria were as follows:

– Academic works not subject to peer review.

– On the topic of online education or learning a second language.

– Works with no methodological description.

– Works with conclusions not supported by results.

– Bachelor’s or master’s dissertations, monographs and reports.

During the data extraction process, a form was used in which the relevant information was recorded: author, year of publication, country, study design and main results. Risk of bias in the selected publications was not considered.

2.4. Analysis

The publications selected after this process have been analysed following a dual analysis perspective: one of a qualitative nature, based on a documentary and interpretive analysis, and another of a quantitative nature, based on the Statistical Analysis of Textual Data, otherwise known as text mining. These two perspectives come together to complete the analysis of the literature over three phases: 1) a first reading and initial classification of the documentation, 2) use of text mining and first quantitative analysis; and 3) a final exhaustive analysis of the documents from an interpretive perspective.

For the first phase, the information from each item included in the systematic review was processed in two stages:

− Stage 1: Preliminary reading and simplification of the information derived from the discussion of results and conclusions. During this initial phase, superfluous and redundant texts were eliminated based on interpretive relevance criteria.

− Stage 2: Classification of publications by Unit of Analysis (Ua). At this stage, each publication was assigned to a broad thematic area based on the results of the first reading. In total, we have three Ua’s or main thematic areas created ad hoc:

Ua1, “Determinants and effects of communicative competences”;

Ua2, “Strategies for improving communicative skills”;

Ua3, “Measuring communicative competences”.

The second phase included text mining based on the guidelines established by Caballero-Julia & Campillo (2021). This analysis involved the creation of a textual data matrix from the abstracts. For this purpose, a text document was generated that could be recognised by the IRaMuTeQ computer program. (LERASS, n.d.) with the following structure:

**** * ID_1

(first abstract)

**** *ID_2

(second abstract)

**** *ID_3

(third abstract)

As part of this process, a lemmatization protocol was applied (Lebart et al., 2000). The result is a Xpxn lexical matrix with p words and n items that is recalculated using the characterisation value described by Caballero-Julia & Campillo (2021):

To finish this quantitative phase, a MANOVA Biplot was applied (Gabriel, 1995; Vicente, 1992) which creates a low-dimensional and simultaneous graphical representation of the data set (cases and variables) contained in the matrix Xpxn. The resulting chart looks for the maximum differentiation between groups (Ua’s) in addition to identifying the variables (words) causing that differentiation.

The third and final phase takes all the information from the previous one and seeks to deepen and synthetically reconstruct the set of results found in the process. For this purpose, there was an attempt to categorise information into specific groups, which enables the interpretation around common ideas. The text fragments most aligned with the review objectives were classified and coded according to their respective Ua’s. The categories used were:

– “CC for 21st Century Education”,

– “Teachers’ communication skills”,

– “Determinants of communicative skills”,

– “CC Correlations”, “Effects of CC on students”,

– “Programmes to improve teachers’ communicative skills”,

– “Programmes to improve students’ communicative skills”

– “Measurement of CCs”.

Finally, the information was restructured narratively. In this final phase, after interpreting the information units corresponding to each category, the significance of the findings was presented, contextualizing them and providing empirical evidence of all the records used during the review.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

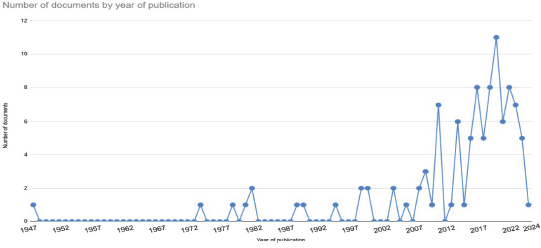

From a basic bibliometric analysis, it can be observed that publications on this topic have been of increasing interest, especially since around 2010 (see Figure 1). Despite this growth in their number, annual publications have not been constant and it is in recent years in particular that we find more scientific articles on the subject.

FIGURE 1

NUMBER OF DOCUMENTS PUBLISHED BY YEAR

Source: Own development

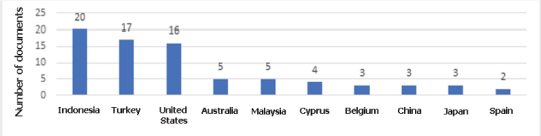

The geographical distribution is not homogeneous either, with a greater concentration in countries such as Indonesia, Turkey and the United States, which are significantly far ahead of the rest (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

NUMBER OF DOCUMENTS PUBLISHED BY COUNTRY

Source: Own development

3.1. Phase 1 – First reading and initial classification of the documents

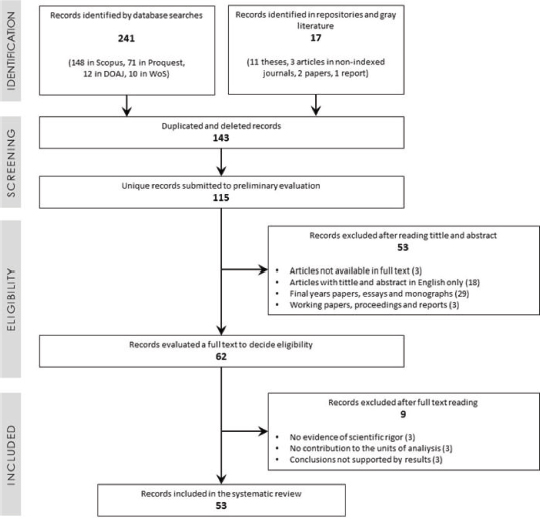

A sample of documents for analysis was obtained from the first reading of the texts, after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria and following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (Page et al.., 2021). It consisted of a total of 53 publications that successfully passed the screening process and whose contributions were considered for the established purposes. Figure 3 shows the flow of the process involved in searching for and selecting the documentary records to be included in the review.

FIGURE 3

FLOW OF THE BIBLIOGRAPHIC SEARCH AND SELECTION PROCESS

Source: Own development

The primary contributions of each study were tabulated according to author, year of publication, title, focus, unit of analysis, and main contribution. Due to the nature of the study’s scope and the purpose of the review, the results obtained were grouped according to the units of analysis to which they referred. Of the 45 publications retained, three main areas could be identified which, as indicated in the methodology of this study, included “Determinants and effects of communicative competences” (Ua1), “Strategies for improving communicative skills” (Ua2) and “Measuring communicative competences” (Ua3). In numerical terms, we have 20 publications belonging to Ua1, 10 to Ua2 and 15 to Ua3. However, some publications, due to their nature, make contributions that could be attributed to several Ua’s.

3.2. Phase 2 – Statistical analysis of textual data from the units of analysis

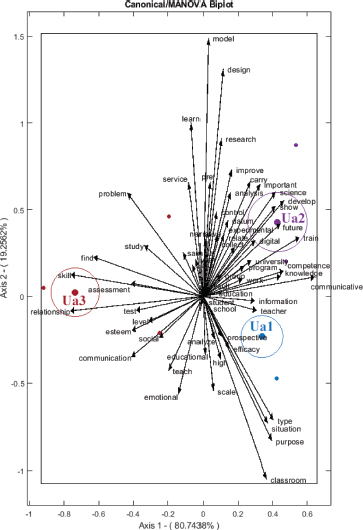

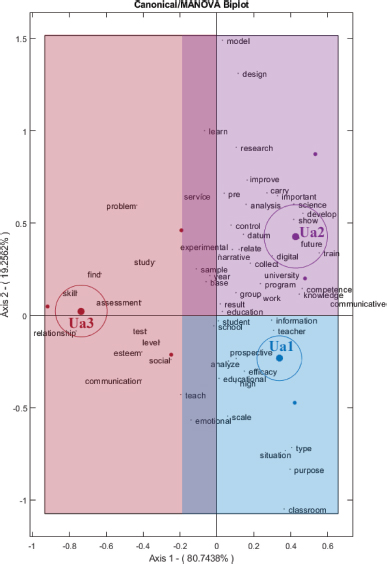

Phase 2 of this study completes, confirms and improves the selection and classification method of Phase 1. The text mining performed using a MANOVA Biplot allows us to distinguish between the different thematic areas in the literature on the basis of the information contained in the abstracts (Figure 4). In this way, we can identify those publications that are (dis)similar to each other in a two-dimensional space containing the contributions to each of the topics covered. At the same time, the MANOVA Biplot in the figure allows us to identify the words that constitute these themes.

FIGURE 4

TEXT MINING USING A MANOVA BIPLOT OF THE UA’S

Source: Own development

Looking at Figure 4, it is quickly apparent that the Ua’s proposed in the first phase are, in fact, clearly differentiated areas since their confidence limits (represented by a circle around the centre of the group) do not intersect at any point.

Similarly, it can be seen that the vectors are arranged in the space pointing to each of the Ua’s. This can again be interpreted as a clear sign of the separate identity of each of the Ua’s. While it is true that Ua1 and Ua2 may have certain similarities in their projection on certain words (those aligned with axis 1), both are clearly differentiated with respect to the second axis.

In a more detailed interpretation of the figure (see Figure 5 in which the vectors have been replaced with points to make it easier to interpret) one can observe the words classroom, purpose, situation, type, educational, efficacy, teach, scale, emotional, prospective and teacher. In other words, the reader is faced with a series of publications that have addressed the purposes and situations in the classroom to evaluate the determinants and effects of communicative competence with a clear emphasis on its effectiveness and the emotional aspects associated with it.

FIGURE 5

THEMATIC AREAS RESULTING FROM THE TEXT MINING USING MANOVA BIPLOT

Source: Own development

In relation to Ua2, one can see a more varied range of words, some of which stand out, such as model, design, learn, research, improve, important, science, develop, future, university and program. As a whole, they seem to indicate a theme concerned with the modelling and implementation of programmes, especially at the university academic level, which allow the development and enhancement of communicative competences. Or, to put it another way, strategies for improving communicative competences. Finally, Ua3 includes a subset of words such as relationship, skill, find, assessment, esteem, test, level, communication, study, problem and social. The Ua therefore aims to measure communicative competences and their relationship with educational, social or esteem elements. In short, the figure showing the results from the MANOVA Biplot offers a thematic map that offers us a global interpretation of the publications on teachers’ communicative competences.

3.3. Phase 3 – Final documentary and interpretative analysis

In this final phase of the review, the aim is to further analyse the set of data collected and to synthetically reconstruct the results found in the process.

3.3.1. Ua1: Determinants and effects of CC

21st Century Education. CC

Communication can be interpreted as the process of generating, transferring and interpreting knowledge. Communicative skills are defined through three dimensions: personal assets for communication, the results to be achieved and the means to achieve them. Among personal assets for communication, communicative skills are the knowledge, abilities or attitudes that a person possesses that allow them to convey knowledge. Among the results of the communication, these skills must guarantee a positive response from the person receiving the information. According to Domingo-Coscollola et al. (2020), effective communicative competences must allow the recipient to successfully understand, internalise and apply the information or instructions received.

The definition of communicative skills includes personal communication assets. These are learned behaviours that allow a person to establish satisfactory relationships, eliciting positive responses from others and facilitating a social life. Communication skills have been understood as the tools used to eliminate barriers to effective communication (MTD Training, 2021; cited by Yildirim, 2021). From a general perspective, the communicative skills are listening, writing and speaking. (Malik et al., 2018). However, in this study we want to examine each of them in more depth. Rubio (2023) goes into more detail on the essential components of teacher communicative competence in the classroom: active listening, clear verbal expression, effective non-verbal communication, empathy, and the ability to adapt teaching strategies to the communicative context.

Teachers’ communicative skills

Teachers constantly obtain, classify, analyse and explain information to students and this can determine the success of the teaching and learning in the classroom (Einsenring & Margana, 2019). Hence, interaction becomes the main means for the teacher and the students to exchange their ideas, feelings, opinions and perceptions, making it evident that education occurs automatically in a communicative process. This is why, nowadays, communicative competence (speaking and listening) forms part of most curricula, from nursery school to university (Grácia et al., 2019). In addition to the above, authors such as Ferri et al. (2019) and Rubio (2023) argue that, in addition to speaking and listening, communicative competences encompass other skills, including the ability to read and write effectively, as well as the ability to adapt communication to different contexts and audiences. Despite Remacle et al. (2023) arguing that verbal communication is the predominant type of communication in education, since teachers, through their voice, attract the attention of the students and manage classroom situations, communicative competences are essential not only for the effective transmission of knowledge, but also to foster an inclusive and participatory learning environment.

Other authors argue that teachers should possess another set of competences, the following being of particular importance:

– Linguistic Competence, which refers to the teacher’s ability to correctly use the language in its different forms (verbal and written), including grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation. According to Sornoza-Briones and Mendoza-Bravo (2023), a teacher with linguistic competence can construct and understand grammatical statements, which is essential for effective communication in the classroom.

– Sociolinguistic Competence, referring to the ability to adapt language to the social and cultural context in which the teacher is working, which is essential in interacting appropriately with students from different cultures and to foster an inclusive environment. Neira-Piñeiro et al. (2018) argue that this competence allows teachers to recognise linguistic and cultural variations that can influence communication.

– Pragmatic Competence, understood by Gràcia et al. (2019) as the ability of teachers to use language effectively in the classroom to facilitate meaningful and relevant interactions in specific situations, taking into account the context and communicative intention.

– Communicative Didactic Competence, through which the teacher’s communication skills are combined with the pedagogical strategies they use. On this particular point, Ferri et al. (2019) argue that teachers must be able to interact with students to facilitate learning, which includes using different teaching strategies and adapting their communication to the needs of the students.

– Digital Competence, which involves the effective use of information and communication technologies (ICT) during pedagogical practice to improve communication and learning (Girón et al., 2019).

– Intercultural Competence, which refers to the ability of teachers to communicate and work with people from different cultures, recognising and respecting the diversity of their cultural beliefs and values, and promoting an intercultural dialogue that encourages the creation of an inclusive learning environment (Miao & Lepeyko, 2023).

– Active Listening Competence, understood as the ability to listen carefully to students to understand their needs and respond appropriately to them, establishing an effective dialogue and encouraging the active participation of students for a meaningful educational experience (Guleç & Leylek, 2018).

– Feedback Competence, which describes the ability demonstrated by the teacher to provide constructive and effective feedback to their students, in such a way that allows students to understand their strengths and areas for improvement, increase their motivation and improve their academic performance (García-Martínez et al., 2020).

Therefore, a teacher with good CCs must:

– Structure the conversation through a sequence of steps aimed at problem solving and mutual understanding (Gartmeier et al., 2015). Include the opening of lines of communication (Ihmeideh et al., 2010).

– Listen carefully to the other persons response before responding (Ihmeideh et al., 2010). Added to this competence is the ability to analyse students’ verbal and non-verbal responses, for example, through thoughts or body reactions (Saka & Surmeli, 2010).

– Avoid being defensive (Ihmeideh et al., 2010).

– Use positive statements instead of accusatory statements (Ihmeideh et al., 2010).

– Use appropriate verbal and non-verbal language (Gartmeier et al., 2015; Saka & Surmeli, 2010).

– Provide effective feedback, instantly assessing its effectiveness (Saka & Surmeli, 2010).

– Establish a climate of mutual respect and trust (Gartmeier et al., 2015).

– Show empathy, understanding other people and help them to be understood (Guleç & Leylek, 2018).

– Transparency: be natural and express their emotions and feelings without hiding them (Guleç & Leylek, 2018).

– Equality: treat students as equals because they are human beings. There should be no psychological difference based on role or status (Guleç & Leylek, 2018).

– Effectiveness: assess whether people are learning. The above includes thoughts or behaviours consistent with what has been taught (Guleç & Leylek, 2018).

Determinants of communicative skills

Communicative competences are developed through the performing of activities related to teaching. In fact, the effective development of communicative competence improves the quality of teaching and learning in schools (Shailja, 2022). To promote these activities in a planned and orderly manner, training programmes are developed in multiple aspects, including socio-psychological training to improve emotional intelligence, self-management in communication, group cohesion and the classroom climate (Voronska, 2021) or the presentation of knowledge (Shea, 1947; Van-Dalen et al., 1999).

Among the determinants of the communicative competence of the sender, it is intuition that stands out (Shedletsky, 2021). In fact, Sipman et al. (2021) found that intuition-based professional development has a positive impact on teachers’ pedagogical tact and classroom outcomes, with meditative and physical practices enhancing this skill. Furthermore, knowledge about interpersonal communication is another key aspect of communicative competences. This factor is related to the amount of training the person receives; so much so that Nedzinskaitė-Mačiūnienė and Merkytė (2019) were able to demonstrate that teachers with improved interpersonal communication skills, such as clarity, credibility and familiarity, are more likely to engage in shared leadership within their teaching communities.

In addition, Remacle et al. (2023) argue that among the determining factors of verbal communication are inadequate or excessive vocal patterns that alter the organs responsible for the voice, demonstrating that physiological characteristics also determine communicative performance.

Among the determinants of the receiver, it has been found that the physical, mental and emotional state influences the way in which CCs are manifested (Remacle et al., 2023). As an example, these authors were able to demonstrate that student behaviour alters the communication conditions in the classroom. One of the determining factors was who they were communicating with (patients and other medical staff). Patients in critical health situations had difficulty communicating, which created a greater challenge for the students. Similarly, medical staff may also have characteristics that hinder communication with students, such as a lack of warmth or a lack of responsiveness. Another determining factor was represented by teachers, who, by fulfilling roles as mediators or promoters of discussions in small groups, generated communication spaces that were rated as less challenging by the students.

Finally, among the determinants of communication, one cannot overlook the environment in which the communication takes place and the rules that govern it. Remacle et al. (2023) also demonstrated that ambient noise from hallways and classrooms disrupted teachers’ verbal communication skills. Trang and Hansen (2021) argue that better interpersonal skills and the expectations that teachers place on their students in relation to communication are associated with less conflict in the classroom, directly influencing the process.

Communicative competence correlations

In addition to the determinants of CC, there are other elements related to these. However, when understanding the research designs of the studies, we found that the correlational approach does not allow us to verify whether a relationship is cause-effect, or whether it is a virtuous circle where the cause also acts as an effect and vice versa. The correlations found in relation to CC were linked to personal characteristics and educational characteristics.

Among the personal characteristics, correlations were found between communicative skills and attitudes, economic capital, social capital and self-efficacy. In this regard, Yuksel Sahin (2008) found relationships between communication skills and each of the following:

– Positive self-image. People with a positive self-image have self-esteem, which has been linked to better psychological health and better social adjustment behaviours. It is also related to a proactive style, self-confidence and assertiveness.

– Self-perception of being popular. Popularity is related to people’s physical attractiveness, interest, warmth and sensitivity, self-confidence, kindness, extroversion and fun-lovingness.

– Self-perceived assertiveness. This is related to interpersonal effectiveness and is different to shyness and aggressiveness.

– Financial income. This has been linked to assertiveness, self-confidence and lower levels of submissive behaviours.

– Perception of parents having a democratic style. Interactions with parents are our first social experience. People with democratic-style parents tend to be independent, friendly, expressive, cooperative, aware of other people’s needs, emotionally stable, and have self-confidence and self-esteem.

Studies conducted by Yildrim (2021) and Sumartini et al. (2021) revealed a correlation between the communicative skills of teachers (and future teachers) and the perception of self-efficacy. Belief in self-efficacy influences the learning environment, and the learning environment influences student success. As for training characteristics, we found a correlation between communicative skills and qualifications and the training stage. In this sense, studies by Ihmeideh et al. (2010) and Schurr et al. (1989) showed that prospective teachers with better qualifications have more positive attitudes towards communication than students with lower qualifications. Furthermore, future teachers who are more advanced in their professional careers have a more positive attitude towards communicative skills than students at an average stage and those who are just starting their careers. The above is in keeping with the study by Ulutas and Aksoy (2010), who showed that older students had more self-confidence and better CCs than newer students. Similarly, it has been argued that there is a close relationship between greater self-confidence and conversational skills (Aulia & Apoko, 2022). This is possible because new students enter a different environment to which they must gradually adapt and students learn about communication in the courses, so as they acquire more knowledge, they also acquire more skills.

Effects of CC on students

The effects of communicative skills on students are related to learning and personal development. An example of this is provided by Kordonets et al. (2021) who showed that children with special educational needs are less developed in relation to communicative competence, which hinders their mental and social development.

In addition, for adolescents, communicative competences are crucial for creating effective interactions with other adolescents and with adults, such as teachers, and help students develop leadership skills and increase their self-confidence, as suggested by Demirdag (2022) on demonstrating that effective communication skills mediate the relationship between leadership styles and 21st century skills in teachers.

3.3.2. Ua2: Strategies for improving communicative skills

Despite the importance of communicative skills in education, the study by Gallego-Ortega & Rodriguez-Fuentes (2015) showed that teachers in teacher training programmes for future educators in Spain perceive that students receive little training in this area. However, the number of strategies found to improve teachers’ CC was significant, being aimed at two specific contexts: general and scientific areas. The findings on the strategies and resources used for the aforementioned purpose designed for teachers/future teachers, doctors and students are described below.

Programmes to improve teachers’ communicative skills

The programmes to improve the communicative skills of teachers in general were aimed at strengthening multiple cross-cutting aspects of teaching, such as verbal and non-verbal communication, empathy, collaborative work, dialogue and the voice, among others. In this regard, Kachak & Blyznyuk (2023) argue that the effective development of communicative competence in future teachers involves the use of effective methods and techniques to build knowledge of linguistic norms, rhetorical culture, speech and communication skills in various situations. Regarding strategies aimed at teachers in scientific areas, the following studies were found.

In Spain, special emphasis has been placed on enhancing students’ language skills, covering both native languages and those acquired later in the school environment. This initiative has involved various programmes, one of the most notable being the so-called School Language Project (SLP) (Fabregat Barrios, 2022). According to the authors, the SLP programme is promising, but specific improvement measures in both external and internal aspects are needed to effectively improve students’ communicative competence.

Spektor-Levy et al. (2008) reported on a programme for the development of scientific communication competences. For each of these competences and its components, the authors proposed a series of activities that teachers could implement, such as finding journals related to the discipline, and scanning scientific documents quickly, among others. The authors studied how teachers used the programme over two years and its results. The data showed that teachers who used the methodology adapted the programme to their needs and improved their perception of their communication skills.

Malik et al. (2018) described a programme to improve the scientific communication skills of future physics teachers through a higher-order thinking laboratory. This laboratory incorporates communication skills through (i) understanding the challenges of the laboratory, (ii) producing ideas, (iii) preparing laboratory ideas, (iv) carrying out the activities, and (v) communicating and evaluating the results. Students must complete these activities cooperatively with the help of the teacher. The research showed that the laboratory generated better scientific communication competences in the students who participated, compared to students in a control group who did not participate in the laboratory. The skills acquired were notable in scientific writing, information representation and knowledge presentation.

Yanti et al. (2019) developed a learning model to improve the scientific communication and research skills of future physics teachers through project-based learning. The model consists of five phases: (i) group formation and search for problems, (ii) research design, (iii) research implementation, (iv) analysis of project data, and (v) evaluation and communication of results. Students were asked to work cooperatively with other students and teachers to carry out the project.

For their part, Arsih et al. (2021) implemented a learning model, known as RANDAI, to improve the scientific communication skills of future biology teachers. The method was compared with the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) and Direct Learning methodologies. The three methods have some methodological differences, including the following. The RANDAI method consists of five steps: (i) recite, (ii) analyse the problem, (iii) narrate the solution (discuss to design a research plan), (iv) evaluate the solution (present and reflect on the results of the research) and (v) implement. PBL consists of four activities: (i) presentation of the problem, (ii) resolution of the problem, (iii) communication of the results and (iv) carrying out evaluations. In terms of direct learning, students reviewed material presented by other students and teachers and held a discussion with question and answer sessions. The research showed that the RANDAI method performed better than direct learning in terms of strengthening CC, and the RANDAI method performed better than PBL.

Teachers can recommend a set of actions for students to improve their reading, writing, and critical listening, among other skills such as promoting active listening at home; generating learning experiences that cannot happen at home, such as field trips; encouraging students to be questioning; promoting reading at home; evaluating the news they see on television; promoting teaching or tutoring of other students; and note-taking, among others. In this regard, group reading of different books and teacher support can improve children’s communicative development, promoting efficient participation and fostering a diverse communicative repertoire (Tacilla Cardenas et al., 2020).

3.3.3. Ua3: Measurement of CC

There are different instruments to measure and study the scales for the evaluation of communicative skills. Among these, the so-called (Evaluation of Communication Skills Scale) developed by Korkut stands out (Ahmetoglu and Acar, 2016; Aslan et al., 2018; Balat et al., 2019; Ulutas and Aksoy, 2010). The instrument, with 25 statements measured using a five-point Likert scale, aims to understand a person’s attitudes in their communicative interactions.

The Teacher Communication Skills Scale developed by Çetinkanat (Mentiş Taş, 2018; Tuluham & Yang, 2018; Yeşil, 2010) contains 44 statements with a six-point Likert scale on the dimensions of empathy, transparency, equality, effectiveness and efficiency.

The Communication Skills Inventory instrument, developed by Ersanli and Balci (Tuktun, 2015; Ulutas and Aksoy, 2010), consists of 45 questions with a five-point Likert scale on the cognitive, emotional and behavioural dimensions of communicative skills.

The Communication Functions Questionnaire developed by Burleson and Samter (Aylor, 2003) consists of 31 statements with a five-point Likert scale on eight CC elements: regulation, narrative, referencing, persuasion, reaffirmation, ego support and conflict management.

The Kalamazoo Consensus Statement (Maureen, 2007; Rider et al., 2006), involves different adaptations of the online questionnaire with different numbers of statements, but all to be answered with a five-point Likert Scale on the following dimensions of the communicative competences required in medicine: establishing rapport, starting conversations, requesting information, understanding the perspective of the patient or the patient’s family, sharing information, reaching agreement, sharing accurate information, demonstrating empathy and ending the conversation.

The Effective Communication Skills Scale is an instrument consisting of 34 statements that must be answered using a five-point Likert scale on five dimensions of communicative competences: ego supportive language, active-participative listening, self-recognition, empathy and I-language.

The Communication Skills Test (Fadli & Irwanto, 2020) consists of 43 statements measured using a five-point Likert Scale in the dimensions: verbal, written and social communication. Verbal communication included the verbal presentation of ideas, understanding what is being heard, feedback and presentation. In written communication, they included the written presentation of ideas and written feedback. Social communication included negotiating agreements, communicating with people from other cultures, communicating in different languages and humble communication.

The Communication Skills Evaluation Scale was developed by Karagoz and Kosterelioglu and cited by Yildirim (2021). This instrument was specifically designed to measure teachers’ communicative skills using 25 statements and six dimensions: respect, expressiveness, courage, obstacles, motivation and democratic approach.

Arsih et al. (2021) mention another instrument: the Communication Skills Assessment Rubric developed by Greenstein (2012), an instrument created specifically to measure scientific CC. It consists of seven statements that cover three dimensions: organisation, content and delivery.

Finally, Chang et al.(2022) designed a questionnaire to measure teachers’ communicative competences through students’ perceptions. The instrument consists of 43 questions on the following dimensions: consonants, phonetics, fluency, language, non-verbal communication, listening, adoption of roles, self-presentation, performance towards goals, and understanding other people. Only this instrument provided extensive information on the dimensions assessed in teachers; however, we did not have access to the specific elements of the instrument. In addition, we found that the instruments use Likert scales to assess the different dimensions of CC, which could be useful for developing or adopting an instrument to measure such skills in a specific context.

4. CONCLUSIONS

In relation to Ua1, it can be concluded that CCs depend on the context of the communication (sender, receiver, message, medium, purpose and environment, among others), and can be explained by a fundamental competence: the ability to adapt the communicative style to the communicative context. In this regard, the literature highlights that communicative competence is not limited to the correct use of grammar, but also encompasses the ability to construct messages that are socially appropriate for the specific context in which they are communicated. The teacher’s CCs are closely linked to many of their interpersonal skills that allow interactions with the student to be performed properly, as occurs with the teaching-learning process. From the literature reviewed, it can be inferred that CCs depend on the physical, mental and emotional characteristics of the people who are sending and receiving the messages, as well as the characteristics of the context in which the communication takes place, including the rules, expectations and quality of the communication medium. The literature shows significant correlations between CC and personal attitudinal, cognitive, social and economic characteristics, and it should be noted that it has been impossible to determine whether the covariances are cause-effect relationships or virtuous circles. From another perspective, the results support the idea that well-developed communicative competences not only improve the quality of teaching and learning, but also promote leadership and reduce conflict in the classroom, being positively correlated with teachers’ perceptions of self-efficacy, which directly influences student success. The above highlights the complexity implicit in communication, as well as its effects on the quality of the teaching function and on student learning.

Regarding Ua2, it can be concluded that, firstly, what stands out is the importance of comprehensive programmes to improve the communicative skills of teachers, in both general and scientific areas. These cover aspects such as verbal and non-verbal communication, empathy, working as a team, dialogue, trust, awareness of language skills, and tolerance for errors. Secondly, various strategies aimed specifically at improving communicative skills are mentioned in the literature, including programmes such as the higher order thinking laboratory for future physics teachers, which incorporates communication skills through practical and cooperative activities. The RANDAI model for future biology teachers is also described. This was shown to be more effective than other methods, such as Problem-Based Learning (PBL), in strengthening communication skills. Finally, the need to implement strategies that go beyond the classroom environment and involve the family and the community can be highlighted. In this regard, the importance of training parents in language and communication intervention techniques is mentioned since this is associated with better results for children. In addition, specific initiatives are suggested that teachers can recommend to improve reading, writing and critical listening skills, such as promoting active listening at home, generating learning experiences outside the classroom, encouraging questioning and reading at home, as well as promoting peer-to-peer teaching.

In relation to Ua3, we see that the literature provides a comprehensive view of the different ways of measuring teachers’ communicative competences, presenting a range of instruments going from general scales for evaluating communicative skills to tools specifically designed for the educational and scientific context. These instruments, which generally use Likert scales, evaluate multiple dimensions of communication, including aspects such as empathy, transparency, ability to express oneself and scientific communication skills. In this regard, what stands out is an innovative approach that uses students’ perceptions when evaluating teachers’ communicative competences, thus offering a more comprehensive and student-centred perspective. Consequently, when taken together, the different measurement tools provide a solid foundation for the evaluation and development of communicative skills in education, while allowing these to be adapted to reflect the specific needs of each context.

5. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

Despite the results, the study has some limitations. Firstly, the small number of documents directly related to prospective teachers should be taken into account in further studies. Although the importance of CC in teaching and learning processes has been demonstrated, there is a quantitative shortage of studies, mainly because it is a field that has not yet aroused sufficient interest and is considered relatively new.

A second limitation highlighted by the review is the lack of consensus on what the CC of teachers or future teachers should be. Those seeking to improve their communicative skills must consider factors such as the people with whom they wish to communicate, the medium, the form (verbal or non-verbal), and the discipline (health, physical, legal, etc.), among other aspects. Furthermore, it was found that the physical, emotional and cognitive state of the individuals, along with the amount of training and the environmental conditions, influence the acquisition of CC. Therefore, these aspects must be considered when establishing CC training programmes.

Finally, regarding measurement, although some instruments are available, adapting them to certain studies can be difficult. Therefore, if the aim is to have an empirical study of the CC of future teachers, it would be necessary to consider creating a new instrument for this purpose.

REFERENCES

Ahmetoglu, E., & Acar, I. H. (2016). The correlates of Turkish Preschool Preservice Teachers’ social competence, empathy and communication skills. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 16(2), 188-197. https://doi.org/10.13187/ejced.2016.16.188

Arsih, F., Zubaidah, S., Suwono, H., & Gofur, A. (2021, marzo). The implementation of RANDAI to improve pre-service biology teachers’ communication skills. AIP Conference Proceedings 2330. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0043166

Aslan, H., Kumcağız, H., & Alakuş, K. (2018). An investigation of the relationship between the altruism levels, communication skills and problem solving skills of the elementary education and secondary education teachers. Pegem Egitim ve Ogretim Dergisi, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.14527/pegegog.2018.028

Aulia, N. A. N., & Apoko, T. W. (2022). Self-Confidence and Speaking Skills for Lower Secondary School Students: A Correlation Study. Journal of Languages and Language Teaching, 10(4), 551. https://doi.org/10.33394/jollt.v10i4.5641

Aylor, B. (2003). The impact of sex, gender, and cognitive complexity on the perceived importance of teacher communication skills. Communication Studies, 54(4), 496-509. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510970309363306

Balat, G., Sezer, T., Bayındır, D., & Yılmaz, E. (2019). Self-esteem, hopelessness and communication skills in preschool teacher candidates: A mediation analysis. Cypriot Journal of Educational Science, 14(2), 278-293. https://doi.org/10.18844/cjes.v14i2.3714

Bravo-Molina, A. (2023). La Comunicación como Herramienta Fundamental en la interacción docente-Familia: análisis documental de avances y perspectiva en Colombia. Código Científico Revista de Investigación, 4(E2), 255-278. https://doi.org/10.55813/gaea/ccri/v4/nE2/208

Caballero-Julia, D., & Campillo, P. (2021). Epistemological considerations of text mining: Implications for systematic literature review. Mathematics, 9(16). https://doi.org/10.3390/math9161865

Camus Ferri, M. del M., Iglesias Martínez, M. J., & Lozano Cabezas, I. (2019). Un estudio cualitativo sobre la competencia didáctica comunicativa de los docentes en formación. Enseñanza & Teaching: Revista Interuniversitaria de Didáctica, 37(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.14201/et201937183101

Chang, H. J., Shin, M. S., & Kim, H. J. (2022). A study about recognition of middle school and high school students on teacher’s communication skills. Clinical Archives of Communication Disorders, 7(3), 131-136. https://doi.org/10.21849/cacd.2022.00794

Demirdag, S. (2022). The mediating role of communication skills in the relationship between leadership style and 21st-century skills. South African Journal of Education, 42(2), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v42n2a2053

Domingo-Coscollola, M., Bosco-Paniagua, A., Carrasco-Segovia, S., & Sánchez-Valero, J.-A. (2019). Fomentando la competencia digital docente en la universidad: Percepción de estudiantes y docentes. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 38(1), 167-182. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.340551

Eisenring, M. A. A., & Margana, M. (2019). The importance of teacher-students interacion in communicative language teaching (CLT). PRASASTI: Journal of Linguistics, 4(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.20961/prasasti.v4i1.17052

Fabregat Barrios, S. (2022). Proyecto lingüístico de centro. Cómo abordar la mejora de las habilidades comunicativas desde la institución escolar. Grao. https://doi.org/10.25267/Tavira.2022.i28.1301

Fadli, A., & Irwanto, I. (2020). The Effect of Local Wisdom-Based ELSII Learning Model on the Problem Solving and Communication Skills of Pre-Service Islamic Teachers. International Journal of Instruction, 13(1), 731-746. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2020.13147a

Froment, F., Bohórquez, M. R., & García González, A. J. (2021). El impacto de la credibilidad docente y la motivación del estudiante en la evaluación de la docencia. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 79(280). https://doi.org/10.22550/REP79-3-2021-03

Gabriel, K. R. (1995). MANOVA Biplots for twoway contingency tables. En W. Krzanowski (Ed.), Recent Advances in Descriptive Multivariate Analysis (pp. 227-268). Clarendon Press.

Gallego-Ortega, J. L., & Rodríguez-Fuentes, A. (2015). Communication skills training in trainee primary school teachers in Spain. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 17(1), 86-98. https://doi.org/10.1515/jtes-2015-0007

García-Martínez, I., Sierra-Arizmendiarrieta, B., Quijano-López, R., & Pérez-Ferra, M. (2020). La competencia comunicativa en estudiantes de los grados de Maestro: Una revisión sistemática. PUBLICACIONES, 50(3), 19-36. https://doi.org/10.30827/publicaciones.v50i3.15744

Gartmeier, M., Bauer, J., Fischer, M. R., Hoppe-Seyler, T., Karsten, G., Kiessling, C., Möller, G. E., Wiesbeck, A., & Prenzel, M. (2015). Fostering professional communication skills of future physicians and teachers: Effects of e-learning with video cases and role-play. Instructional Science, 43(4), 443-462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-014-9341-6

Girón Escudero, V., Cózar Gutiérrez, R., & González-Calero Somoza, J. A. (2019). Análisis de la autopercepción sobre el nivel de competencia digital docente en la formación inicial de maestros/as. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 22(3), 193-218. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.373421

Gràcia, M., Jarque, M.-J., Astals, M., & Rouaz, K. (2020). Desarrollo y evaluación de la competencia comunicativa en la formación inicial de maestros. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior, 11(30). https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.20072872e.2020.30.591

Gràcia, M., Jarque, M. J., Astals Murià, M., & Rouaz, K. (2019). La competencia comunicativa y lingüística en la formación inicial de maestros: un estudio piloto. Multidisciplinary Journal of School Education, 8(2 (16)). https://doi.org/10.35765/mjse.2019.0816.06

Greenstein, L. (2012). Assessing 21st Century Skills: A Guide to Evaluating Mastery and Authentic Learning. Corwin: Sage.

Güleç, S., & Leylek, B. S. (2018). Communication Skills of Classroom Teachers According to Various Variables. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(5), 857-862. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1177819

Halian, I., Halian, O., Gusak, L., Bokshan, H., & Popovych, I. (2020). Communicative Competence in Training Future Language and Literature Teachers. Revista Amazonia Investiga, 9(29), 530-541. https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2020.29.05.58

Ihmeideh, F. M., Al-Omari, A. A., & Al-Dababneh, K. A. (2010). Attitudes toward Communication Skills among Students’-Teachers’ in Jordanian Public Universities. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 35(4), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2010v35n4.1

Isaeva, E. L., Dagaeva, R. M., & M.G.Saydullaeva. 2021). Competence-Based Approach As The Basis Of Modern Education. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.05.94

Kachak, T., & Blyznyuk, T. (2023). Development of Communicative Competence of Future Special Education Teachers. Journal of Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University, 10(1), 87-98. https://doi.org/10.15330/jpnu.10.1.87-98

Kordonets, V., Nazarenko, M., Papka, S., & Maliy, P. (2021). Psychological and pedagogical peculiarities of the development of communicative comptence of children with special educational needs. Scientific papers of Berdiansk State Pedagogical University Series Pedagogical sciences, 1(2), 75-81. https://doi.org/10.31494/2412-9208-2021-1-2-75-81

Lebart, L., Salem, A., & Bécue, M. (2000). Analisis Estadistico de Textos. Milenio.

LERASS. (n.d.). IRaMuTeQ (0.7 alpha 2). http://www.iramuteq.org/

Maldonado Alegre, F. C., Solís Trujillo, B. P., Brenis García, A. J., & Cupe Cabezas, W. V. (2021). La ética profesional del docente universitario en el proceso de enseñanza y aprendiza. REHUSO Revista de Ciencias Humanísticas y Sociales, 6(3), 136-148.

Malik, A., Setiawan, A., Suhandi, A., Permanasari, A., Dirgantara, Y., Yuniarti, H., Sapriadil, S., & Hermita, N. (2018). Enhancing communication skills of pre-service physics teacher through hot lab related to electric circuit. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 953(1), 12017. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/953/1/012017

Maureen, E. K. (2007). A Practical Guide for Teachers of Communication Skills: A Summary of Current Approaches to Teaching and Assessing Communication Skills. Education for Primary Care, 18(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2007.11493520

Mentiş Taş, A. (2018). Examination of the Relationship between the Democratic Attitude of Prospective Teachers and Their Communication Skills. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(5), 1060-1068. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2018.060527

Miao, J., & Lepeyko, T. (2023). Developing college teachers’ intercultural sensitivity in a multicultural environment (Desarrollo de la sensibilidad intercultural de los docentes universitarios en entornos multiculturales). Culture and Education, 35(2), 450-473. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2023.2177008

Morales-Acosta, G., Mardones Nichi, T., de Aquino Albres, N., Muñoz Vilugrón, K., & Rodríguez Montano, I. (2022). Competencia comunicativa intercultural en las voces docentes en un contexto escolar con diversidad sorda de la región metropolitana, Chile. Diálogo andino, 67, 227-239. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0719-26812022000100227

MTD Training. 2021). Effective Communication Skill. https://www.mtdtraining.com/

Nedzinskaitė-Mačiūnienė, R., & Merkytė, S. (2019). Shared Leadership of Teachers through their Interpersonal Communication Competence. Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia, 42, 85-95. https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.42.6

Neira-Piñeiro, M. del R., Sierra-Arizmendiarrieta, B., & Pérez-Ferra, M. (2017). La competencia comunicativa en el grado de maestro de infantil y primaria. Una propuesta de criterios de desempeño como instrumento para su análisis y evaluación. Revista Complutense de Educación, 29(3), 881-898. https://doi.org/10.5209/RCED.54145

Page, M., Boutron, I., Shamseer, L., Brennan, S., Grimshaw, J., Li, T., McDonald, S., Thomas, J., & Whiting, P. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(71). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Perrenoud, P. (2004). Desarrollar la práctica reflexiva en el oficio de enseñar. Graó.

Remacle, A., Bouchard, S., & Morsomme, D. (2023). Can teaching simulations in a virtual classroom help trainee teachers to develop oral communication skills and self-efficacy? A randomized controlled trial. Computers and Education, 200, 104808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104808

Rider, E. A., Hinrichs, M. M., & Lown, B. A. (2006). A model for communication skills assessment across the undergraduate curriculum. Medical teacher, 28(5), 127-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590600726540

Rubio Gonzalez, G. G. (2023). Competencias comunicativas docentes en el aula mediante el uso de estrategias de enseñanza. DIALÉCTICA, 1(21). https://doi.org/10.56219/dialctica.v1i21.2326

Saka, M., & Surmeli, H. (2010). Examination of relationship between preservice science teachers’ sense of efficacy and communication skills. Procedia-Socialand Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 4722-4727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.757

Schurr, K. T., Ruble, V. E., Henriksen, L. W., & Alcorn, B. K. (1989). Relationships of national teacher examination communication skills and general knowledge scores with high school and college grades, Myers-Briggs type indicator characteristics, and self-reported skill ratings and academic problems. Educational and psychological measurement, 49(1), 243-252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164489491027

Shailja, P. (2022). Interactive Teaching Model - An Effective Way to Cultivate Students’ Communicative Competence. Journal of Theory and Practice of Contemporary Education, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.53469/jtpce.2022.02(01).02

Shea, M. E. (1947). Education of the elementary school teacher in communication skills. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 33(2), 222-224. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335634709381296

Shedletsky, L. (2021). What Does Social Intuition Theory Have to Do With Communicating? (pp. 18-48). https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7439-3.ch002

Sipman, G., Martens, R., Thölke, J., & McKenney, S. (2021). Professional development focused on intuition can enhance teacher pedagogical tact. Teaching and Teacher Education, 106, 103442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103442

Sornoza-Briones, C. M., & Mendoza-Bravo, K. L. (2023). Estrategia didáctica para desarrollar competencias lingüísticas desde la comprensión lectora en el Subnivel Medio. MQRInvestigar, 7(4), 1685-1705. https://doi.org/10.56048/MQR20225.7.4.2023.1685-1705

Spektor-Levy, O., Eylon, B. S., & Scherz, Z. 2008). Teaching communication skills in science: Tracing teacher change. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(2), 462-477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.10.009

Sumartini, T. S., I.Maryati, & Sritresna, T. (2021). Correlation of self-efficacy on mathematical communication skills for prospective primary school teachers. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1987(1), 12037. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1987/1/012037

Tacilla Cardenas, I., Vásquez Villanueva, S., Verde Avalos, E. E., & Colque Díaz, E. (2020). Rendimiento académico: universo muy complejo para el quehacer pedagógico. Revista Muro de la Investigación, 5(2), 53-65. https://doi.org/10.17162/rmi.v5i2.1325

Tejada, J. (2005). El trabajo por competencias en el prácticum: cómo organizarlo y cómo evaluarlo. Revista electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 7(2). http://redie.uabc.mx/vo7no2/contenido-tejada.html

Trang, K. T., & Hansen, D. M. (2021). The Roles of Teacher Expectations and School Composition on Teacher–Child Relationship Quality. Journal of Teacher Education, 72(2), 152-167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487120902404

Tuktun, O. F. (2015). Prospective teacher’s communication skills level: Intellectual, emotional and behavioral elementary. The Anthropologist, 19(3), 665-672. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2015.11891701

Tuluham, S. M., & Yalcinkaya, M. (2018). The Effect of Communication Skills Training Program on Teachers’ Communication Skills, Emotional Intelligence and Loneliness Levels-ProQuest. Journal of Cercetare si Interventie sociala, 62, 151-172. https://www.proquest.com/openview/fe69f70a1b7699e7f1c38f9ce09b1e82/1?pq-origsite=gscholarandcbl=2031098

Ulutas, I., & Aksoy, A. B. (2010). Communication Skills and Self-esteem elementa Preschool Teacher Trainees. International Journal of Learning, 17(6), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v17i06/47049

Van-Dalen, J., Van-Hout, J. C. H. M., amd A.J.J.A. Scherpbier, H. A. P. W., & Vleuten, C. P. M. Van Der. (1999). Factors influencing the effectiveness of communication skills training: programme contents outweigh teachers’ skills. Medical Teacher, 21(3), 308-310. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421599979590

Vasilyeva, V., & Nikitina, E. (2018). Case of Teachers’ Communicative Competence Development Within the System of Methodological Work in the Context of Preschool Educational Establishments. International Journal of Engineering and Technology(UAE), 7, 619-627. https://doi.org/10.14419/ijet.v7i4.38.24634

Vasilyeva, V., Nikitina, E., Reznikova, E. V, Druzhinina, L. A., & Osipova, L. B. (2021). Structure Of Communication Competence Of Teachers Of Preschool Educational Institutions. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences 2021, Humanity in the Era of Uncertainty. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.12.02.13

Vicente, J. L. (1992). Una alternativa a las técnicas factoriales clásicas basada en una generalización de los métodos Biplot. Universidad de Salamanca.

Villanueva, R. K. (2020). Clima de aula en secundaria: Un análisis entre las interacciones de estudiantes y docentes. Revista Peruana de Investigación Educativa, 12(12), 187-216. https://doi.org/10.34236/rpie.v12i12.178

Vitello, S., & Greatorex, J. (2022). What is competence? A shared interpretation of competence to support teaching, learning and assessment. http://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/insights/What-is-competence-A-shared-interpretation-of-competence-to-support-teaching-learning-and-assessment

Voronska, N. (2021). The use of socio-psychological training for the development of the communicative competence of adolescents in inclusive classes. Psychological journal, 7(6), 39-48. https://doi.org/10.31108/1.2021.7.6.4

Yanti, F. A., Kuswanto, H., & Mundilarto, H. (2019). Development of Cooperative Research Project Based Learning Models to Improve Research and Communication Skills for Prospective Physics Teachers in Indonesia. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology (IJEAT), 8(I. 5C), 740-746. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijeat.E1105.0585C19

Yeşil, H. (2010). The relationship between candidate teachers’ communication skills and their attitudes towards teaching profession. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 919-922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.259

Yildirim, I. (2021). A study on the effect of instructors’ communication skills on the professional attitudes and self-efficacy of student teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 47(4), 605-620. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2021.1902237

Yuksel-Sahin, F. (2008). Communication skill levels in Turkish prospective teachers. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 36(9), 1283-1294. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2008.36.9.1283