ISSN: 1130-3743 - e-ISSN: 2386-5660

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.31881

WILD PEDAGOGIES: NEW CONCEPTIONS FOR RELATIONAL ONTOLOGY IN EDUCATION

Pedagogías salvajes: nuevas concepciones para una ontología relacional en educación

Judit ALONSO DEL CASAR

University of Salamanca. Spain.

judit_alonso@usal.es

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-0485-3196

Date received: 21/02/2024

Date accepted: 17/07/2024

Online publication date: 01/01/2025

How to cite this article / Cómo citar este artículo: Alonso del Casar, J. (2025). Wild Pedagogies: New Conceptions for Relational Ontology in Education [Pedagogías salvajes: nuevas concepciones para una ontología relacional en educación]. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 37(1), 45-63. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.31881

ABSTRACT

At first glance, the concept of “Wild Pedagogies” seems to be an oxymoron. Perhaps because in pedagogy we have inherited a certain preference for the cultivated, the planned, the civilised and the domesticated, it is not surprising that our perceptions conflict with the untamed or even the spontaneous, some of the attributes used to define the “wild” as a simile of what is also lacking in education. However, by narrowing down a total of six databases (Education Research Information Center (ERIC), Dialnet, Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), Scielo and ProQuest), links between pedagogy and wilderness were found to have recently been updated in Environmental Education through the concept of “Wild Pedagogies”. A form that emerges among the Social Science literature in English and that seeks to give prominence to other more-than-human voices in order to break with the stereotypes promoted by Western cultures and the status quo regarding the instrumentalisation of nature in times of predominantly anthropocentric paradigms. In doing so, its relational foundations prioritise less human-centred approaches and claim to give way to new ontologies in education. This paper is situated within the educational-environmental context that gives shelter and theoretical significance to the original term, as well as being a proposal for reflection for Theory of education as a bibliographical analysis that converges with the niche of reflections extracted from what were its six cornerstones until 2022: (#1) Co-Teaching; (#2) Complexity, the Unknown and Spontaneity; (#3) Locating the Wild; (#4) Time and Practice; (#5) Socio-Cultural Change; (#6) Building Partnerships and Human Community; and until 2024: (#7) Learning to Love, Care and Be Compassionate; and (#8) Expanding the Imagination.

Keywords: wild pedagogies; pedagogy; environmental education; wild; anthropocene; social sciences.

RESUMEN

El concepto de ‘Pedagogías salvajes’ parece un oxímoron a primera vista. Quizás porque en Pedagogía hemos heredado cierta preferencia por lo cultivado, lo planificado, lo civilizado y lo domesticado, no es de extrañar que nuestras percepciones entren en conflicto con lo indómito o incluso con lo espontáneo, que son algunos de los atributos con que hemos definido a lo “salvaje” como un símil de lo que también yace falto de educación. Sin embargo, acotando entre un total de seis bases de datos (Education Resourcer Information Center (ERIC), Dialnet, Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), Scielo y ProQuest), se pudo comprobar que los vínculos entre la Pedagogía y lo salvaje se han actualizado recientemente en Educación Ambiental a partir del concepto de “Wild Pedagogies”. Una forma que emerge entre la literatura de Ciencias Sociales en inglés y que busca dar protagonismo a otras voces más-que-humanas para romper así con los estereotipos que han sido promovidos por las culturas occidentales y el statu quo en cuanto a la instrumentalización de la naturaleza en tiempos de paradigmas con predominancia antropocéntrica. Con ello, sus bases relacionales priorizan enfoques menos centrados en el ser humano y dicen dar paso a nuevas ontologías en educación. Este trabajo se sitúa dentro de la contextura educativo-ambiental que le da cobijo y significación teórica al término originario, además de ser una propuesta de reflexión para la Teoría de la educación como un análisis bibliográfico que converge con el nicho de reflexiones que se extraen de las que son sus seis piedras angulares hasta el año 2022: (#1) Co-profesor; (#2) La complejidad, lo desconocido y la espontaneidad; (#3) Localización de lo salvaje; (#4) Tiempo y práctica; (#5) Cambio socio-cultural; (#6) Construyendo alianzas y Comunidad Humana; y hasta el año 2024: (#7) Aprender a amar, cuidar y ser compasivo; y (#8) Ampliar la imaginación.

Palabras clave: pedagogías salvajes; pedagogía; educación ambiental; salvaje; antropoceno; ciencias sociales.

1. INTRODUCTION

Education, and more specifically Pedagogy, have been tamed in excess. Even so, the possibility of one occurring without the other is a matter of perspective. The concept comes from the Latin “domāre”, which has several definitions and contexts. It is well known that the animal is subdued, tamed and made docile with premediated efforts to exercise and teach it; that passions and disorderly conducts are also subdued and repressed; that some material objects are even tamed to give them flexibility; and that when seeking to domesticate that someone –a human–, the goal is to moderate the harshness of their character (Real Academia Española, 2022).

Many things could therefore be subjected to the demands of another’s will. However, it is worth looking in detail at the relationship between the characteristics of the other more-than-human and what is believed should be transformed or tamed. Attributes and logic associated with members of the biotic community –with flora, wildlife, the earth on which we now walk upright and, ultimately, the natural world in general– are perceived as strange. They are a danger to the dominant will. The human, who subjects other forms of being to their own, seeks to humanise and end what they consider contrary to the use of their distinguished reason. Wild is therefore: (i) of a plant, if it grows without being cultivated; (ii) of an animal, if it is not domesticated or is ferocious; (iii) of land, if it is mountainous, rugged and uncultivated; (iv) of an attitude or situation, if it is not controlled or dominated; (v) primitive and uncivilised; (vi) lacking education or even external to social norms; (vii) cruel or inhumane (Real Academia Española, 2022). These circumstances urge us to analyse fundamental aspects of the “wild” in relation to Pedagogy as well as the fact that the term has long since acquired a reputation that is contrary to anything to do with humanity. For example: could Pedagogy be wild? Let’s fit our purpose into this question, while attempting of course to forge a path through the ways of doing and thinking of the wildest and most frenzied side of this science, if possible, without running the risk of going back to its prelogical moments at least. All of this will hint at the topic we are about to present: “Wild Pedagogies” which, translated into Spanish (“Pedagogías salvajes”), has no identity in Hispanic Social Science literature. This is a stark contrast with the situation of the term in Social Science literature in English, where it has recently been developing in line with knowledge of Environmental Education1.

A certain distrust in the face of the untamed is not strange, especially when we know that many parts of Pedagogy would perish without control or systematisation. These include: the end of pedagogical action or the groove of intentionality, which leads us to a presentation of “Wild Pedagogies” that is challenging for the Theory of Education to say the least.

Wild Pedagogies2 is an approach and a project subversively inspired in the world of “the wild”, recognising it as a source of knowledge and experience, as if it were a process of self-organisation capable of generating smart systems and organisms that remain under the restrictions of –and are components of– other wild systems of greater magnitude (Jickling et al., 2018b). Therefore, its roots lie in the phenomenological current and in subjective experience; this means that the first steps to understanding the reality of education are geared towards why the natural world should be given a new role in teaching-learning processes. Suggestive nuances for assessing other forms of relational ontology in education although, in our opinion, whether they are somewhat harmful for the gnoseological foundations of Pedagogy remains to be seen.

Here lies the true systemic axis that we must highlight as “key”: education and nature, because minds –like culture– mature with the earth (Paulsen et al., 2022). For this analysis, it is therefore a good idea to “let things be done” to see what happens with this family of “wild” pedagogical concepts emerging in new postmodern literature and which each seem to have a strategic function within their characteristic order. Expressed in this way and, perhaps, with a little perspective, we will begin by presenting the word “wilderness”, which dates back to the Old English word “wildoerness”. This leads to what today we know as “Wild”, semantically analysed as follows: “wil” linked to wild or will, “doer” to beast or animal and “ness” to place or quality (Foreman, 2014, cited in Jickling et al., 2018b). This starting point reveals the meaning that devotion to nature brings to this narrativity, making it necessary to add that Wild Pedagogies seek to renegotiate an insufficient and obsolete ecological message. To achieve this, its literature is impregnated with a certain sense of romance that challenges conventions, inviting humankind to imagine what escaping the Anthropocene era would mean for education.

‘Wild’ is the participle past of ‘to will’; a ‘wild’ horse is a ‘willed’ or self-willed horse, one that has been never tamed or taught to submit its will to the will of another; and so with a man (Trench, 1853, cited in Blenkinsop & Ford, 2018a, p. 311).

So, what does Social Science literature have to say about Wild Pedagogies theory? This question obviously suggests a priority challenge to obtain innovative results in the field of Pedagogy and Environmental Education in Spain. The overall objective is therefore to analyse the pedagogical and philosophical foundations of Wild Pedagogies theory. A series of specific objectives (SO) have been defined to respond to the primary purpose: (SO1) differentiate between the role assigned to the educator and the student in Wild Pedagogies theory; (SO2) analyse the practical and ethical implications of Wild Pedagogies theory; (SO3) identify geographic and ecological factors used as a basis for Wild Pedagogies theory; (SO4) study the conceptions of the teaching-learning process proposed by Wild Pedagogies theory; (SO5) explore the educational objectives of Wild Pedagogies theory; and (SO6) identify the educational assessment conceptions that support Wild Pedagogies theory.

2. NARRATIVE LITERATURE REVIEW WITH CERTAIN SYSTEMIC INFLUENCE

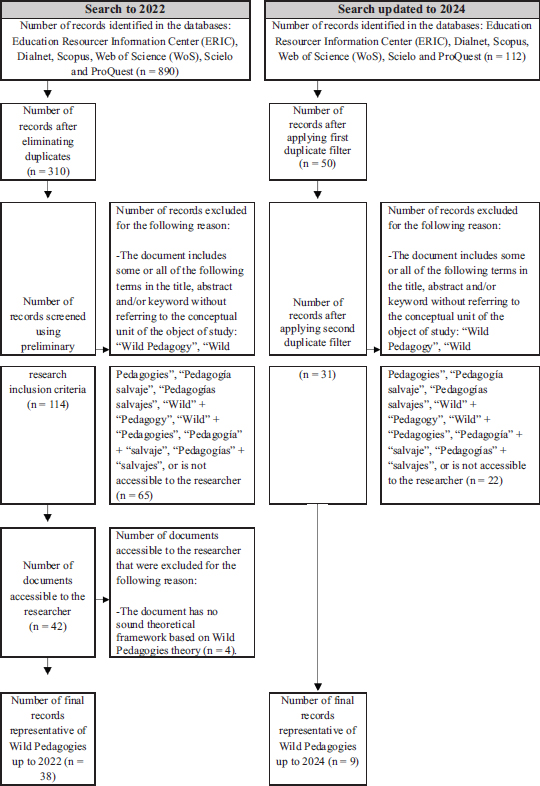

At the expense of a fuller understanding of what Wild Pedagogies means, the need to conduct a Narrative Literature Review to analyse a specific and representative sample of documents was diagnosed. Six potentially relevant Social Science databases were used to search for this output: Education Resourcer Information Center (ERIC), Dialnet, Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), Scielo and ProQuest. A total of 890 documents were initially obtained in 2022, later reduced to 310 after excluding duplicates. Preliminary mapping eligibility criteria were applied to these 310 documents3, thus leaving a total of 114 documents. A second eligibility criteria filter was added to these initial “pilot” results, the specific criteria of this narrative review. Continuing with the proposed structure, the aim was to perfect the selection strategy so as to identify documents that: i) included some or all of the following terms in the title, abstract and/or keywords referring to the conceptual unit of the object of study: “Wild Pedagogy”, “Wild Pedagogies”, “Pedagogía salvaje”, “Pedagogías salvajes”, “Wild” + “Pedagogy”, “Wild” + “Pedagogies”, “Pedagogía” + “salvaje”, “Pedagogías” + “salvajes”; ii) were accessible to the researcher; and, iii) had a sound theoretical framework based on Wild Pedagogies theory. Texts meeting these conditions up to 2022 amounted to a total of 38 results. However, the time eligibility criterion was later updated to 2024 and added to the previous batch, giving a total of 9 final results (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

FLOWCHARTS

3. WHAT WILD PEDAGOGIES SAYS AND ADDS

In order to identify possible emerging themes related with the core topic and meet the pre-established objectives, this section is sorted according to Wild Pedagogies cornerstones and/or touchstones4, which total eight up to 2024.

3.1. Stone #1 – Co-teacher (SO1)

The human teacher’s will has traditionally dominated the pedagogical scene, a conception that would not change until well into the 20th century (Quay & Jensen, 2018). An education model based on the student –also human– was first mentioned from this moment on and is still valid today (Ketlhoilwe & Velempini, 2021; Quay & Jensen, 2018; Quay, 2021). Based on these understandings, the answer to purpose number one is essential. Although various dualisms cloud our perception of the world, we are facing the conflict between the role of the subject and object, of humans and non-humans. Once the concept of “nature as Co-teacher” was proposed (Blenkinsop & Ford, 2018a; Green & Dyment, 2018; Jickling & Blenkinsop, 2020b; Jickling & Morse, 2022; Jickling et al., 2018b; Quay & Jensen, 2018; Winks & Warwick, 2021), the solution offered by Wild Pedagogies was discovered to end the androgenic trend to objectify or personify any being, entity or “matter” found behind the pedagogical process of “teaching”. In the field of anthropomorphism, Dewey explained that the child is the experimenter, “who” experiences education as the “subject”, while knowledge and curricular skills are the “what” [is learned or taught] as the “object” of that “subject” (Dewey, 1913, cited in Quay, 2021).

In view of our mission, the problem is that non-humans or, if preferred, more-than-humans, are objectified by education policy and practices in the curriculum (Matsagopane, 2024). It is even said that objects –mistakenly considered as natural– are introduced in the classroom as part of –and in part because of– Environmental Education in a dangerously reductionist way. This could be justified with the term referred to by Quay (2021) as “anthropomorphic reasoning” (p. 10). Conveying that the task of rethinking the role of all agents involved in the teaching-learning process will be in vain unless we endeavour to simultaneously and interconnectedly develop new ways of thinking Environmental Education Theory (Blenkinsop & Ford, 2018b); then will the relational, the critical and the existential dimension become forces that challenge and foster the revolution we so need. A change that will start to take shape when: (i) the human teacher actively takes a step back (Willis et al., 2024); and (ii) allows more-than-human beings to communicate with them and with the students. Something that, in the words of philosopher Nӕss (1989), would be an invitation to open up our “ecological self”.

Due to the line that marked the character of this point, we can confirm that when Wild Pedagogies conceives nature as a Co-teacher, what it is trying to say is that it takes centre stage in the teaching-learning process, leading not only to a decentralisation of roles and duties for the human teacher and students, but also abruptly introducing an ecocentric perspective (Jickling & Blenkinsop, 2020b; Jickling et al., 2018b; Kuchta, 2022; Nerland & Aadland, 2022; Quay, 2021). From this viewpoint, students need the help of a guide (the human teacher) to imagine and pseudo-experience new ways of being in the natural world (with the more-than-human teacher), without forgetting that it is the human teacher who implements their own activism as an example of their Wild Pedagogy (Jickling et al., 2018b; Kuchta, 2022). These ideas will inevitably raise issues such as the question posed by Quay (2021) in relation to renegotiating roles: “How can decentering of humans occur in education, without at the same time denying humans?” (p. 8).

3.2. Stone #2 – Complexity, the Unknown and Spontaneity (SO2)

Ecological concerns raised by posthumanism and new materialisms are complex, affecting present and future generations. Likewise, the practical and ethical implications of Wild Pedagogies in childhood and even having already proven its effectiveness with this name at university levels (Krigstin et al., 2023) are in line with reflecting the post-human shift (Jickling et al., 2018b; Maistry et al., 2023; Paulsen et al., 2022; Pierce & Telford, 2023). Highlighting some critical points in the proposals by Paulsen et al. (2022) can respond to the second purpose of this analysis:

Within this post-humanist approach, scientific and environmental educators have adopted the concerns of Donna Haraway, among others, about when species meet or what happens with companion species (Jickling & Blenkinsop, 2020a; Morse et al., 2021b; Paulsen et al., 2022).

In their conceptions of education, they incorporate agential realism ideas from the philosophy of Karen Barad and her diffractive methodology (Paulsen et al., 2022). A connection that becomes evident in the way Wild Pedagogies constantly allude to restructuring the image of nature as Co-teacher so as to create different relationships between us, and a world that is not independent of our experience (Smit & Veerbeek, 2023), such that Wild Pedagogies identifies with other ecocentric pedagogies like Friluftsliv5. While the environment is at the core of Friluftsliv pedagogy, it is striking that this pedagogy has recently been recognised as if it were part of Wild Pedagogies, or vice versa, that Wild Pedagogies is an integral part of Friluftsliv pedagogies. In fact, Friluftsliv has stated the following: “we believe we share this ecocentric perspective with Wild Pedagogies, among others through the ‘nature as a Co-teacher’ touchstone” (Nerland & Aadland, 2022, p. 121).

The influence of new materialism rhetoric about material aspects of the world is evident in literature on Wild Pedagogies, as we indirectly anticipated earlier. A Wild Pedagogies approach to poetic narrative also known as “prosopopoeia” (Quay, 2021); the human form of giving voice to the more-than-human; without forgetting that, even though we will never be able to convert, speak or think for the natural other, we can and must learn to speak and think about the problems we cause to all the living systems around us.

New “neoqualitative” educational research methods are emerging (Paulsen et al., 2022, p. 154) in the place of traditional “post-qualitative methods”. An important nuance attributed to Paulsen et al. (2022), who also mention that this phenomenological human experience is overdetermined by our intersystematicity with the more-than-human other. Our review can confirm that Wild Pedagogies seek a kind of “wilding of research” (Jickling & Morse, 2022, p. 32). With no evidence to contrast these forms of “neoqualitative” research, as well as the absence of a clear differentiation between the possible methods to which the concept refers and based on our review, we suggest that Lyrical Philosophy, Pinhole Photography and the delight of Poetry or Poetic Narrative, due to their divergence, be the reflection of the “neo” research methods they promote.

It is possible to attribute some affective theories of new materialism to Karin Hultman, Hillevi Lenz Taguchi and Simon Ceder since they have also influenced their narrative (Beeman, 2021; Jickling & Blenkinsop, 2020a, 2020b; Morse et al., 2021b; Paulsen et al., 2022). Likewise, various authors indirectly reinforce these ideas, linking them with childhood and the background of what is known in Wild Pedagogies as Aesthetic Learning Processes (ALP and/or ALPs) (Paulsen et al., 2022; Hughes, 2023). And taking as an example the concept of mimesis developed by Danish existential phenomenologist Mogens Pahuus (1988, cited in Paulsen et al., 2022), we highlight the way in which Edlev (2009, cited in Paulsen et al., 2022) refers to the imperfect imitation of material and sensitive things for the child’s environmental education.

This is therefore a complex project that invites us to an exercise of introspection towards the unknown, towards other states of Pedagogy with the natural world. This innovation refers to a specific level of alteration, i.e., to a “disruptive innovation” (Aikens, 2021; Ketlhoilwe & Velempini, 2021). Agential disorders that challenge our Western pedagogical thoughts. What’s more, some who follow Foucauldian themes have already tried to cite Wild Pedagogies to refer to somatic multiplicities and the neurobiologised educational subject (Reveley, 2024).

3.3. Stone #3 – Locating the Wild (SO3)

In 1997, American philosopher Edward S Cassey proposed that place is an immediate environment surrounding the body, which must in no way be confused with space. Thus, he reaffirmed that places are carriers of memories, narratives and emotions, which in some way warns that these places can greatly affect the psychological well-being of the Homo genus (Green & Dyment, 2018; Petersen, 2021). Some have also recently postulated that the environment is made up of two essential elements: natural, more-than-human places and built spaces, both urban and rural (Morse et al., 2021b). Quotes that are very close to the approaches that point towards the possibility of building an updated, “wild” Pedagogy among –and not only on– the natural space.

A clear example of these pedagogical adaptations to the place-world relationship is proposed by David Greenwood, promoter of place-based education, whose words are added to this analysis to shed truth on our presentation. “The placial and bodily aspects of memory invite a phenomenological description of ‘embodied implacement’, and phenomenology becomes an exploration of the body in built and wild places. Human experience, then, is the ongoing journey between places” (Cruz-Pieere & Landes, 2013, cited in Petersen, 2021, p. 50). In line with this particular aspect, Wild Pedagogies literature forges work where the place as an entity occupies a distinctive and even, one might say, central value. For this reason, many ideas by Cassey or Greenwood can be found between the lines (Aikens, 2021; Blenkinsop & Ford, 2018b; Green, 2022; Jickling & Blenkinsop, 2020a, 2020b; Jickling et al., 2018b; Jickling, 2015; Morse et al., 2018a, 2021b; Paulsen et al., 2022; Petersen, 2021).

In response to objective three, the epistemic hypothesis assumed by Wild Pedagogies about place and worlds shown as ecosystems makes its conception of the teaching-learning process somewhat more than purely experiential (Jickling et al., 2023b). This is where an important feature is reflected that separates this approach from others that are apparently similar, without denying how they may have been influenced by other alternative movements. In fact, the idea to be conveyed is that Wild Pedagogies present theses that challenge what to date has been an exclusive argument of community-based education, place-based education, ecological identity, Outdoor Education, Environmental Education and even Experiential Education. In this regard, and while still proposing something new and fascinating, it reminds us of familiar methodologies and approaches (Henderson, 2018; Winks, 2020). Something like: “The juncture between the old and the new – an intergenerational call to attentiveness, connection and action. A blending of philosophies, but a more urgent and decisive call” (Winks, 2020, p. 1). Its name evidently encompasses different renewed pedagogical formulas and it has a certain degree of common ground with other predecessor movements (Morse et al., 2021b). Some of them, which first emerged in the 1990s, suggested the importance of connecting education with the natural place, as maintained today by Wild Pedagogies.

However, to ascertain the difference brought by the nuance of the wild in this case, we must begin by travelling between these places “with a critical eye” (Jickling et al., 2018b, p. 43). Wild Pedagogies thus acknowledges that, despite not being what we might anticipate, wild places are present near our homes, in urban areas and even industrial areas (Hempsall, 2022; Jickling & Blekinsop, 2020a, 2020b; Jørgensen-Vittersø et al., 2022; Morse et al., 2018a, 2018b, 2021b; Paulsen et al., 2022). A statement that has been corroborated in multiple papers; among their most notable characteristics we find that they are neither distant (Morse et al., 2021b), uninhabited and/or deserted (Jickling et al., 2018b), nor are they intact/virgin or out of our reach (Richey, 2022). In fact, authors such as Morse et al. (2021b) suggest that, regardless of their form, they are all among us at all times. Based on such considerations, we can extrapolate to the case of places in ruins, recently recognised by Schmidt (2022) as a “type” of wild place. This last contribution proves how Wild Pedagogies embraces the beauty of wild nature in a realistic way, moving away from the stereotypical profile given to the aesthetics of the environment in the Anthropocene era (Petz, 2022).

This leads us to the underlying argument that traditional education prefers safe places, those that prioritise predictability even when this means limiting students’ pedagogical exploration. Something that often idealises and distorts learning processes as it aims to exclude wild places –more-than-human places– from education simply because they are wrongly associated with dangerous places (Beeman, 2021; Jickling & Blenkinsop, 2020a; Jickling et al., 2018b; Medeiros, 2022; Morse et al., 2021a).

3.4. Stone #4 – Time and Practice (SO4)

In truth, pedagogical activity and nature are codependent (Nerland & Aadland, 2022). When analysed together or even separately, Pedagogy and nature are two complex realities (Green & Dyment, 2018), so much so that we seldom consider all possible manifestations of nature. Paulsen et al. (2022), point out that nature exists in its material form –that we inhabit– and in its ideal form –that inhabits our thoughts–, and that both deserve exploration. So, the following was assessed: if we are going to take a step towards wild learning in nature, where other more-than-humans have a place in our conversations, then where and how we have them is extremely important (Jickling et al., 2018b; Morse et al., 2018a, 2018b). Before progressing, it is vital to reflect on some ideas chosen as “key” to respond to purpose four. Firstly, everything flourishes happily and wildly in more-than-human places and worlds where “wild education” and “wild learning” can be set up as processes of natural growth and maturing. From then:

- The concept of wild education can be found in different papers, all accompanied by strong bonds of trust between the human and more-than-human (Henderson, 2018; Jickling et al., 2018b; Ketlhoilwe & Velempini, 2021; Morse et al., 2021a; Winks & Warwick, 2021). However, wild education does not refer in a colloquial sense to “going crazy” or “being out of control” (Jickling et al., 2018b).

- It is about understanding that Wild Pedagogies theory views freedom as a state since everything points to the fact that it enables learning outcomes that are not prescribed and that co-occur with pedagogical mediation at all times (Green, 2022; Jickling & Blenkinsop, 2020b).

- Although literature features extravagant expressions and concepts that can raise certain methodological doubts –and insinuate a possible didactic free will, as in the case of “crazy” and “madness”, very frequent word in contexts that call for outdoor creativity (MacEachren, 2022)–, imaginative enrichment is fostered by a wild formulation of Pedagogy for and with Environmental Education. Linking these ideas with the context of madness reveals a type of “pedagogical abandon” (Quay & Jensen, 2018), which pushes us to move from a tamed Pedagogy (humanist) to Pedagogy with free will (wild).

- Wild learning is the result of learning that, having challenged pre-established norms and in its full wild manifestation, enriches all forms of life. By paying attention to how these conceptions about the teaching-learning process are specified in the reality of Wild Pedagogies, we observe that its practices and methods are uncommon in education, such as the case of Lyrical Philosophy, ontological experiments or Pinhole Photography for pedagogical experimentation [in], [with], [for] and [of] the wild place. Many experiences are granted the title of “experiments with wild pedagogies” (Morse et al., 2018b, p. 244). This is how Wild Pedagogies demand that we let it happen, or what other authors such as Quay and Jensen (2018) have called: unleashing “the madness of pedagogies” (p. 298)

3.5. Stone #5 – Socio-Cultural Change (SO5)

At the dawn of the 21st century, the environmental crisis follows guidelines and formulas that point to a lack of communication with the ecosystem. This lack of conversation between us and the more-than-human world highlights a deficit of ontological appreciation. Something that is historic, as it is a consequence we have been dragging since the rationalist discourse of science came to Europe in the 17th century, proposing our separation from the natural environment (Medeiros, 2022). To sum up, here we must add that the effects of individualistic or individual-centred ontology substantially intensify the severity with which these phenomena are expressed which, with prejudice, prevent or hinder processes of expansion and reconnection with nature. Of all the examples reviewed, only one, Beeman (2021), mentions the term coined by Robert Greenway to refer to these possible obstacles as “psychological barriers/limits” (p. 333). But delving deeper into this need to reconnect with nature and responding to research purpose five, we can see that Wild Pedagogies attempt to justify their objective of the idea of renaturalising teaching-learning processes according to other, more challenging structures: “The goal of wild pedagogy is ‘re-wilding’ education” (Jickling et al., 2018b, p. x).

In line with these findings, the philosophical tradition of the concept of “re-wilding” was also found to be respected within the parameters of Deep Ecology (Beavington et al., 2022; Blekinsop & Ford, 2018b; Hempsall, 2022; Henderson, 2018; Jickling & Blekinsop, 2020a, 2020b; Jickling et al., 2018a, 2018b; Jørgensen-Vittersø et al., 2022; MacEachren, 2022; Morse et al., 2021b; Nerland & Aadland, 2022; Paulsen et al., 2022; Quay & Jensen, 2018; Richey, 2022; Winks & Warwick, 2021). A type of education that invites us to an interstitial dialogue between species and ecosystems. Other authors, such as Jickling and Blekinsop (2020b), suggest that this type of learning is developed around three major cores: (1) affiliation; (2) being with more-than-human worlds; and, (3) deep listening. A purpose of re-wilding nature that hides the need to learn to be different people, to return to nature, to cohabit in harmony and in society with other living networks (Jickling et al., 2018b).

3.6. Stone #6 – Building Partnerships and Human Community (SO6)

Contemporary education, the school of today, ensures their survival by limiting themselves to assessing and controlling human subjects, their systems, structures and even routines (Aikens, 2021; Winks & Warwick, 2021). However, as noted in other sections, this idea of control is camouflaged by a dangerous notion of “safety” linked, according to Wild Pedagogies, to the idea of “domesticating” (Jickling & Blenkinsop, 2020a; Lama, 2022; Morse et al., 2021a; Winks & Warwick, 2021). So thinking, like Morse et al. (2021a), that everything contributes to a delineation of forms of being is extremely convenient given the political-ideological consistency that characterises –and sometimes in a self-absorbed way– unfortunate decision-making during the Anthropocene era. Only an education policy that is unbridled or self-willed would therefore be capable of questioning the meaning and purpose we have given to education on planet Earth (Winks & Warwick, 2021); only a policy that is sufficiently brave would be capable of questioning every predominant ideal, value and vision to thus deviate from the path set (Paulsen et al., 2022); only a theory like Wild Pedagogies, some say, can make this ideal policy wildly ecological without losing pedagogical control or, if preferred, adapting as a catalyst for the different ways of educating in contact with nature (Jickling et al., 2018b). To such an extent we could agree that some authors already propose Scotland as a reference for imagining what would be a political model that is tolerant with the type of wild education it aims to build (Winks & Warwick, 2021).

To justify the need for a wild policy change it is evident that this one-on-one with the more-than-human other will identify the need to structure our own “implicit policies” (Jørgensen-Vittersø et al., 2022) because it is well known that knowledge of the world is expressed differently when learning from nature as a Co-teacher. Understanding this means adopting a critical stance as Wild Pedagogies maintains that, if education action is contaminated by exclusively human interests, we cannot expect our notion of “assessment” to be applicable to the learning offered by the natural world. Beyond this evidence, the following questions can and should arise: “can wilding educational policy create an educational situation where students’ learning and wild places flourish together?” (Ketlhoilwe & Velempini, 2021, p. 359). The proposal thus consists in making learning in wild places possible (Green & Dyment, 2018) without forgetting that wilding educational policy has the capacity to: (i) improve the provision of wild pedagogies while supporting the creation of a curriculum aimed at educational practice in the natural environment (Ketlhoilwe & Velempini, 2021) and, (ii) address the variety of wild experiences as a student right (Ketlhoilwe & Velempini, 2021) given that it offers a positive response to inherent tensions between the school –formal education institution– and nature –“the wild”–, proposing a substantial improvement in their relationship (Aikens, 2021).

3.7. Exploring the latest developments on Wild Pedagogies: Stones #7 and #8

Wild Pedagogies was based on a total of six cornerstones until 2022, but two more were added in 2023: (#7) Learning to Love, Care and Be Compassionate and (#8) Expanding the Imagination (Jickling et al., 2023a). In stone seven, Learning to Love, Care and Be Compassionate, references to Rachel Carson and her monumental work Silent Spring are an important axis for reflecting on affectivity and empathy in the reciprocal care between humans and nature. While stone eight, Expanding the Imagination, calls for public education and the challenge of expanding anthropocentric imagination that limits itself. But the document cited does not arise precisely from the systematisation of the previous literature search, it is a reference added by the authors and following a conversation with Bob Jickling, Professor Emeritus at Lakehead University (Canada), one of the most well-known representatives of this literary body. From this recent thematic update, we know that, at least to date, this brave voice is still latent6.

4. CONCLUSIONS

Wild Pedagogies aimed to contribute to debate on the possibility of updating some ontological conceptions in education; up to 2024, its attempts were expressed in a total of eight touchstones. Each one warns of the need to explore other, bolder ways of facing more ecological and ecocentric relational prospects.

Whether we agree more or less with what the most representative authors defend at theoretical and/or conceptual level, especially considering what Education Theory has always said about our bases and who the subject of education is, there is no doubt that everything revolving around the concept is presented as an opportunity to closely examine the anthropocentric thought systems that prevail in our educational processes. This does not exempt us from focusing on the gnoseological minimums that should not be overlooked, not even when talking about the future of nature in relation with Pedagogy. A stir that also stems from unresolved conflicts between subject–object and human–more-than-human which, along with new philosophical realisms, are introduced as some of the criticisms posed by this approach to education in general, especially those directly affecting the epistemological, ontological and even axiological bases of “traditional” educational models. These are precisely the reasons that justify the need to continue exploring what Wild Pedagogies have to offer our systems.

Closely following this type of post-humanist project, which claims to be untameable, would enable us to gain a more detailed understanding of what we are facing in the Anthropocene era. So far, we know that our challenges are complex and that problems on planet Earth will not be solved any old way. However, we are offered a somewhat unique alternative to attempt to see where we should direct the change of perspective if we wish, as has been claimed, to let Pedagogy loose in the natural world.

FUNDING

Project title: Analysis of the processes of (dis-re) connection with nature and technology when building a child’s identity (NATEC-ID).

Reference: PID2021-122993NB-I00. Ministry of Science and Innovation. PI: José Manuel Muñoz Rodríguez.

REFERENCES

Aikens, K. (2021). Imagining a wilder policy future through interstitial tactics. Policy Futures in Education, 19(3), 269-290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210320972578

Beavington, L., Beeman, C., Blenkinsop, S., Heggen, M., & Kazi, E. (2022). The paradox of wild pedagogies: loss and hope next to a norwegian glacier. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 25, 37-54. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1704

Beeman, C. (2021). Wilding liability in education: Introducing the concept of wide risk as counterpoint to narrow-risk-driven educative practice. Policy Futures in Education, 19(3), 324-338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210320978096

Blenkinsop, S., & Ford, D. (2018a). Learning to speak Franklin: nature as co-teacher. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(3), 307-318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-018-0028-3

Blenkinsop, S., & Ford, D. (2018b). The relational, the critical, and the existential: three strands and accompanying challenges for extending the theory of environmental education. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(3), 319-330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-018-0027-4

Cruz-Pierre, A., & Landes, D. A. (Eds.).(2013). Exploring the work of Edward S. Casey: Giving voice to place, memory, and imagination. Bloomsbury Academic.

Edlev, L. T. (2009). Naturopplevelse og naturfaglig interesse. Hva er forholdet mellom æstetiske læreprosesser og naturfaglig undervisning? En K. Fink-Jensen & A. M. Nielsen (Eds.), Æstetiske læreprocesser – i teori og praksis (pp. 13-28). Billesø & Baltzer.

Foreman, D. (2014). The Great Conservation Divide: Conservation Vs. Resourcism on America’s Public Lands. Raven’s Eye Press.

Green, C. (2022). The slippery bluff as a barrier or a summit of possibility: Decolonizing wild pedagogies in alaska native children’s experiences on the land. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 25, 83-101. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1714

Green, M., & Dyment, J. (2018). Wilding pedagogy in an unexpected landscape: reflections and possibilities in initial teacher education. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(3), 277-292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-018-0024-7

Hempsall, C. (2022). Is the theory of Wild Pedagogies precisely the utopian philosophy the Anthropocene needs? Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 25, 222-236. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1662

Henderson, B. (2018). Review of wild pedagogies: touchstones for re-negotiating education and the environment in the Anthropocene by B. Jickling, S. Blenkinsop, N. Timmerman, M. De Dannan Sitka-Sage (Eds.), Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(3), 331-335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-018-0025-6

Hughes, F. (2023). Early Childhood Educators’ Professional Learning for Sustainability Through Action Research in Australian Immersive Nature Play Programmes 1. Educational Research for Social Change, 12(1), 69-83. https://doi.org/10.17159/2221-470/2023/v12i1a6

Jickling, B. (2015). Self-willed learning: experiments in wild pedagogy. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 10(1), 149-161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-014-9587-y

Jickling, B., & Blenkinsop, S. (2020a). Wilding teacher education: responding to the cries of nature. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 23(1), 121-138. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1633

Jickling, B., & Blenkinsop, S. (2020b). Wild pedagogies and the promise of a different education. Challenges to change. En D. Wright & S. Hill (Eds.), Social Ecology and Education: Transforming Worldviews and Practices (pp. 55-64). Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781003033462-5

Jickling, B., & Morse, M. (2022). Experiments with Lyric Philosophy and the wilding of Educational Research. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education (CJEE), 25, 13-36. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1712

Jickling, B., Blenkinsop, S., & Morse, M. (2023a). An introduction to wild pedagogies. En S. Priest, S. Ritchie & D. Scott (Eds.). Outdoor Learning in Canada http://olic.ca

Jickling, B., Morse, M., & Blenkinsop, S. (2023b). Wild Pedagogies, Outdoor Education, and the Educational Imagination. International Explorations in Outdoor and Environmental Education, 12, 183-198. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-29257-6_12

Jickling, B., Blenkinsop, S., Morse, M., & Jensen, A. (2018a). Wild pedagogies: six initial touchstones for early childhood environmental educators. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 34(2), 159-171. https://doi.org/10.1017/aee.2018.19

Jickling, B., Blenkinsop, S., Timmerman, N., & Sitka-Sage, M. (Eds.). (2018b). Wild pedagogies: Touchstones for re-negotiating education and the environment in the anthropocene. Springer International Publishing AG. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90176-3

Jørgensen-Vittersø, K. A., Blenkinsop, S., Heggen, M., & Neegaard, H. (2022). «Friluftsliv» and wild pedagogies: building pedagogies for early childhood education in a time of environmental uncertainty. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 25, 135-154. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1713

Ketlhoilwe, M. J., & Velempini, K. (2021). Wilding educational policy: the case of Botswana. Policy Futures in Education, 19(3), 358-371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210320986350

Krigstin, S., Cardoso, J., Kayadapuram, M., & Wang, M. L. (2023). Benefits of Adopting Wild Pedagogies in University Education. Forests, 14(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/f14071375

Kuchta, E. C. (2022). Rewilding the imagination: teaching ecocriticism in the change times. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 25, 190-206. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1696

Lama, N. (2022). An inquiry into education and well-being: perspectives from a himalayan contemplative tradition and wild pedagogies. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 25, 70-82. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1794

MacEachren, Z. (2022). Reflections on campfire experiences as wild pedagogy. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 25, 102-119. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1706

Maistry, S. M., Sabelis, I., & Simmonds, S. (2023). Invoking posthuman vistas: A diffractive gaze on curriculum practices and potential. South African Journal of Higher Education, 37(5), 78-99. https://doi.org/10.20853/37-5-5988

Matsagopane, Y. (2024). Imagining Advancement of Wilding Educational Policy: Reflections and Possibilities in Botswana. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 40, 48-54. https://doi.org/10.1017/aee.2024.4

Medeiros, S. (2022). Listening to the Jaguar and the Tapir. An outline of a wild pedagogy. Literature Beyond the Human, 146-159. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003243991-12

Morse, M., Blenkinsop, S., & Jickling, B. (2021a). Wilding educational policy: Hope for the future. Policy Futures in Education, 19(3), 262-268. https://doi.org/10.1177/14782103211006649

Morse, M., Jickling, B., Blenkinsop, S., Morse, P. (2021b). Wild Pedagogies. En G. Thomas, J. Dyment & H. Prince (Eds.), International Explorations in Outdoor and Environmental Education (pp. 111-121). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75980-3_10

Morse, M., Jickling, B., & Morse, P. (2018a). Views from a pinhole: experiments in wild pedagogy on the Franklin River. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(3), 255-275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-018-0021-x

Morse, M., Jickling, B., & Quay, J. (2018b). Rethinking relationships through education: wild pedagogies in practice. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(3), 241-254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-018-0023-8

Naess, A. (1989). Ecology, Community and Lifestyle: Outline of an Ecosophy. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511525599

Nerland, J., & Aadland, H. (2022). Friluftsliv in a Pedagogical Context. A Wild Pedagogy Path toward Environmental Awareness. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 25, 120-134. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1698

Pahuus, M. (1988). Naturen og den menneskelige natur [Nature and human nature]. Philosophia.

Paulsen, M., Jagodzinski, J., & Hawke. S. (Eds.). (2022). Pedagogy in the anthropocene: Re-wilding education for a new earth. Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90980-2

Petersen, K. (2021). Reflections on place, place-based education and wild pedagogies in Denmark: a Schooner Project. Journal of the International Society for Teacher Education, 25(1), 48-61. https://doi.org/10.26522/jiste.v25i1.3657

Petz, M. (2022). Nomadtown, manifesting the global village hypothesis: a case study of a rural resilience hub within an educational milieu in North Karelia, Finland. European Countryside, 14(1), 180-216. https://doi.org/10.2478/euco-2022-0010

Pierce, J., & Telford, J. (2023). From McDonaldization to place-based experience: Revitalizing outdoor education in Ireland. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2023.2254861

Quay, J. (2021). Wild and willful pedagogies: education policy and practice to embrace the spirits of a more-than-human world. Policy Futures in Education, 19(3), 291-306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210320956875

Quay, J., & Jensen, A. (2018). Wild pedagogies and wilding pedagogies: teacher-student-nature centredness and the challenges for teaching. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(3), 293-305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-018-0022-9

Real Academia Española. (2022). Diccionario de la lengua española https://www.rae.es/

Reveley, J. (2024). Somatic multiplicities: The microbiome-gut-brain axis and the neurobiologized educational subject. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 56(1), 52-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2023.2215427

Richey, M. (2022). Transforming existing perceptions: language as a tool for accessing the ecological self. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 25, 207-221. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1701

Schmidt, J. (2022). The place of ruin within wild pedagogies. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 25, 55-69. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1703

Smit, P.-B. & Veerbeek, I. (2023). Parrēsia beyond Humankind? Exploring the Representation of the Voice of Creation in the Epistle to the Romans. Journal of Early Christian History, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/2222582X.2023.2254022

Trench, R. C. (1853). On the Study of Words. Macmillan.

Willis, A., Thiele, C., Fox, R., Miller, A., McMaster, N. Menzies, S. (2024). Educators unplugged: Working and thinking in natural environments. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2024.2324795

Winks, L. (2020). Wild Pedagogies. Environmental Education Research, 26(2), 303-304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1688766

Winks, L. & Warwick, P. (2021). ‘From lone-sailor to fleet’: Supporting educators through Wild Pedagogies. Policy Futures in Education, 19(3), 372-386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210320985706

1 Based on preliminary literature mapping results, which confirmed that the translation of the independent terms of the concept of Wild Pedagogies in Spanish (singular and plural), i.e.: Pedagogía, salvaje, Pedagogías and salvajes, are linked with the theme of Aveyron, the feral child, and not with Environmental Education.

2 Here we recognise the work of the group comprised of: Hebrides, I., Ramsey Affifi, Sean Blenkinsop, Hans Gelter, Douglas Gilbert, Joyce Gilbert, Ruth Irwin, Aage Jensen, Bob Jickling, Polly Knowlton Cockett, Marcus Morse, Michael De Danann Sitka-Sage, Stephen Sterling, Nora Timmerman and Andrea Welz, identified as the “Crex Crex Collective”; a taxonomical name referring to the migratory bird commonly known as the “corn crake”. Together, they officially began literature on Wild Pedagogies in 2018 (Jickling et al., 2018b) and the first colloquium on Wild Pedagogies on the waters of the Yukon river (Canada) in summer 2014, entitled: “Wild Pedagogies: A Floating Colloquium”. Today, their work inspires part of the educational and scientific community to consider the foundations of pedagogy in relation to the wild

3 Several aspects stand out in the literature mapping eligibility criteria: i) the documents include some or all of the following terms in the title, abstract and/or keywords: “Wild Pedagogy”, “Wild Pedagogies”, “Pedagogía salvaje”, “Pedagogías salvajes”, “Wild” + “Pedagogy”, “Wild” + “Pedagogies”, “Pedagogía” + “salvaje”, “Pedagogías” + “salvajes”; ii) that they are addressed from the area of knowledge of Social Science and develop lines related to the subject of study; iii) that they were published before 28 November 2022.

4 According to the Crex Crex Collective, cornerstones or touchstones are the core issues or topics that guide the reflections and concerns on which Wild Pedagogies literature is based. They are listed from 1 to 8 and generally preceded by a #.

5 Friluftsliv, a term deeply rooted in Scandinavian culture, was popularised by Norwegian playwright and poet Henrik Ibsen in the 19th century. Translated as “life outdoors”, it aims to promote a connection with nature through outdoor activities to favour physical and mental well-being. This lifestyle does not intend to only do sports or recreational activities, rather it favours a philosophy that emphasises simplicity, sustainability and respect for the natural environment.

6 I would like to use this footnote to thank and acknowledge the work of Professor Bob, whose vision has inspired me to objectively and lovingly reflect on this line of work that I trust can unite Environmental Education and Education Theory in a constructive debate on tasks related to ontological agencies and risks that are also necessary today for a joint understanding of matters of sustainability (including gnoseological).