ISSN: 1130-3743 - e-ISSN: 2386-5660

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.26953

THE ROLE OF KNOWLEDGE IN TEACHER AGENCY: A THEORETICAL MODEL FOR UNDERSTANDING1

El papel del conocimiento en la agencia docente: un modelo teórico de comprensión

Macarena VERÁSTEGUI MARTÍNEZ*, Jorge ÚBEDA GÓMEZ**

* Fundación Promaestro

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Spain.

macarena.verastegui@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9062-1630

** Fundación Promaestro

Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Spain.

jubeda@promaestro.org

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9286-6247

Date of receipt: 16/07/2021

Date accepted: 23/11/2021

Date of online publication: 01/03/2022

How to cite this article: Verástegui Martínez, M., & Úbeda Gómez, J. (2022). The Role of Knowledge in Teacher Agency: A Theoretical Model for Understanding. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 34(2), 237-255. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.26953

ABSTRACT

Teacher knowledge is a fundamental subject in educational research as there is evidence for its impact on the improvement of educational systems. However, most of the published research provides a partial and incomplete view of this question, as it features research models of limited effectiveness or ones that distort the concept studied. To overcome these constraints and effectively study teacher educational knowledge, it is necessary to start from a teacher-agency focus, which enables us to understand clearly what professional practice comprises. The aim of this article is to offer a theoretical and methodological model that links teacher agency to the educational knowledge that teachers are capable of producing. To do so, we have done critical-reflective work on the existing documentation and the concepts in play, starting from two models for understanding: the model of the Pedagogical Content Knowledge Summit (Helms, & Stoke, 2013) and the ecological model of Priestley et al. (2015) regarding teacher agency. As a result, we offer a model that links the concepts of teacher agency and teacher knowledge, and which expands understanding of teacher knowledge by adding two dimensions to it: (1) knowledge that teachers acquire and possess; and (2) knowledge that teachers produce within and outside the profession. Our consideration of this model involves observing whether it is useful for studying the educational knowledge that teachers are capable of creating through reflective and collaborative practices and for positioning in a more productive space the inherited classic gap between theory and praxis.

Keywords: pedagogical content knowledge; praxis; reflective teaching; observation; communities of practice

RESUMEN

El conocimiento del profesorado es un objeto de estudio fundamental para la investigación educativa desde que existe evidencia del impacto que tiene en la mejora de los sistemas educativos. Sin embargo, la mayoría de las investigaciones desarrolladas presentan una visión parcial e incompleta sobre esta cuestión, ya que ofrecen modelos de indagación poco operativos o que sesgan el constructo estudiado. Para superar estas limitaciones y estudiar de manera operativa la cuestión del conocimiento educativo docente es esencial partir de un enfoque de agencia del profesorado que permita comprender con claridad en qué consiste la práctica profesional. El objetivo de este artículo es ofrecer un modelo teórico y metodológico que vincule la agencia del profesorado con el conocimiento educativo que el docente es capaz de producir. Para ello hemos desarrollado un trabajo crítico-reflexivo sobre la documentación existente y los conceptos en juego, partiendo de dos modelos de comprensión: el modelo de la cumbre del Conocimiento de Contenido Pedagógico (Helms & Stokes, 2013) y el modelo ecológico de Priestley et al. (2015) sobre la agencia. Como resultado, ofrecemos un modelo que recoge el concepto de agencia y de conocimiento docente y que amplía la comprensión de este último constructo a partir de la inclusión de dos dimensiones: (1) el conocimiento que adquiere y posee y (2) el conocimiento que produce ad intra y ad extra de la profesión. Nuestra prospectiva con este modelo es observar si nos sirve como marco operativo para indagar el conocimiento educativo que el docente es capaz de producir en las prácticas reflexivas y colaborativas y situar en un espacio más productivo la clásica separación heredada entre teoría y praxis.

Palabras clave: Conocimiento de contenido pedagógico; praxis; enseñanza reflexiva; observación; comunidades de prácticas

1. INTRODUCTION

Since 1980, the knowledge of teachers has been a very important line of research (Biesta et al., 2017; Fernández, 2014), its main aim being to understand what this knowledge is and what it comprises. Shulman (1987) was one of the first authors to tackle this question (Biesta et al., 2017). Although, since the beginning, research has considered not only what this knowledge comprises but also how teachers are capable of generating it, most of the work done has started from a static idea of the construct, in other words, treating it as a phenomenon gained on the basis of training and professional experience (Fernández, 2014).

The models based on a dynamic idea of knowledge, like Shulman’s (1987) and that of the Pedagogical Content Knowledge Summit (PCK) (Helms & Stokes, 2013), start from a focus in which teacher knowledge is produced and expanded while carrying out teaching practice. Nonetheless, this construction of educational knowledge is limited to within the profession, in other words, it reflects how teachers add the body of knowledge needed to do their work to their initial know-how on the basis of training they receive, their working context, and the learning achievements of the students. Accordingly, teachers develop a broad body of knowledge that comprises PCK (Medina, 2006).

This focus on PCK as a construct that is created and expanded through teaching praxis is set out clearly in the model of Helms and Stokes (2013). During the PCK Summit, these researchers made an effort to combine the different pre-existing models relating to this question into an accepted unified model to act as a framework for understanding this construct. Nonetheless, this model limits itself to production of knowledge within the teaching profession, and so the view of the teacher as someone who creates educational knowledge that is projected outside of the profession does not appear in the literature relating to this line of research.

Despite this, the question of the teacher as creator of knowledge that has an effect outside the profession is not new and many authors view the profession in this way (Domingo, 2020; Rupérez, 2014; Shulman, 1987; Zeichner & Liston, 1996). This question has been given considerable attention in the field of action research as it starts from the idea of the teacher as an agent who participates in research and not just as the research subject (Kemmis, 2006), and so it appears to be one of the best ways for the teacher, along with the research team, to generate educational knowledge. Nonetheless, although this has been shown to be an effective model, teachers have other ways, closer to their work, of exploring their practice that also enable them to produce educational knowledge (Croll, 1995; Groundwater-Smith et al., 2016; Reis-Jorge, et al., 2020).

From this outlook, much of the literature has focussed on tackling this question from the perspective of the processes needed for teachers to create educational knowledge. As a result, there is a large amount of literature on the importance of reflection for teachers to become researchers in their practice (Domingo, 2020; Reis- Jorge et al., 2020; Villar Angulo, 1995), on observation so that teachers can collect evidence about the educational practice they perform (Burgess et al., 2019; Firestone & Donaldson, 2019; Roth et al., 2019), on the importance of belonging to professional learning communities (Malpica, 2013; Moreno, 2018), and on teachers’ capacity to systematise the evidence collected from practice and compare it with evidence from educational research (Croll, 1995; Malpica, 2013; Murillo et al., 2017; Perines, 2018).

In addition, other research has focussed not so much on how knowledge is produced but on its source. In this sense, teachers are the producers of the knowledge generated in their educational practice (Schön, 1984; Shulman, 1987). As this is a practical reality, theory of action is the theoretical framework from which this construct has been approached, with one of its main objectives being to understand what teachers’ praxis comprises (Dewey, 1933; González, 1997; Priestley et al., 2015). While it is true that there have been notable advances in the understanding of this phenomenon, some questions still remain to be clarified that directly affect how the teaching profession is understood (Groundwater-Smith et al., 2016; Medina & Pérez, 2017; Perines, 2018; Viñao, 2018).

Pragmatism has been a decisive philosophical influence on educational thought throughout the 20th century (Biesta, 2007; Dewey, 1933; Thoilliez, 2013), helping provide an understanding of what the teaching profession and educational practice comprise (Leijen et al., 2020). In this regard, the research by Priestly et al. (2015), built on pragmatist foundations, makes a notable contribution, incorporating the ecological focus into the description of teacher agency. From this focus, an understanding of agency is obtained on the basis of the interactions between its various elements (individual effort, available resources, and contextual and structural factors). It is through this idea of the interrelation between the elements that the contextual keys, which have little prominence in earlier literature, come to play a key role in this focus, as they are necessary to achieve an in-depth, tailored understanding of teaching praxis and, therefore, of teachers’ professional capacity to take decisions and act to benefit students’ learning process (Groundwater-Smith et al., 2016).

Nonetheless, we still do not have a unified model that integrates the capacity of teachers to construct knowledge both within the profession (a body of knowledge that teachers generate and incorporate) and outside it (educational knowledge that teachers transfer to the rest of the community) (Biesta, et al., 2017). In other words, the production of educational knowledge by teachers is a dynamic and transversal dimension of agency.

The aim of this work is to provide a theoretical and methodological model that links teacher agency to the educational knowledge that teachers can produce. To do so, we start from two models of comprehension. Firstly, the model from the PCK Summit (Helms & Stokes, 2013) of the knowledge that teachers possess. Secondly, the ecological focus of Priestley et al. (2015) on teacher agency (following the expanded version of Leijen et al., 2020) and, therefore, on how knowledge is implemented in practice. Drawing on these two models, the dynamic of production of educational knowledge by teachers is incorporated, taking into account the processes that have been identified as fundamental for this construction: reflection, observation, discussion, and systematisation.

To do this, we have followed the reading, thinking and writing method (Trilla, 2005 cited in Thoilliez, 2013), based on reflexive work involving a careful exercise of reading and documentation that has made it possible to develop an understanding and a critical discussion of the concepts in play. As a result, we offer a model that synthesises and brings together the concepts of teacher agency and teacher knowledge, and expands the understanding of teacher knowledge by incorporating both dimensions of teachers’ educational knowledge: (1) knowledge that teachers acquire and possess; and (2) knowledge that teachers produce within and outside the profession.

2. THE POTENTIAL OF REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

Within professions, and especially in teaching, reflection has been defined through the concept of reflective practice, with the incorporation of this concept into the world of education beginning with Dewey (1933). However, this concept is especially important when political agendas and research make teachers essential agents in the quality of education (Rupérez, 2014). Reflection by teachers on their practice becomes one of the key factors for improving education and one of the vital processes for strengthening the profession (Rupérez, 2014; Verástegui, 2019).

We can, therefore, understand reflective practice as the capacity to develop pedagogical judgement that makes it possible to approach educational reality in a critical, well thought-through, shared and systematic way, with the aim of approaching it adequately, creating knowledge of one’s own professional activity and seeking ways to improve it (Domingo, 2020; Schön, 1984; Zeichener & Liston, 1996).

From this framework, various authors have researched reflexive practice, considering its types and levels with the aim of understanding how it boosts teachers’ agency and encourages the creation of educational knowledge (Leijen et al., 2020; Villar Angulo, 1995).

The model of understanding we propose starts from two fundamental contributions regarding reflexive practice and its relationship with educational knowledge: Schön’s typology (1984) and the expanded model of teacher agency of Leijen et al. (2020). Firstly, Schön’s distinction (1984) regarding practical thought (knowing in action, reflection in action, and reflection on action) is still one of the most notable typologies on this question. We also accept the expansion of the work of this author that Killion and Todnem (1991) carried out, adding reflection for action, through which the projective dimension of action is incorporated. Secondly, the model of Leijen et al. (2020) links levels of reflection with the achievement of agency.

The levels of reflection mentioned form part of a continuum (Domingo, 2020) that ranges from the use of tacit and implicit knowledge to the sharing of a rigorous and systematised knowledge of educational practice (Killion & Todnem, 1991; Villar Angulo, 1995). This levelling fundamentally depends on how reflexive practice is carried out and what is obtained from it, in other words, what agency is achieved and what type of educational knowledge is mobilised and implemented (Leijen et al., 2020). To understand this question, it is necessary to pay attention to the professional dynamics in play, as well as the tools used (Domingo, 2020). For this reason, in the comprehension model we collect three professional dynamics aimed at achieving a level of reflection that fosters the creation of systematic and explicit educational knowledge: observation, discussion, and systematisation of practice with other teachers (Malpica, 2013; Úbeda, 2018; Verástegui, 2019; Villar Angulo, 1995).

2.1. The gaze that improves: observation of educational practice

Firstly, rigorous and systematic observation of educational practice is one of the essential tools for reflective practice if the objective is to create educational knowledge that can be transferred to the rest of the system (Contreras & Pérez de Lara, 2010; Leijen et al., 2020; Roth et al., 2019). Observation being systematic means, as Úbeda observes (2018, p. 5), that: (i) it is done in accordance with aims directed at improvement; (ii) it fits observation criteria drawn up by the teachers; (iii) it is done using various tools that facilitate observation; and (iv) it occupies a specific space in classroom time.

Systematic observation of practice should be incorporated both in its individual dimension –self-observation– and its professional dimension – peer observation (Spencer, 2014). Thanks to it, reflection takes shape over time, because it formulates educational objectives to achieve that relate to specific practices and it determines the channels that make it possible to systematise observation (Úbeda, 2018). In this way, teachers can reduce bias in the subsequent evaluation of educational practices and obtain evidence about what does and does not work in the classroom (Burgess, et al., 2019; Firestone & Donaldson, 2019; Roth et al., 2019; Spencer, 2014). Observation therefore makes it possible to approach practice with the aim of researching it (Contreras & Pérez de Lara, 2010; Croll, 1995; Domingo, 2020).

On these lines, many authors have underscored the need for teachers to be capable of doing research in the classroom to assess the effectiveness of their practices and to be capable of detecting where there is a need for improvement (Contreras & Pérez de Lara, 2010; Domingo, 2020; Groundwater-Smith et al., 2016; Reis- Jorge et al., 2020; Zeichner & Liston, 1996). Observation understood as a process of collecting information is vital for carrying out research in the classroom and so for creating knowledge with the aim of improving the quality of the teaching–learning process (Croll, 1995; Domingo, 2020; Malpica, 2013).

This observation can be done in various ways. However, for teachers to increase their agency and produce knowledge, participation by other colleagues is necessary, either directly (peer observation) or indirectly (recording sessions) (Spencer, 2014). In this way we come to recognise the importance of the professional community and of discussion as a fundamental dynamic for knowledge creation by teachers.

2.2. The professional community: the role of colleagues in educational debate

The processes of reflection and observation that are typical of enquiry in the classroom must be framed within a professional learning community (Malpica, 2013; Moreno, 2018; Moya & Luengo, 2019; Spencer, 2014; Villar Angulo, 1995). Teacher knowledge derives from educational experience built collaboratively in school settings to meet the educational needs of students more precisely (Contreras & Pérez Lara, 2010; Úbeda, 2018).

As we have argued, the individual capacity of the teacher plays a fundamental role when achieving agency and building knowledge of one’s practice. However, it is only one of the elements involved, as structural, social and material questions also influence these processes (Leijen et al., 2020; Priestley et al., 2015). Therefore, it is important to focus one’s gaze on the professional community and establish which actions are important from the perspective of this collective and institutionalised dimension of the teaching profession (Malpica, 2013; Moya & Luengo, 2019). This information is key when political decisions can support or disincentivise teachers in achieving agency (Biesta et al, 2017; Priestley & Drew, 2019) and, ultimately, as we argue in this article, in constructing educational knowledge (Groundwater-Smith et al., 2016; Moreno, 2018).

The capacity of teachers to build knowledge requires a collegial vision of the degree of evidence for the available educational practices and theories that guide practice in the classroom and educational centre (Malpica, 2013). With this objective, it is vital to have spaces and times in the school setting for teachers to discuss such evidence and, through observation, be capable as a group of discerning which pedagogical processes currently give the best results in their students’ learning (Priestley & Drew, 2019).

Ultimately, collegial educational discussion enables the teaching profession to improve its pedagogical judgement, put in place a high-impact professional culture, and foster continuous learning aimed at improvement (Biesta, 2007; Priestley & Drew, 2019). Nevertheless, it must be systematic and systematised if it is to be an institutionalised professional action and not just an arbitrary one (Malpica, 2013; Úbeda, 2018). This last requirement completes the cycle of knowledge construction, on the one hand incorporating a dynamic that is internal to the profession and, on the other, permitting its transfer to the rest of the educational system.

2.3. The systematisation of educational practice: a preliminary step before transfer

The systematisation of educational practice is fundamental for creating knowledge on the basis of it and so being able to institutionalise and share it (Groundwater- Smith et al., 2016). Such systematisation is done on the basis of collaborative and contextualised processes that reveal a high level of achievement in the agency of the teaching team involved (Malpica, 2013; Verástegui, 2019).

Firstly, systematisation requires shared and objective criteria that make it possible to establish what works best in the classrooms in relation to the teaching–learning processes used in the schools (Malpica, 2013; Úbeda, 2018). Knowledge about what does and does not work in each school makes it possible to improve practice, create a collaborative culture of continuous learning, and also institutionalise the educational practices that work best (Verástegui, 2019). In this way, all of the teachers in a school will work on the basis of a shared outlook and focus, collaboratively accepting the challenge of ensuring all of the students’ learning (Biesta, 2007). That is to say, it would enable teachers to achieve effective performance, approaching the task of ensuring that all of the students learn and acquire the competences that the educational institution considers essential (Malpica, 2013).

Secondly, the professional assessment criteria put teaching profession in a position of greater authority with regards to the community and the educational system (Úbeda, 2018); through the evidence generated on the basis of its practice, it can set out how it has responded to the needs of the school and what is the value of these educational responses, something that involves contributing knowledge that is necessary for the educational system as a whole. This information is of vital importance for school leaders as it will enable them to put the organisational dimension of schools at the service of pedagogy (Malpica, 2013). Similarly, educational decision makers from the political sphere should embrace this information as a valuable asset for fitting political and administrative measures to the pedagogical needs of the educational centres (Biesta et al., 2019; Viñao, 2018). Finally, academic and disciplinary research could direct part of their interest towards corroborating and exploring the evidence from teachers (Murillo et al., 2017; Perines, 2018), to provide a balance between research and practice, fostering a process of continuous feedback between them (Croll, 1995).

3. PRAXIS AS A KEY CONCEPT: THE TEACHING AGENCY

Praxis is a complex construct, and defining it is an ongoing epistemic challenge, especially when we aim to understand what type of practice teaching is and what it comprises (Medina & Pérez, 2017; Perines, 2018; Viñao, 2018; Zeichner & Liston, 1996). Despite this, a number of authors have tackled this question, making efforts to define and delineate the concept (Dewey, 1933; González, 1997; Leijen, et al., 2020).

In this article, we use the concept of agency provided by Priestly et al. (2015), which proceeds from pragmatism, to consider the question of teaching praxis. Its main contribution is the addition of the ecological focus to the theory of action, in other words, adding to our understanding of teaching action, the interaction between the various elements that comprise it. By agency we mean the overall professional capacity of the teacher that emerges from the interaction between teachers’ capacity to formulate possibilities for action, active consideration of such possibilities and the exercise of choice, and contextual factors, that is to say, the social, material and cultural structures that influence human behaviour (Priestley et al., 2015, p. 23). Therefore, teaching agency is “both a temporal and a relational phenomenon; it is something that occurs over time and is about the relations between actors and the environments in and through which they act” (Biesta et al., 2017, p. 40).

This concept of agency can be found in other authors, for example in the theory of action set out by González (1997), in which he breaks praxis down into four concepts (acts, actions, deeds, and activities). The last of these, activity, is the one that enables “authors” (“actors” in the case of Priestley et al., 2015) to choose a deed (meaningful action) from among various possibilities.

The model of agency of Priestly et al. (2015) not only includes individuals’ capacities as a core element of it, but also how this capacity interacts with other factors (contextual, biographic, etc.). Therefore, they understand agency to be a phenomenon that is achieved in and through contexts, in other words, it cannot be understood without taking into account the interactions between the different dimensions that comprise it. There are three of these dimensions: the iterational, the projective and the practical-evaluative (Priestley et al., 2015).

Firstly, the iterational dimension comprises previous experience (both personal and professional), in other words, individual capacity (skills and knowledge), of beliefs and values. In it, mental schemas are created that make it possible to act with a certain “habitus” and, therefore, perform professionally in an appropriate way, as well as to design and direct educational practice on the basis of the knowledge acquired in their period of initial training and throughout their professional careers.

Secondly, the projective dimension, influenced directly by the previous dimension, is linked to the goals that guide practice towards the creation of a different future (Priestley et al., 2015). The goals pursued have an influence when taking decisions in practice and are linked to teachers’ values and beliefs. It is vital to take into account how mechanisms for evaluating performance play a vital role when shaping professional aims, which tend to fit in with social norms and expectations. This statement leads to appraisal of what type of policies are developed in the long term to influence the projective dimension of teachers, ultimately in order to benefit the students (Priestley et al., 2015).

Thirdly and finally, teaching agency includes the practical-evaluative dimension, in other words, the one that focusses on the present and occurs in the workplace. That is to say, the perceptions and interpretations that teachers create on the basis of the cultural, structural, and material conditions in which they do their work and, on the facilities, limitations, and resources available to them (Leijen et al., 2020). This is why this dimension has a great influence on the achievement of agency as it profoundly shapes the dimensions and action of the teacher, fostering or inhibiting agency. On the one hand, it allows teachers to know what is possible in practical terms in a given situation, and on the other, it enables them to evaluate the challenges that exist in that situation and the possibilities for action in each of them (Priestley et al., 2015).

Ultimately, the fundamental contribution of these authors is to offer an ecological focus on the conceptualisation of agency. In other words, they see it not only as individuals’ capacity to act, but also as a phenomenon they achieve in and within contexts that continuously change over time and are directed towards the past, future, and present (Priestley et al., 2015, p. 25). The idea that teachers achieve agency (and do not already have it) in order to act in a certain way enables us to position teacher knowledge as a phenomenon that emerges in two ways: as something that emerges in a given situation based on the capacity to take decisions and act in a given educational context and as produced knowledge that needs to be systematised and transferred.

4. THE EMERGENCE OF TEACHER EDUCATIONAL KNOWLEDGE

As we have already seen, reflecting on practice is a vital activity for the teaching profession (Domingo, 2020; Medina & Pérez, 2017). Nonetheless, when we add observation, collegiality, systematisation, and transference to this action, we find ourselves with a much broader and more complex phenomenon: the construction of educational knowledge (Malpica, 2013; Úbeda, 2018; Verástegui, 2019).

When speaking of teacher educational knowledge, we refer to the set of statements about the validity of educational practices based on systematised observation – searching for evidence – and the discussion of results on the basis of criteria. This set of statements is also part of a process of discussion between teachers and of transfer beyond the context of execution of practice. This is why teaching agency is, at the same time, a condition of possibility for educational knowledge and its source (Helms & Stokes, 2013; Shulman, 1987).

When defining the construct, as we find it in the literature, teacher educational knowledge is understood in two different ways that often seem not to be connected (Biesta et al., 2017). On the one hand, there’s the form that comprises this concept as the body of knowledge that makes the professionals as a group into “good teachers” (formal knowledge), which is usually prescribed by agents outside the profession. And on the other, the form that approaches the concept from the focus of the knowledge that teachers are capable of creating based on their educational practice (practical knowledge) (Fernández, 2014), that enables them to improve teaching–learning processes (Poulou et al., 2019).

Both dimensions of knowledge form part of teacher agency and, therefore, complement one another. However, the existing models relating to this question do not include both and certainly do not link the question of teacher knowledge to professional agency (Biesta et al., 2017). Furthermore, practical knowledge has often been to the detriment of formal knowledge (Moya & Luengo, 2019), something that is apparent in research, which has on the whole considered what knowledge teachers have and how it is executed in practice and has paid much less attention to how teachers produce knowledge that is projected both inside and outside the profession (Medina, 2006).

Within this last type, literature on action-research has studied this concept of teacher knowledge the most. However, although teachers cannot always join in with these processes of research, they continue to generate educational knowledge that is of value (Kemmis, 2006; Reis-Jorge et al., 2020) and which it is therefore necessary to take into consideration (Poulou et al., 2019). On the other hand, the other authors who investigate the question of teacher educational knowledge from this empowering focus (Schön, 1984; Villar Angulo, 1995) do not capture a complete vision of the construction of knowledge. In other words, an ecological and systemic vision of the phenomenon that requires interaction between the different elements and dimensions that comprise it and, therefore, of community processes – inside and outside the school – both in their generation and in their transfer (Moya & Luengo, 2019).

It is in this sense that the model we provide in this article sets out to resolve this question, incorporating teacher knowledge into the agency model from a dynamic and transversal focus, which makes it possible to approach the phenomenon from a systematic perspective that includes, on the one hand, the knowledge teachers possess and that which they produce and transfer and, on the other hand, the relationships between them. In this way, we achieve a working model for research, that makes it possible to explore the phenomenon of teacher educational knowledge and teacher agency, while taking into account the relationship between them.

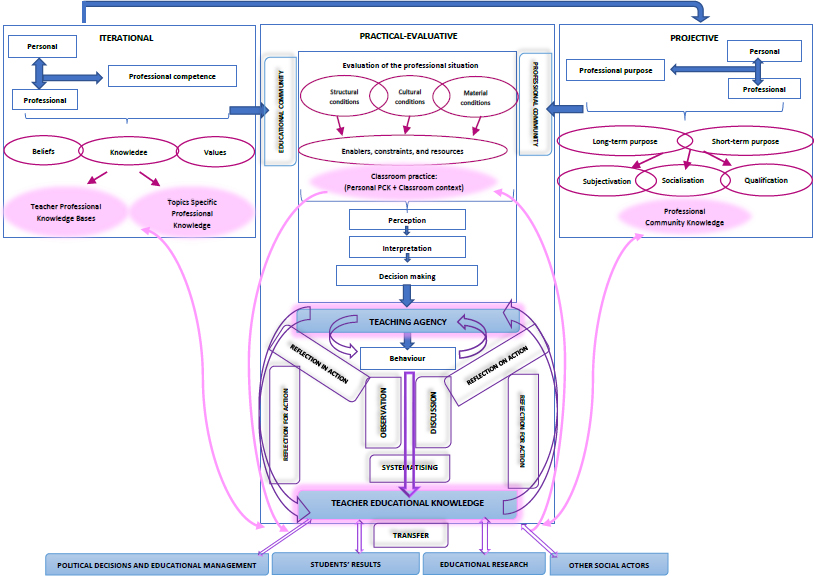

To do so, we start from the model of agency of Priestly et al. (2015) with its three constituent dimensions: iterational, practical-evaluative and projective. Furthermore, we have taken into account the expansion of the model of agency by Leijen et al. (2020), as these authors consider in greater depth the elements of each dimension and also incorporate reflection as a necessary process for achieving the agency that allows teachers to create knowledge in their practice.

Moreover, with the objective of integrating the phenomenon of teacher educational knowledge with the agency model, we have incorporated the various types of knowledge that teachers possess into the model agreed on during the PCK Summit in 2013 (Helms & Stokes, 2013). So, in our model we include teachers’ basic knowledge and their subject-specific professional knowledge in the iterational dimension, and their knowledge of classroom practice in the practical-evaluative dimension. We have also added several other elements: (i) interactions between the types of knowledge mentioned above; (ii) knowledge produced by the teacher; (iii) collective and professional elements that have an influence on teaching agency and on the production of this contextual knowledge (educational community and professional community); and (iv) a new category in the projective dimension that we have called knowledge of the professional community, which makes it possible to institutionalise and spread the knowledge produced by teachers (Moya & Luengo, 2019).

Furthermore, we have kept the proposal from the PCK model in which students’ results are a fundamental element of teachers’ educational knowledge. However, we include it not only as an influential part of the process of teacher knowledge production but also as a part that benefits from it. In this sense, we also note other agents that affect the process of knowledge transfer: political decisions and administration, research, and other educational agents.

Finally, the most significant contribution of this model is the link between the concept of agency and the concept of teacher educational knowledge. This connection is established on the basis of the professional dynamics we set out at the start of this article: reflection, observation, discussion, and systematisation. In the case of reflection, we have distinguished three levels depending on the moment in which it takes place: reflection in action, reflection on action, and reflection for action (Killion & Todnem, 1991; Schön, 1984).

FIGURE 1

SYSTEMIC MODEL OF TEACHER EDUCATIONAL KNOWLEDGe

Source: Based on the model of agency of Priestly et al. (2015), the expanded version of Leijen et al. (2020) and the model from the PCK Summit (Helms & Stokes, 2013)

As Figure 1 shows, reflection is understood to be a form of knowledge that guides action (Schön, 1984) and also as the thing that favours the setting out of knowledge that derives from training and experience (Leijen et al., 2020). In the same way, observation, discussion, and the systematisation of educational practice are carried out by the teacher when the objective is to produce educational knowledge. Educational knowledge, which is influenced by the three dimensions of agency but also shapes them, as in the case of the iterational and projective dimensions. In the case of the practical-evaluative dimension, the interaction is more recursive; given that teachers decide and act in a given context, they are capable of creating educational knowledge, which in turn broadens and advances the knowledge they possess regarding classroom practice and so enhances their achievement of agency.

Finally, the model presents how teachers can share their knowledge with the rest of the educational community and, in turn, how this community directly influences the knowledge that teachers produce and that, as we have explained, is incorporated into the different dimensions that comprise agency.

5. DISCUSSION AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Teacher educational knowledge has been and continues to be an important area of study in educational research (Fernández, 2014). However, most of the research carried out presents a partial and incomplete vision of this question (Medina, 2006). On the one hand, there is research that shows the educational knowledge that teachers incorporate in order to be a good professional, normally obtained, from the formative field and from research; and on the other hand, there is work that approaches research from the knowledge that the teacher is capable of constructing (Biesta et al., 2017). Furthermore, in this second type, there are few references that incorporate both the internal and outward-looking dimensions of the construction of teacher knowledge (Fernández, 2014; Medina, 2006). This is why we say that this line of research is incomplete.

Similarly, in the accepted models of teacher educational knowledge, two limitations are apparent. The first is that most of the models are not operational and, therefore, do not make it possible to examine the situation studied. Secondly, the operative models do not contain a complete vision of the knowledge, one that integrates both the dimensions of the knowledge obtained and the dimension of the knowledge constructed by teachers (Fernández, 2014). And, to a much lesser extent, we find models that incorporate both facets of the construction of teacher knowledge, the one that has an internal effect and the one that has an effect outside the profession.

On the other hand, if we want to study the question of teacher educational knowledge at an operational level, it is essential to start from a praxis focus that allows us to comprehend clearly what professional practice comprises, in other words, what knowledge it requires, how this knowledge is executed, and what knowledge is produced on the basis of it (Leijen et al., 2020). For this reason, we started in our proposal with a model of agency as a fundamental element in our research into teacher educational knowledge.

After reviewing the models that have been developed around educational knowledge and teacher agency, we selected the ones that offer an operative framework for inquiry: the PCK Summit model (Helms & Stokes, 2013) and the agency model of Priestley et al. (2015) in the version of it expanded by Leitjen et al. (2020). The former provides an agreed framework for the educational knowledge that teachers possess and are capable of building from within the profession. The latter provides a working model of what teacher agency is and how it is achieved.

The model we present in this article is intended to build on existing research into teacher agency and educational knowledge. In particular, the proposal we make integrates the production of educational knowledge as an element that completes and improves on the models selected and explained above. Specifically, the main contribution of our model is to locate teachers’ educational knowledge as a dynamic and transversal dimension of agency.

To this end we first included the model of the PCK Summit (Helms & Stokes, 2013) in the agency model of Priestley et al. (2015). We then expanded the model by incorporating the interactions between the knowledge teachers possess and produce and the dimensions of agency. And, in addition, a category of knowledge production (knowledge of the professional community) that corresponds with the projective dimension of agency and relates to the capacity of teachers as a group to institutionalise and transfer their knowledge (Malpica, 2013; Moya & Luengo, 2019).

Finally, to explain the relationship between the concepts of agency and teacher educational knowledge, we included collaborative professional dynamics: reflection, observation, discussion, and systematisation. In other words, the procedures that allow teachers, on the basis of their agency, to construct educational knowledge that derives from their educational practice (Domingo, 2020; Priestley & Drew, 2019; Verástegui, 2019). A knowledge that is systematic and can be transferred both within the profession and also outside it (Úbeda, 2018).

Our approach with this model is first to observe whether it provides us with an operational framework for examining the educational knowledge that teachers are capable of producing in collaborative practices. As it is a theoretical proposal, we must await its practical application to obtain more information about its functionality and so be able to discuss its theoretical contribution with clarity. However, we believe that this model could have the capacity to situate the classical inherited separation of theory and praxis in a space that is more productive and actually goes beyond this separation (Biesta, 2007; Domingo, 2020). We consider this possibility because the model we propose situates “theory” in education as one of the dimensions of teaching praxis given that teachers, in their agency, relate to knowledge as a set of tools (potential rules and customs) that can be used to react to given educational situations and which demonstrate their value in their capacity that potentially relates to a professional community and not just as a set of descriptive statements about educational phenomena that prove their value in relation to a methodology shared by a research community (Biesta, 2007; Groundwater-Smith et al., 2016; Willinghan & Daniel, 2021). Despite this consideration, it seems to us that such a debate falls outside the scope of this article and so we suggest that it would be an interesting line of research to pursue in future.

Similarly, we believe that another possible line of research would be to study the procedure for transferring teacher educational knowledge outside the profession (Groundwater-Smith et al., 2016). Although it goes beyond the scope of this article, we believe that it is fundamental to set out, as it appears in the model, the need for teacher knowledge to be made systematic and transferred to introduce it in the area of knowledge known as evidence-based education (Biesta, 2007; Reis-Jorge et al., 2020). We believe that without a clear intention to make teaching knowledge part of educational knowledge, it will be very difficult to achieve the desired educational improvement (Biesta et al., 2019; Malpica, 2013). Educational research, as well as political agents and other agents in society, must take into account and take seriously the evidence that comes from classroom practice and forms part of the knowledge of the professional community of teachers (Biesta, 2007; Groundwater-Smith et al., 2016). Similarly, educators must commit to the active role that corresponds to them in this field and seek to strengthen it as a fundamental part of their professional practice (Reis-Jorge et al., 2020; Rupérez, 2014).

Finally, a direct consequence of accepting this focus on the teacher educational knowledge and, consequently, of committing to the evidence coming from the classroom, is to back decisively the orientation of educational management and organisation in a way that facilitates the necessary professional dynamics for the construction and transfer of this knowledge (Malpica, 2013; Medina, 2006; Moya & Luengo, 2019). And also so that the spaces and structures necessary for educational evidence are created from constant feedback between research and classroom practice (Biesta et al., 2019) and, therefore, a solid and sustainable educational system can be built guided by the best available educational evidence (Biesta, 2007; Willinghan & Daniel, 2021).

REFERENCES

Biesta, G. (2007). Why “What works” won't work: evidence-based practice and the democratic deficit in educational research. Educational Theory, 57(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2006.00241.x

Biesta, G., Filippakou, O., Wainwright, E., & Aldridge, D. (2019). Why educational research should not just solve problems, but should cause them as well. British Educational Research Journal, 45(1), pp 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3509

Biesta, G., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2017). Talking about education: exploring the significance of teachers’ talk for teacher agency. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 49(1), 38-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2016.1205143

Burgess, S., Shenila, R., & Taylor, E. (2019). Teacher peer observation and student test scores: Evidence from a field experiment in English secondary schools. EdWorkingPaper, 19-139. Annenberg Institute at Brown University. https://www.edworkingpapers.com/ai19-139

Contreras, J., y Pérez de Lara, N. (2010). La experiencia y la investigación educativa. En J. Contreras y N. Pérez de Lara (Coords.), Investigar la experiencia educativa (pp. 21-86). Morata.

Croll, P. (1995). La observación sistemática en el aula. Muralla.

Dewey, J. (1933). How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process. Prometheus Books.

Domingo, A. (2020). Profesorado reflexivo e investigador. Propuestas y experiencias formativas. Narcea.

Fernández, C. (2014). Knowledge base for teaching and pedagogical content knowledge (PCK): some useful models and implications for teacher’s training. Problems of Education in the 21st century, 60, 79-100. https://www.scientiasocialis.lt/pec/node/files/pdf/vol60/79-100.Fernandez_Vol.60.pdf

Firestone, W. & Donaldson, M. (2019). Teacher evaluation as data use: what recent research suggests. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 31, 289-314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-019-09300-z

González, A. (1997). Estructuras de la praxis. Ensayo de una filosofía primera. Fundación Xavier Zubiri.

Groundwater-Smith, S., Mitchell, J., & Mockler, N. (2016). Praxis and the language of improvement: inquiry-based approaches to authentic improvement in Australasian schools. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 27(1), 80-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.975137

Helms, J., & Stokes, L. (2013). A meeting of minds around Pedagogical Content Knowledge: designing an international PCK summit for professional, community and field development. Inverness Research - PCK Summit Report. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286265312

Kemmis, S. (2006). Participatory action research and the public sphere. Educational Action Research, 14(4), 459-476. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790600975593

Killion, J., & Todnem, G. (1991). A process for personal theory building. Educational Leadership, 48(6), 14-16. https://www.ascd.org/ASCD/pdf/journals/ed_lead/el_199103_killion.pdf

Leijen, A., Pedaste, M., & Lepp, L. (2020). Teacher agency following the ecological model: how it is achieved and how it could be strengthened by different types of reflection. British Journal of Educational Studies, 68(3), 295-310. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2019.1672855

Malpica, F. (2013). Calidad de la práctica educativa. Referentes, indicadores y condiciones para mejorar la enseñanza-aprendizaje (4.ª ed). Graó.

Medina, J. L. (2006). La profesión docente y la construcción del conocimiento profesional. Lumen.

Medina, J. L., y Pérez, M. J. (2017). La construcción del conocimiento en el proceso de aprender a ser profesor: la visión de los protagonistas. Revista de currículum y formación del profesorado, 21(1), 17-38. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/567/56750681002.pdf

Moreno, J. M. (2018). Profesorado: más que una profesión. Cuadernos de pedagogía. Especial profesión docente, 489, 12-17.

Moya, J., y Luengo, F. (2019). Capacidad profesional docente. Buscando la escuela de nuestro tiempo. Anaya.

Murillo, J., Perines, H., y Lomba, L. (2017). La comunicación de la investigación educativa. Una aproximación a la relación entre la investigación, su difusión y la práctica docente. Revista de currículum y formación del profesorado, 21(3), 183-200. https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/profesorado/article/view/59794

Perines, H. (2018). ¿Por qué la investigación educativa no impacta en la práctica docente? Estudios sobre educación, 34, 9-27. https://doi.org/10.15581/004.34.9-27

Poulou, M., Reddy, L., & Dudek, C. (2019). Relation of teacher self-efficacy and classroom practices: a preliminary investigation. School Psychology International, 40(1), 25-48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034318798045

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher Agency. An ecological Approach. Bloomsbury.

Priestley, M., & Drew, V. (2019). Professional Enquiry: an ecological approach to developing teacher agency. In D. Godfrey & C. Brown (Eds.), An eco-system for research-engaged schools. Reforming education through research (pp. 154-170). Routledge. https://hdl.handle.net/1893/28253

Reis-Jorge, J., Ferreira, M., y Olcina-Sempere, G. (2020). La figura del profesorado-investigador en la reconstrucción de la profesionalidad docente en un mundo en transformación. Revista Educación, 44(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.15517/revedu.v44i1.39044

Roth, K., Wilson. C., Taylor, J. Stuhlsatz, M., & Hvidsten, C. (2019). Comparing the Effects of Analysis-of-Practice and Content-Based Professional Development on Teacher and Student Outcomes in Science. American Educational Research Journal, 56(4), 1217-1253. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831218814759

Rupérez, F. L. (2014). Fortalecer la profesión docente. Un desafío crucial. Narcea.

Schön, D. A. (1984). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books.

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

Spencer, D. (2014). Was moses peer observed? The ten commandments of peer observation of teaching. In J. Sachs & M. Parsell (Eds.), Peer review of learning and teaching in higher education. International Perspectives (pp. 183-200). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7639-5

Thoilliez, B. (2013). Implicaciones pedagógicas del pragmatismo filosófico americano. Una reconsideración de las aportaciones educativas de Charles S. Peirce, William James y John Dewey. Tesis doctoral. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. https://hdl.handle.net/10486/13475

Úbeda, J. (2018). Del cambio educativo a las mejoras educativas: el protagonismo del conocimiento educativo de los docentes. Cuadernos de pedagogía, 487(3), 76-81.

Verástegui, M. (2019). El conocimiento educativo de los docentes en la transformación y la mejora educativa. En H. Monarca, J. M. Gorostiaga, & Fco. J. Pericacho (Coords.), Calidad de la educación: aportes de la investigación y la práctica (pp. 171-192). Dykinson. https://hdl.handle.net/10486/686710

Villar Angulo, L. M. (Coord.). (1995). Un ciclo de enseñanza reflexiva. Estrategia para el diseño curricular. Ediciones Mensajero.

Viñao, A. (2018). La desprofesionalización de la docencia: viejas cuestiones, nuevas amenazas. Revista digital de educación del FEAE-Aragón, 23, 8-11. https://feae.eu/revista-forum-aragon-numero-23/

Willinghan, D., & Daniel, D. (2021). Making Education Research Relevant. How research can give teachers more choices. Education Next, 21(2). https://www.educationnext.org/making-education-research-relevant-how-researchers-can-give-teachers-more-choices/

Zeichner, K., & Liston, D. (1996). Reflective Teaching: An Introduction. Lawrence Erlbaurm

_______________________________

1. Research undertaken as part of the project “#Lobbyingteachers: theoretical foundations, political structures and social practices of public-private relations regarding teachers in Spain”. (Ref. PID2019-104566RA-I00). From the 2019 Call of the State R&D Programme.