ISSN: 0210-1696

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/scero.32214

ANALYZING CONTEXT TO IMPROVE OUTCOMES: RESEARCH AND BEST PRACTICES

Analizar el contexto para mejorar los resultados: investigación y buenas prácticas

Karrie A.Shogren

University of Kansas. EE. UU.

Recepción: 27 de agosto de 2024

Aceptación: 22 de octubre de 2024

Abstract: Context matters in the lives of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities and is acknowledged as an influencing factor in various approaches to understanding and developing systems of supports. However, there is not a shared and common understanding of context, how to operationalize it, and how to leverage contextual analysis to drive change in outcomes for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Researchers have engaged in work to operationally define context, recognize the multidimensionality of context, and define methods (i. e., contextual analysis) to assess contextual factors and drive systemic change. This paper provides an overview of this work, highlighting how a multidimensional understanding of context as multifactorial, multilevel, and interactive can recognize the totality of circumstances that comprise context. Using this understanding can drive contextual analysis and the implementation of a context-based change model to enhance personal outcomes. Ways contextual analysis can advance the adoption of a shared citizenship paradigm to advance personal and systemic outcomes is described.

Keywords: Context; personal outcomes; best practices.

Resumen: El contexto es importante en la vida de las personas con discapacidades intelectuales y del desarrollo y se reconoce como un factor influyente en diversos enfoques para comprender y desarrollar sistemas de apoyo. Sin embargo, no existe una comprensión compartida y común del contexto, cómo hacerlo operativo y cómo aprovechar el análisis contextual para impulsar cambios para las personas con discapacidades intelectuales y del desarrollo. Los investigadores han trabajado para definir operativamente el contexto, reconocer su multidimensionalidad y definir métodos (i. e., análisis contextual) para evaluar los factores contextuales e impulsar el cambio sistémico. Este artículo proporciona una visión general de este trabajo, destacando que una comprensión multidimensional del contexto como multifactorial, multinivel e interactivo puede identificar la totalidad de las circunstancias que lo componen. El uso de esta comprensión puede impulsar el análisis contextual y la implementación de un modelo de trabajo de campo basado en el contexto para mejorar los resultados personales. Se describen las formas en que el análisis contextual puede promover la adopción de un paradigma de ciudadanía compartida para promover resultados personales y sistémicos.

Palabras clave: Contexto; resultados personales; buenas prácticas.

1. Analyzing context to improve outcomes: Research and best practices

The term context is widely used in the intellectual and developmental disability field, and understanding context has been identified as key to supporting enhanced outcomes for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Context and its role in human functioning has been referenced in the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) Terminology and Classification Manuals since 2002 (Luckasson et al., 2002; Schalock et al., 2010; Schalock et al., 2021), and in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF; World Health Organization, 2001, 2007). The role that context plays in disability policy development, implementation, and evaluation has also been discussed around the globe (Buntinx, 2006; Schalock, 2017; Turnbull and Stowe, 2017; Verdugo et al., 2017) and the importance of understanding contextual factors in advancing disability and human rights are reflected in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, 2006).

While there is broad recognition that context matters in the lives of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, there has been a lack of a clear, operational definition of context in the field. For example, Shogren et al. (2014) identified, in a systematic literature search, over 117,000 articles published that referenced context and disability with 85,000 of these articles published in the 2000s. And the number has likely increased since this article was published. More recent analyses have suggested that while context remains commonly identified as a key factor in research, it is often used narrowly to refer to the investigation of a specific aspect of context, rather than recognizing the multidimensional nature of context (Shogren et al., 2020). To address the lack of a common operational definition or framework for understanding context, over the past decade researchers have engaged in work to further operationalize context (Shogren et al., 2014), define methods (i. e., contextual analysis) to assess contextual factors (Shogren, Schalock et al., 2018) and drive systemic change (Shogren, Luckasson et al., 2018), and recognize the multidimensionality of context (Shogren et al., 2020).

The goal of this work has been to advance research and practice that enhances personal outcomes as well as advance systemic changes that challenge barriers and biases that limit opportunities for people with disabilities to access effective systems of supports aligned with a shared citizenship paradigm that focuses on the “engagement and full participation of people with IDD as equal, respected, valued, participating, and contributing members of every aspect of the society” (Schalock et al., 2022, p. 65). In the sections that follow, we described each of these areas of work, highlighting how they can advance research, policy, and practice in the intellectual and developmental disability field.

2. Operational definition

In early work (Shogren et al., 2014), we conducted a comprehensive review of the literature, concluding that there was not a consensus definition of context despite the widespread use of the term in lay, technical, and research publications. To address this need, we synthesized the literature and introduced a consensus definition of context:

Context is a concept that integrates the totality of circumstances that comprise the milieu of human life and human functioning. Context can be viewed as an independent and intervening variable. As an independent variable, context includes personal and environmental characteristics that are not usually manipulated such as age, language, culture and ethnicity, gender and family. As an intervening variable, context includes organizations, systems, and societal policies and practices that can be manipulated to enhance functioning. As an integrative concept, context provides a framework for: (a) describing and analyzing aspects of human functioning such as personal and environmental factors, supports planning, and policy development; and (b) delineating the factors that affect, both positively and negatively, human functioning (Shogren et al., 2014, p. 110).

As we have applied this definition, over time, we have identified six assumptions that are essential to the application of the definition.

1.Human functioning is influenced by context.

2.Context is multifactorial, multidimensional, and interactive.

3.Context is best understood from the perspective of the individual and his/her values, personal goals, and personal desires.

4.Context influences human functioning by acting as an independent variable or an intervening variable.

5.Context is observable and measurable.

6.Responsive contexts can be built that enhance personal outcomes (Shogren et al., 2021).

3. Multidimensional Model of Context

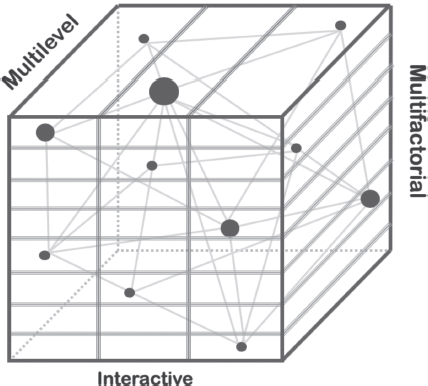

To reflect this definition and assumptions, it is necessary recognize the “totality of circumstances” that reflect context, moving away narrow applications. A multidimensional understanding of context (see Figure 1) provides a framing to comprehensively consider context as multifactorial, multilevel, and interactive (Shogren et al., 2020). Multifactorial refers to the array of personal and environmental factors that influence the lives of people across contexts. These factors both shape one’s personal culture and outcomes as well as reflect the overarching factors that can facilitate (e. g., adoption of the shared citizenship paradigm and social-ecological, strengths-based understandings of disability in policies, organizations, and practice) and hinder (e. g., structural racism and ableism reflected in policies and practices that limit access and opportunities) valued outcomes. Multilevel refers to the layers of influence within which contextual factors shape how people live, learn, work, and enjoy life. An ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) is used to define these layers and includes the: micro or the immediate social setting including the person, family, close friends, and advocates; meso that includes the neighborhood, community, and any organizations providing supports; and macro that includes the larger policy context and supports delivery system, and the overarching pattern of culture, society, country, or sociopolitical influences. Finally, context is interactive as factors operate across the layers of influence, creating a complex web of influence amplifying various levels and factors for each person. Recognition of this interactivity necessitates efforts to build systems of supports that recognize that addressing only one contextual level or factor will not authentically address the totality of experiences that define each person’s context, their cultural and social identities, and needed systems of supports.

Figure 1. A Multidimensional Conceptual Model of Context

Source: Shogren et al., 2020.

Conceptualizing context as a multidimensional phenomenon and understanding its multilevel, multifactorial, and interactive properties advances a comprehensive framework that can be used to guide contextual analysis which seeks to recognize the multiple levels and factors that shape a person’s life and outcomes over time to enhance personal and societal outcomes. Only by understanding and targeting these complex interactions can the potential of context and contextual analysis be used to make change at the individual, family, organization, community and system level. Further, when such change occurs within the context of the shared citizenship paradigm (Luckasson et al., 2023; Schalock et al., 2022), reframing of systems of supports can occur to enhance outcomes that advance self-determination, full citizenship, lifelong learning, productivity, wellbeing, inclusion in society and community life, and human relationships.

4. Contextual analysis

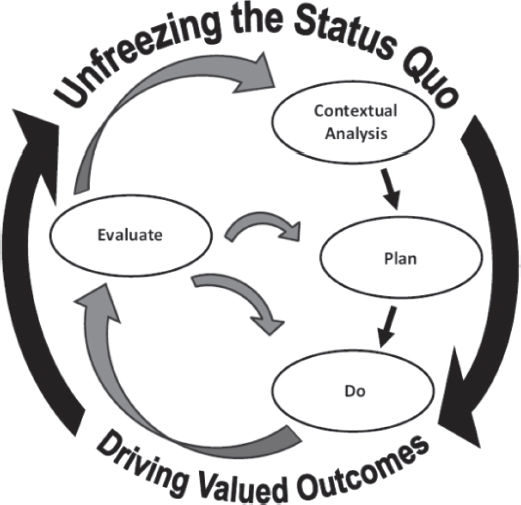

Based on a multidimensional understanding of context, a context-based change model can be adopted across ecological levels to unfreeze the status quo and drive valued outcomes at the individual, family, community, organization, and societal level (Shogren, Schalock et al., 2018). We have identified five key steps involved in conducting a contextual analysis to enable context-based change. These five steps included identifying (1) the contextual factors that hinder change, (2) the discrepancies between where one is and where one wants to be, (3) the forces for change that will increase momentum and receptivity, (4) ways to promote adoption and application, and (5) ways to increase stakeholder participation in making change (Shogren, Schalock et al., 2018).

Further, we are increasingly recognizing that contextual analysis can be applied at the individual or micro level to enhance personal outcomes, as well as at the meso and macro level to bring about change through unfreezing the status quo and enhancing personal outcomes through systemic change (Shogren, Schalock et al., 2018). We have specifically described how contextual analysis can be used by systems to address their responsibility to build contexts that increase responsiveness to contextual factors and leverage the power of contextual analysis to enhance personal outcomes through community, organization and system practices (Shogren, Luckasson et al., 2018). This responsibility entails both being responsive to how people with a disability and their families perceive the contextual factors that impact their lives and implementing change strategies based on contextual analysis and a context-based change model such as that shown in Figure 2 (Shogren, Schalock et al., 2018). In doing so, organizations and systems can be more effective in leveraging the power of context.

Figure 2. A Context-Based Change Model

Source: Shogren, Schalock et al., 2018.

Thus, in conducting a contextual analysis organizations and systems can seek to “plan, do, and evaluate” as shown in Figure 2. Table 1 provides additional details on each of these steps and how they can be applied to advance outcomes aligned with a multidimensional perspective of context. To advance contextual analysis aligned with a shared citizenship paradigm to advance meaningful personal and systemic outcomes, we recommend (Shogren et al., 2021):

1.Identify the multidimensional properties of context. As discussed in reference to the multidimensional model of context presented in Figure 1, context is multilevel, multi-factorial, and interactive. These properties inform the multiple applications of context and highlight the interactive impact of context-based change strategies.

2.Use contextual analysis as the analytic or measurement method to study and understand context. As described in Table 1, contextual analysis can be used for a number of knowledge-generating purposes. Chief among these are: (a) identify contextual factors that hinder change and forces that facilitate change at the individual or organization/ systems level; (b) identify personal outcome indicators; (c) identify contextual factors that influence valued outcomes across ecological systems; (d) identify interactions between ecological systems and contextual factors; and (e) assess a system’s responsiveness to building contexts that enhance personal outcomes.

3.Implement a context-based change process. The model presented in Figure 2 and explained in Table 1 identify the key process steps involved in unfreezing the status quo and driving valued outcomes. Important action steps associated with the analysis, plan, do, and evaluate components of the change process are identified in Table 1.

4.Incorporate a multilevel and multipurpose approach to evaluation. In reference to a multilevel approach, policy evaluation can focus on the status of personal outcomes and/or the organization or system’s responsiveness to build contexts that benefit individuals and society and are aligned with a shared citizenship paradigm.

Table 1. Context-based change model components, examples, and sources for more information

Model Component |

Description |

Examples of Information Obtained from a Contextual Analysis or Action Steps Related to Planning, Doing, and Evaluating |

Source for Further Explanation of the Model Components |

Contextual Analysis |

Use contextual analysis to identify: 1.Contextual factors that hinder change and forces that facilitate change 2.Contextual factors/supports that influence personal outcomes 3.Contextual factors that influence valued outcomes across ecological systems 4.Interactions between ecological systems and contextual factors |

•Inflexible mind set •Defect model of disability •Process not outcome evaluation •Person-centered planning •Personalized support strategies •Inclusive environments •Public policies and practices based on human capacity, equity, inclusion, empowerment, and self-determination •Provision of community living supports and residential status •Provision of supported employment programs and work/employment status |

Shogren, K. A. et al. (2018). The use of a context-based change model to unfreeze the status quo and drive change to enhance personal outcomes of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 15, 101-109. •Figure 1 provides more information about contextual analysis and the context-based change model •Tables 1 and 2 summarize the potential results of contextual analyses involving individuals (Table 1) and organizations/systems (Table 2) |

Plan |

A disciplined, detailed, forward-focused activity that integrates the results of one or more contextual analyses and targets context-based influencing factors |

•Identify the current interactions in the life of the person •Prioritize desired personal goals •Address factors that hinder change •Address forces that drive change •Integrate factors that facilitate change •Identify systems of supports elements that enhance personal outcomes |

Shogren, K. A. et al. (2018). The use of a context-based change model to unfreeze the status quo and drive change to enhance personal outcomes of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 15, 101-109. •Text related to “planning” |

Do |

Operationalizes the “plan component” by implementing specific change strategies that are based on information obtained from the contextual analysis and that incorporate activities identified in the planning process |

•Procure and coordinate planned systems of supports elements across ecological systems levels •Develop a personal support plan that aligns personal goals and support needs to specific systems of supports elements •Use strategic execution that involves team-developed user-friendly support plans |

Shogren, K. A. et al. (2018). The use of a context-based change model to unfreeze the status quo and drive change to enhance personal outcomes of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 15, 101-109. •Text related to “doing” Shogren, K. A. et al. (in press). Using a multi-dimensional model to analyze context and enhance personal outcomes. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. •Text regarding “applying the context-based enhancement cycle” |

Evaluate |

Evaluate the status of personal outcomes; and/or an organization or system’s responsiveness to context |

Exemplary personal outcome indicators: •Self-determination: makes choices, participates in decision making •Full citizenship: respect, privacy, freedom from exploitation, and freedom of expression •Education/life-long learning: personal growth and development, ongoing education •Productivity: work/employment status, meaningful engagement in activities •Well-being: health status, emotional status, physical status, personal safety •Inclusion in society and community life: community involvement, social inclusion •Human relations: social network, friendships, meaningful relations Exemplary system responsiveness indicators: •Thoroughness of the contextual analysis •Alignment of support strategies •Characteristics of the support strategies planned and implemented |

Shogren, K. A et al. (2018). The responsibility to build contexts that enhance human functioning and promote valued outcomes for people with intellectual disability: Strengthening system responsiveness. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 56, 287-300. •Appendix A provides an evaluation framework to assess the quality of a system’s responsiveness to context •Text regarding “assessing the quality of a system’s responsiveness (pp. 289-291) Shogren, K. A. et al. (in press). Using a multi-dimensional model to analyze context and enhance personal outcomes. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. •Table 4 discusses the alignment of contextual factors, and personal outcome indicators •Table 1 provides specific indicators to assess a system’s response to building contexts that enhance personal outcomes for specific indicators |

Note. From Shogren et al. (2021).

5. Conclusion

Transformations in the field of intellectual and developmental disabilities are advancing a shared vision for actualizing the shared citizenship paradigm through supporting the full engagement and participation of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities in all aspects of society (Schalock et al., 2022). To enhance the adoption and integration of the shared citizenship paradigm, understanding context is essential and can be used to guide contextual analysis that: (a) determines the broad contextual factors that hinder change and the forces for change that will increase momentum and receptivity for change; (b) ways to promote adoption and application, particularly of systemic changes; and (c) ways to increase lived experience expertise in making change (Shogren, Schalock et al., 2018). Unfreezing the status quo across contexts and advancing systemic changes are necessary to enhance personal outcomes and advance shared citizenship leading to enhanced personal outcomes.

6. Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all the people with disabilities and partners across the globe that have participated in this work. She would also like to acknowledge the partnership of Ruth Luckasson and Bob Schalock in all of the ideas shared in this manuscript and to thank the entire Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities team who supported this work and made this manuscript possible. Finally, the author would like to thank the leaders of the XII International Scientific Conference on Research on People with Disabilities for their work to advance enhanced outcomes for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities across the globe.

7. Bibliographical references

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Buntinx, W. H. E. (2006). The relationship between the WHO-ICF (International Classification of Functioning, Disaiblity and Health) and the AAMR 2002 system. In H. Switzky and S. Greenspan (Eds.), What is mental retardation? (pp. 6-10). American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Luckasson, R., Borthwick-Duffy, S., Buntinx, W. H. E., Coulter, D. L., Craig, E. P. M., Reeve, A., Schalock, R. L., Snell, M. E., Spitalnik, D. M., Spreat, S. and Tasse, M. J. (2002). Mental retardation: Definition, classification, and systems of support (10th ed.). American Association on Mental Retardation.

Luckasson, R., Schalock, R. L., Tassé, M. J. and Shogren, K. A. (2023). The intellectual and developmental disability shared citizenship paradigm: its cross-cultural status, implementation and confirmation. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 67(1), 64-76. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12992

Schalock, R. L. (2017). Introduction to the special issue on disability policy in a time of change. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 55(4), 215-222. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-55.4.215

Schalock, R. L., Borthwick-Duffy, S., Bradley, V., Buntix, W. H. E., Coulter, D. L., Craig, E. P. M., Gomez, S. C., Lachapelle, Y., Luckasson, R. A., Reeve, A., Shogren, K. A., Snell, M. E., Spreat, S., Tasse, M. J., Thompson, J. R., Verdugo, M. Á., Wehmeyer, M. L. and Yeager, M. H. (2010). Intellectual disability: Definition, classification and systems of support (11th ed.). American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Schalock, R. L., Luckasson, R. and Tassé, M. J. (2021). Intellectual disability: Definition, diagnosis, classification, and systems of supports (12th ed.). American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Schalock, R. L., Luckasson, R., Tassé, M. J. and Shogren, K. A. (2022). The IDD paradigm of shared citizenship: Its operationalization, application, evaluation, and shaping for the future. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 60(5), 426-443. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-60.5.426

Shogren, K. A., Luckasson, R. and Schalock, R. L. (2014). The definition of context and its application in the field of intellectual disability. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 11(2), 109-116. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12077

Shogren, K. A., Luckasson, R. and Schalock, R. L. (2018). The responsibility to build contexts that enhance human functioning and promote valued outcomes for people with intellectual disability: Strengthening system responsiveness. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 56(4), 287-300. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-56.5.287

Shogren, K. A., Luckasson, R. and Schalock, R. L. (2020). Using a multi-dimensional model to analyze context and enhance personal outcomes. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 58(2), 95-110. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-58.2.95

Shogren, K. A., Luckasson, R. and Schalock, R. L. (2021). Leveraging the power of context in disability policy development, implementation, and evaluation: Multiple applications to enhance personal outcomes. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 31(4), 230-243. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207320923656

Shogren, K. A., Schalock, R. L. and Luckasson, R. (2018). The use of a context-based change model to unfreeze the status quo and drive valued outcomes. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 15(2), 101-109. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12233

Turnbull, H. R. and Stowe, M. J. (2017). A model for analyzing disability policy. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 55(4), 223-233. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-55.4.223

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability. https://www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?navid=14&pid=150

Verdugo, M. Á., Jenaro, C., Calvo, I. and Navas, P. (2017). Disability policy implementation from a cross-cultural perspective. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 55(4), 234-246. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-55.4.234

World Health Organization. (2001). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.

World Health Organization. (2007). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Children and youth version.