Education in the Knowledge Society 22 (2021)

Influence of COVID on the Educational Use of Social Media by Students of Teaching Degrees

Influencia del COVID en el uso educativo de las Redes Sociales en estudiantes de Grados de Maestro

Raquel Gil-Fernándeza, Alicia León-Gómezb, Diego Calderón-Garridoc

aUniversidad Internacional de La Rioja, Logroño, España.

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9881-8641raquel.gilfernandez@unir.net.

bUniversidad Internacional de La Rioja, Logroño, España.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4519-8175alicia.leon@unir.net

cSerra Húnter Fellow, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, España

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2860-6747dcalderon@ub.edu

ABSTRACT

The situation caused by SARS-CoV-2 has resulted in the intensive use of technology in all fields, including education and interactions between students. This research seeks to identify changes in the way social media have been used for educational purposes by students of teaching degrees both before and after lockdown. Based on an online survey administered to a sample of 524 students from different Spanish universities in which it has been observed how their use has generally been very similar, although significant differences have been detected according to the kind of university. In this capacity, the use of social media for academic purposes has increased in universities offering traditional classroom-based courses, while it has remained the same in virtual universities which, due to their particular idiosyncrasies, have not been directly affected.

Keywords:

Social media

Higher education

COVID

Teachers Degrees

RESUMEN

La situación originada por el SARS-CoV-2 ha desembocado en un uso intensivo de la tecnología en todos los ámbitos, incluido el educativo y la relación entre el alumnado. En esta investigación se ha planteado comprobar cómo ha cambiado el uso educativo pre y post confinamiento de las redes sociales entre los estudiantes de grado de maestro. A través de una encuesta online dirigida a una muestra de 524 estudiantes de diferentes universidades españolas en las que se ha observado cómo el uso, de forma genérica, ha sido muy parecido, pero encontrándose grandes diferencias en función de la tipología de universidad. En este sentido, se ha constatado cómo el uso de las redes sociales con fines académicos ha crecido en las universidades tradicionalmente presenciales y se ha mantenido en las universidades virtuales que por su propia idiosincrasia no se han visto afectadas de forma directa.

Palabras clave:

Redes sociales

Enseñanza superior

COVID

Grado de Maestros

1. Introduction

The health crisis caused by the breakout of SARS-CoV-2 has triggered not only anxiety and a sense of unease in our daily lives, but also a number of reactions, changes and challenges in all aspects of life, including education. The impact has been such that 85% of students, in a total of 180 countries, have stopped attending their centre of education (Rogers & Sabarwal, 2020). This situation has resulted in the intensive use of technology which, as noted by Chamarro (2020), will change perceptions of ICT in general, and of social media in particular. This is due to the fact that they are used not only in the labour market, but also in social and family environments, as “social media are simply a means of expressing ourselves and reflecting the type of person we are” (p. 9).

During their initial teacher training, teachers are part of the educational community which, following the initial shock, has had to adapt to new uses and circumstances, not least during the lockdown period. The effort that these individuals have been required to make is two-fold. Those studying classroom-based courses have had to redefine their role as students and adapt, all of a sudden, to completely virtual courses, being custodians of the successes and failures of institutions, their resources and the praxis of the teachers themselves. All students - either studying classroom-based or online courses - have had to reflect on their digital teaching skills with a view to their future, their own shortcomings and those of the educational system in the light of the new scenario, as those who study online courses may perform well in their current role as "virtual" students, but endure the same concerns and insecurities in their role as future teachers.

This study is therefore a continuation of a line of research already underway, to expand on certain uses and customs and verify the change that they have experienced in the periods of total lockdown. The aim is to add it to all other studies being produced during the emergency facing the educational system and to constitute a new and necessary line of research which is still in development. It is based on the fact that the comparison of a specific aspect between both methodologies, classroom-based and virtual, in this case, must be subject to the obligatory nature and emergency in the former, and consider the brief period of the analysis and the undoubted impact on the individuals who have taken part in the study.

In keeping with the hypothesis of Hodges, Moore, Lockee, Trust and Bond (2020) in referring to the current reality of classroom-based higher education as emergency remote teaching to distinguish it from the previously established, instrumentalised and regulated forum of universities that were already operating online. As indicated in their work, the idea and aim of forging bona fide learning communities which develop a comfortable, autonomous and self-regulating working rhythm which focuses of critical thinking and autonomy, are diluted. This idea was conceived years before by authors such as Carneiro, Lefrere, Steffens and Underwood (2011) or Maraver, Hernando and Aguaded (2012), both via the media used in the midst of a contingency situation and via the scope of the aim. A scenario is therefore revealed at all educational levels, with fewer technological means than might have been expected and desirable and scant capacity to manage learning networks (Diez-Gutiérrez & Gajardo-Espinoza, 2020). Other authors, such as García-Peñalvo, Corell, Abella-García and Grande (2020), paint a brighter picture, on the understanding that although “It cannot be claimed that this urgent and unexpected action is analogous in experience, planning and development to the proposals that are specifically designed from conception to be delivered online” (p. 2), they also defend that, albeit faced by an emergency, universities offering classroom-based courses have made an acceptable transition to the online sphere and contribute best practice recommendations in terms of assessments. This divergence of opinion is due to the fact that every University, Faculty, and even Divisions or Departments within the same institution, have had different responses depending on their capacity to respond to instructional design, teaching staff whose digital skills are generally at an advanced level, resources and even classroom response.

On this basis, the objective of this research is to identify changes in the way social media have been used for educational purposes by students of teaching degrees both before and after lockdown, by detecting differences according to gender and type of university (classroom-based or online) and to conclude whether a response has been found to the same during the crisis.

2. Methodology

In order to achieve the proposed aims, an ad hoc questionnaire (available at https://reunir.unir.net/123456789/6695) was designed and validated in such a way that it would be possible to consider the specific characteristics of the students of teaching degrees relating to Early Education, Primary Education and Dual Early and Primary Educations, both before and during the lockdown period. The questionnaire was designed by a panel of six experts in Educational Technology, using the Delphi method (Somerville, 2008). In this process, a Cohen’s Kappa value of .85 was obtained.

The final questionnaire was distributed through the online formsite platform. In the case of non-confined students, they responded in November 2019 and February 2020. In the case of confined students, they did so in March, April and June 2020. The sample was accessed through its institutional emails. The participating students signed to provide their free, prior and informed consent implicit in the questionnaire itself, knowing that they could leave the study at any time they wished. The collection and subsequent analysis of the results were carried out using the quantitative analysis software Statistic Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 21.0. Besides descriptive statistics, statistical differences were detected based on Kruskal-Wallis tests and Levene’s statistic with a view to verifying homogeneity of variance. ATLAS.ti software, version 8.4.3, was used for qualitative analysis purposes.

After cleaning the data, the analysed sample was characterised by a total of 524 students: 184 during lockdown and 340 prior to this period. Table 1 features the sample according to gender, age and degree title.

Table 1. Description of the same according to gender, age and type of university. Source: Compiled by author.

No. of participants |

Male |

Female |

Age |

Early Education |

Primary |

Dual |

Classroom-based |

Virtual |

|

Before lockdown |

340 |

45 13.2% |

295 86.8% |

M= 27.06 SD = 8.34 |

126 (37.1%) |

198 (58.2%) |

16 (4.7%) |

175 (51.5%) |

165 (48.5%) |

Lockdown |

184 |

43 23.4% |

141 76.6% |

M= 24.16 SD = 7.45 |

7 (3.8%) |

177 (96.2%) |

8 (4.3%) |

65 (35.3%) |

119 (64.7%) |

Total |

524 |

88 (16.8%) |

436 (83.2%) |

M= 25.0 SD = 8.17 |

133 (25.4%) |

375 (71.6%) |

16 (3.1%) |

240 (45.8%) |

284 (54.2%) |

In respect of internal reliability, the questionnaire has identified a remarkable index (Cronbach's Alpha .869; .861 in the case of pre-lockdown and .873 in the case of lockdown).

3. Results

As shown by table 2, the most commonly used social media were WhatsApp (96.7%), Facebook (78.1%) and Instagram (76.4%). If we look at the variation between use before and during lockdown, statistical differences are detected in the case of Facebook (Z = -5.757; p < .001) which was used more frequently before lockdown (83.8%) than during this period (54.8%).

Table 2. Results obtained. Source: Compiled by author.

Habitually used |

Educational use |

|||||||||||

No |

Yes |

Never |

Sometimes |

Often |

Always |

|||||||

Before lockdown |

Lockdown |

Before lockdown |

Lockdown |

Before lockdown |

Lockdown |

Before lockdown |

Lockdown |

Before lockdown |

Lockdown |

Before lockdown |

Lockdown |

|

138 26.3% |

286 73.7% |

127 32.9% |

154 39.9% |

80 20.7% |

225 6.5% |

|||||||

55 16.2% |

83 45.1% |

285 83.8% |

101 54.9% |

96 33.7% |

31 30.7% |

108 37.9% |

46 45.5% |

59 20.7% |

21 20.8% |

22 7.7% |

3 3% |

|

121 23.1% |

403 76.9% |

173 42.9% |

126 31.3% |

60 14.9% |

44 10.9% |

|||||||

80 23.5% |

41 22.3% |

260 76.5% |

143 77.7% |

132 52.8% |

41 28.7% |

63 24.2% |

63 44.1% |

28 10.8% |

32 22.4% |

37 14.2% |

7 4.9% |

|

247 47.1% |

277 52.9% |

33 11.9% |

80 28.9% |

109 39.4% |

55 19.9% |

|||||||

139 40.9% |

108 58.7% |

201 59.1% |

76 41.3% |

25 12.4% |

8 10.5% |

66 32.8% |

14 18.4% |

75 37.3% |

34 44.7% |

35 17.4% |

20 26.3% |

|

Skype |

203 38.7% |

321 61.3% |

135 42.1% |

116 36.1% |

49 15.3% |

21 6.5% |

||||||

99 29.1% |

104 56.5% |

241 70.9% |

80 43.5% |

107 44.4% |

28 35% |

98 28.8% |

18 22.5% |

25 10.4% |

24 30% |

11 4.6% |

10 12.5% |

|

Sound Cloud |

474 90.5% |

50 9.5% |

17 34% |

22 44% |

9 18% |

2 4% |

||||||

304 89.4% |

170 92.4% |

36 10.6% |

14 7.6% |

13 36.1% |

4 28.6% |

15 41.7% |

7 50% |

6 16.7% |

3 21.4% |

2 5.6% |

0 |

|

Tumblr |

483 92.2% |

41 7.8% |

26 63.4% |

9 22% |

4 9.8% |

2 5.6% |

||||||

308 90.6% |

175 95.1% |

32 9.4% |

9 4.9% |

19 59.4% |

7 77.8% |

7 21.9% |

2 22.2% |

4 12.5% |

0 |

2 6.3% |

0 |

|

219 41.8% |

305 58.2% |

115 37.7% |

116 38% |

50 16.4% |

24 7.9% |

|||||||

138 40.6% |

81 44% |

202 59.4% |

103 56% |

67 33.2% |

48 46.6% |

76 37.6% |

40 38.8% |

41 20.3% |

9 8.7% |

18 8.9% |

6 5.8% |

|

Whats App |

18 3.4% |

506 96.6% |

72 14.2% |

156 30.8% |

184 36.4% |

94 18.6% |

||||||

10 2.9% |

8 4.3% |

330 97.1% |

176 95.7% |

36 10.9% |

36 20.5% |

106 32.1% |

50 30% |

127 38.5% |

57 32.4% |

61 18.5% |

33 18.8% |

|

Youtube |

85 16.2% |

439 83.8% |

24 5.5% |

135 30.8% |

218 49.7% |

62 14.1% |

||||||

41 12.1% |

44 23.9% |

299 87.9% |

140 76.1% |

18 6% |

6 4.3% |

92 36.8% |

43 30.7% |

149 49.8% |

69 49.3% |

40 13.4% |

22 15.7% |

|

Source: Compiled by author.

As for their use for educational purposes, the most commonly used social media, expressed as a percentage, were YouTube (x = 1.72; SD = .773), Pinterest (x = 1.64; SD = .927) and WhatsApp (x = 1.61; SD = .930). In this regard, and in respect of use before and during lockdown, Skype was characterised by statistical differences (Z = -3.521; p < .001) as it was used for educational purposes much more frequently during lockdown (x = 1.30; SD = .939) than before this period (x = .75; SD = .819).

In respect of differentiation according to the degree of study, statistical differences were only observed in the case of primary students who used Skype for educational purposes (z = -2.687; p = .004) more during lockdown (x = 1.29; SD = .946) than before this period (x = .83; SD = .861); Instagram (z = -2.131; p = .003), which was also used more during (x = 1.01; SD = .842) than before (x = .80; SD = 1.031); and Twitter (z = -2.315; p = .003) which was used more before (x = 1.03; SD = .989) than during (x = .74; SD = .859).

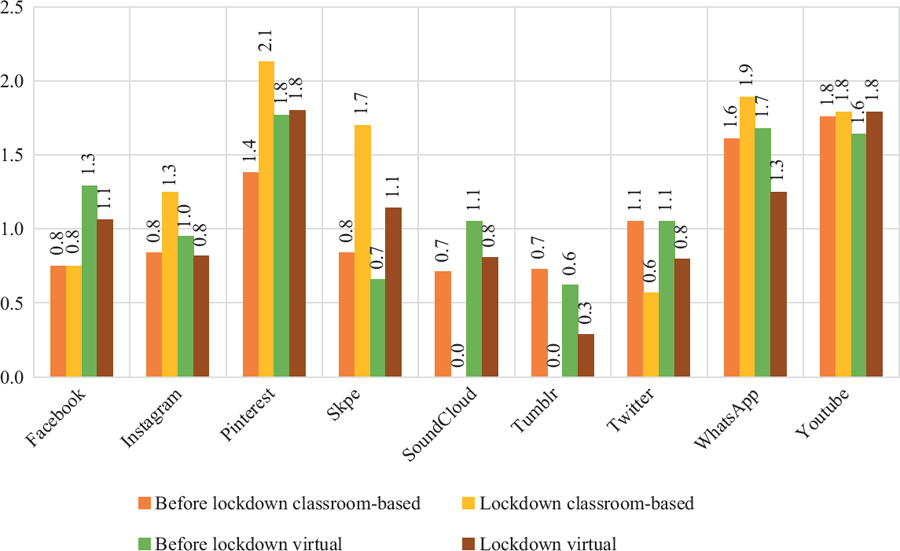

As for the type of university, as shown by Figure 1, disparate trends were generally observed in the use of social media for educational purposes.

Figure 1. Use of social media before and during lockdown according to type of university. Compiled by author.

In this regard, table 3 includes the statistical differences between the various media before and during lockdown, distinguished according to type of university.

Table 3. Statistical differences before and during lockdown according to type of university. Source: Compiled by author.

Skype |

Tumblr |

Youtube |

SoundCloud |

|||||||

Classroom-based |

Z P |

-,194 ,851 |

-2.732 ,004 |

-2.141 ,034 |

-3.149 ,002 |

-,817 ,429 |

-1.731 ,078 |

-1.485 ,245 |

-,072 ,931 |

|

Virtual |

Z p |

-1.051 ,292 |

-,258 ,761 |

-,275 ,751 |

-2.620 ,001 |

-,303 ,768 |

-1.385 ,187 |

-2.740 ,004 |

-,715 ,495 |

-,353 ,720 |

As for gender, statistical differences were only observed in the case of women in terms of the use of Skype for educational purposes (z = -3.379; p = .001), which was more frequent during lockdown (x = 1.29; SD = .913) than before this period (x = .73; SD = .808); and in the case of men, YouTube (z = -2.487; p = .003) was used more commonly during lockdown (x = 2.15; SD = .518) than before this period (x = 1.64; SD = .668).

In respect of the reasons for using social media for educational purposes, the established codes were the same both before and during lockdown; most answers were connected to keeping in touch with friends during lockdown via the media which allowed them to make video calls and synchronise the exchange of views. Thus, for instance, subject#18 remarked that “I use WhatsApp to contact classmates who share notes with me or who are involved in group tasks with me” or subject#19 who stated that “during quarantine, we're in video conferences all day long”, or subject#47 who noted that “I have often used Skype to talk discuss and share work with group members, because we have to take advantage of the media available to us, or subject#50 who pointed out that “I use Skype and WhatsApp to see my classmates and I think one of the advantages is that we can communicate very quickly”.

More broadly, the study identified a constant use to seek out educational experiences, as asserted by subject# 124 who stated that “Facebook, like YouTube, allows me to watch videos of numerous professionals from the field in question who share their experiences”. There was also evidence of pragmatism when it came to looking for inspiration for academic work through social media, as stated by subject # 72 in recognising that "I am looking for information about some academic themes, I read articles and I watch activities that I can use in my work”. A similar case was described by subject # 315 who used social media for the purpose "of keeping abreast of the latest educational news and also of being able to innovate and learn about other resources, because a teacher must always be on top of their subject and never stop learning" or directly of "looking for educational resources" (subject # 194).

Twitter tended to be used as a tool for reflection by teaching staff, as remarked by subject#410 who explained that “We have to use Twitter every day we have class to express our thoughts”, or subject#47 who stated that “I only use Twitter at present for one module, after each class we post a tweet, on the Twitter account that we have created for the working group, which we have worked on”.

Finally, there was a clear trend towards self-tuition, as in the case of subject#315 who stated that they used it “to study by myself. Especially YouTube when I need to find something out. A good tutorial is sometimes the best thing. Or groups of people who are available”.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

As shown by Table 2, before lockdown, students from the sample opted for a social, rather than a predominant educational use of Facebook (83.8%), which contrasted with the use of WhatsApp and YouTube, which have always maintained a balance between the educational and social function, Therefore, Facebook, WhatsApp and YouTube were used predominantly for social purposes while WhatsApp and YouTube, along with Skype and Instagram, were used predominantly for educational purposes. This situation remained unchanged, albeit with subtle differences, during lockdown.

Analysis of the data obtained reveals two substantial issues regarding the intensity of the use of social media, which remains almost stable for students of online universities, even falling slightly for all media, with the exception of Skype, while the use of some media increases for students of classroom-based universities, which is the case not only of Skype, whose use practically doubles, but also of Pinterest and WhatsApp. On the other hand, the educational use of these media has remained practically the same, in view of the responses to the open-ended question. According to the data of the sample, this was the case since, of the students questioned, those who were studying a classroom-based course doubled their use, while in the case of online students, it is the only medium whose use increases, in contrast with the sustained or lower level of use of others, thereby taking advantage of the synchrony between users.

Looking at the use of Skype, it is evident that it represents an example of a medium with usability and potential scope for optimisation in respect of any purpose which requires connectivity, including learning purposes, as it is a free, multi-platform and versatile medium. During lockdown, tools which provide temporary support and are easy to configure will habitually be used (Hodges, Moore, Lockee, Trust & Bond, 2020) although, in principle, without specific application for educational purposes, which is why they can be regarded as an example of an interim solution. In a recent UNAM study (Sánchez et al., 2020), Skype is also one of the preferred media for simultaneous work, although this type of task was actually considered to be less important than communication, academic work and storage, in that order. Skype is a tool which has not been greatly exploited by education despite it being a resource with highly functional applications for the teaching-learning process (Mnkandla & Minnar, 2017). It has been brought to the fore by this situation and context.

Authors such as Martínez and Ferraz (2016) or García, Tirado and Hernando (2018) show how Facebook was considered the most popular medium among university students both from a social and educational perspective before lockdown. This study confirms that 83.8% of those consulted actually used this medium for social purposes. However, despite the high percentage, we observed that there was a previous fall in the educational use of online students, with only 7.7%; perhaps it was due to its primary use as a repository for group notes from each module, without further resources, as confirmed by the students' responses. It was also connected to changes in the innovations of the media, as reflected in the work of Puente, Fernández, Sequeiros and López (2015) or due to social movements according to Franklin (2019). However, it should be noted that and there was a statistical difference in the use of this medium between the virtual and classroom-based courses, as reflected in the chart of Figure 1. This is directly related to the age of students from the various types of universities. Virtual universities see the highest concentration of students over 33.3 years old (Gil-Fernández et al., 2019) and, according to the study of Phua, Jin and Kim (2017), it is the age bracket of Facebook users. However, it should be emphasised that students of virtual university courses used the Facebook profiles of their institution not only to look for information about the university, but also to “boost their learning strategies and to promote their social standing” (Gil-Fernández et al., 2019), and this custom seems to have faded. During lockdown, students did not find this medium to be particularly useful for educational purposes, so much so that its use in classroom-based courses remains stable, while it falls in online courses, possibly due to its failure to fulfil the synchronous function that was in such high-demand at that time or due to its lack of usability as it does not operate as a “message board” in view of the lack of academic events.

WhatsApp was the most commonly used medium for social and educational purposes before lockdown. This medium is commonly used for the purpose of quickly distributing teaching materials, such as notes or explanations of problems, among colleagues, as reflected in studies conducted by Suarez (2018) or Fondevila, Marqués, Mir and Polo (2019). It is used for educational purposes as messages are sent and received instantaneously, and are usually short and direct, thereby avoiding the loss of information or ambiguity of long messages (Vilches & Reche, 2019). Before lockdown, this medium was used more by classroom-based students than students of virtual courses, possibly because the latter use alternative forms of media to remain in contact in that environment (Gil-Fernández et al., 2019). During lockdown, its educational use increased only among students of classroom-based courses, while it fell among students of online courses. In respect of the open-ended question, in both types of university, the terms “explanation of problems” and “communication with colleagues” are repeated, which coincides with the previous use, as evidenced by other works which examine this feedback process and how it facilitates academic orientation (Suárez, 2018). These data would be consistent with those obtained at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, where students during lockdown considered communication tools to be more important, irrespective of synchrony, by using WhatsApp, Facebook and even email more intensively (Sánchez et al., 2020).

Before lockdown, YouTube was used by university students in an educational capacity predominantly for the purpose of using resources related to their course, but they neither created their own material nor took maximum advantage of this medium (Yarosh, Bonsignore, McRoberts & Peyton , 2016; Marchetti & Valente, 2018; Moreira, Santana e Santana & Bengoechea, 2019). There were no significant differences in its use at institutional level and this may be due to what has been previously stated: this is a medium that serves as a repository of learning resources and is useful for students from both types of university (Gil-Fernández et al., 2019). Changes are observed not in the educational use, but rather in the intensity, as although it remains the same for classroom-based courses, it increases for online courses, which is explained by the fact that it was already a favoured resource of these students, and they have had more time to use it. However, its benefits for active users, instead of recipients, remain largely untapped.

According to the data obtained, Instagram was the third most commonly used medium before lockdown for educational purposes, and the fourth for social purposes, which therefore supports the study conducted by Peña, Rueda and Pegalajar (2018) wherein it is defined as one of the favourites among university students. This use primarily focused on the use of images as one of the most versatile and user-friendly learning resources (Romero, Campos, & Gómez, 2019). In the same vein as YouTube, it was used more commonly by students of virtual courses than students of classroom-based courses, possibly due to their usual environment and, therefore, the fact that they more accustomed to using these resources. However, during lockdown, the trend has been reversed, since its use by online students fell, while its use by classroom-based students increased, almost as if the latter had finally woken up and started to explore and discover its benefits.

Before lockdown, expressed as a percentage, Pinterest was seventh in the list of social use behind Facebook, Instagram, Skype, WhatsApp, YouTube and Twitter, and second only to WhatsApp in the list of educational use. This predominant educational use may boil down to the fact that it is quite a motivational resource in view of the teaching materials that it makes available (Amer & Amer, 2018). Again, as in the case of Instagram, but more intensively still, its use rises substantially among students of classroom-based courses, who appear to develop a new-found interest in the images and experiences portrayed on this medium, while its use by online students even decreases.

The medium of Twitter (40.6%) was found to be seldom used by students for social purposes during lockdown and less still for educational purposes, such that, as argued by Tur, Marín and Carpenter (2017) and Köseoglu and Köksal (2017), although it is a very interesting and dynamic resource in the exchange of ideas, it remains largely untapped. This is another medium which was not largely favoured during lockdown, either by classroom-based students, even though they are more likely to be in the age group that does use it, or online students. It is possible to consider that its function of advertising events and initiatives was suspended during lockdown.

Before lockdown, SoundCloud and Tumblr were characterised by their minimal use both for social and educational purposes (5.6%) and were used more commonly by virtual university students. These data stand in contrast to the argument defended by Nwosu, Monnery, Reid and Chapman (2017), which suggests that they are more commonly used by classroom-based students, due to the reduced availability of audio-visual materials, which are more characteristic of online courses. In this case, the use by online university students falls and, for classroom-based students, it drops to the point at which it falls into disuse, based on the fact that these users perceive the medium to be recreational and pointless from a work and academic point of view and one that is not needed during the crisis.

On this basis, it is possible to consider that many of the sudden changes in customs brought about by lockdown and related to the use and disuse of certain media, demonstrate the temporary and provisional nature of instructional habits (Hodges, Moore, Lockee, Trust, & Bond, 2020), revealing that students of classroom-based courses seek provisional supports to quickly manage an exceptional situation, but are possibly not driven to consolidate them for the future or motivated by prior reflection. That is why Llorens-Largo and Fernández (2020) takes the view that it is not enough simply to digitise conceptual content, arrange videoconferences or send new materials to students. It is necessary to conceive an innovative and unprecedented instructional design and implement new strategies with a view to finding solutions.

Another noteworthy issue is the stigmatisation of online teaching as opposed to the classroom-based sort, and the consequences that this crisis may have on this factual judgment. Even though it is more tacit than verifiable based on scientific literature, a number of works broach this question directly, such as the recently published work by Hodges, Moore, Lockee, Trust and Bond (2020), wherein they compare the difference between virtual and face-to-face teaching and assert that remote teaching has always been viewed as inferior to the traditional model despite the conclusions reached by scientific literature, and that this challenge may change said perception.

Another risk - which has always existed and has been taken into consideration by the online model - and which is now an “immediate risk” factor in the face-to-face model, in view of its adaptation to the online sphere, is to reproduce excessively declarative and passive patterns, without the participation of the student, by transferring them to long video-conferences and ineffective resources that will cause the student to endure a bad experience (Abreu, 2020). The objective is to make a change, not just to add technologies, but to make profound changes (Barrón, 2020).

Students who study online courses have access to social media which they use for educational purposes as necessary, but they also have access to the particular tools of each institution when they need synchrony in their teaching-learning process. They use these media on a daily basis both before and after lockdown: “contact between students of online university courses is usually made via the particular platform on which the virtual sessions take place, despite the fact that this platform is managed by teaching staff” (Gil-Fernández et al., 2019).

On the other hand, although ICT resources are used in face-to-face teaching, those that operate asynchronously are favoured, which is why the change in the use of media which are characterised by this feature, easy to access and free to use, as in the case of Skype and WhatsApp, is more intensive. We can compare these questions with the fact that the use of social media for academic purposes by online students decreases or remains the same, as we have shown, except in the case of Skype and YouTube to a very minor degree, while the use of almost all media increases among students of classroom-based courses, except for those that may generally be considered to be more recreational and which have not been able to be used as much in recent times, which have declined.

Acknowledgements

This work has been financed by the Project entitled “Evaluation of Digital Teaching Competence in the initial training of teachers in the area of Social Sciences and their Specific Didactics”, carried out within the HDAUNIR (Applied Digital Humanities) research group of the International University of La Rioja.

References

Abreu, J. L. (2020). Tiempos de Coronavirus: La Educación en Línea como Respuesta a la Crisis. Daena: International Journal of Good Conscience, 15(1), 1-15.

Amer, B., & Amer, T. S. (2018). Use of Pinterest to Promote Teacher-Student Relationships in a Higher Education Computer Information Systems Course. Journal of the Academy of Business Education, 19, 132-141.

Barrón, M. C. (2020). La educación en línea. Transiciones y disrupciones. In H. Casanova Cardiel (Ed.), Educación y pandemia: Una visión académica. Instituto de Investigaciones sobre la Universidad y la Educación de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Carneiro, R., Lefrere, P., Steffens, K., & Underwood, J. (2011). Self regulated Learning in Technology Enhanced Learning Environments: A European perspective. Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-654-0

Chamarro, A. (2020). Impacto psicosocial del COVID-19: algunas evidencias, muchas dudas por resolver. Aloma, 38(1), 9-12. https://doi.org/10.51698/aloma.2020.38.1.9-10

Diez-Gutierrez, E., & Gajardo-Espinoza, K. (2020). Educar y Evaluar en Tiempos de Coronavirus: la Situación en España. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 10(2), 102-134. https://doi.org/10.17583/remie.2020.5604

Fondevila, J. F., Marqués, J., Mir, P., & Polo, M. (2019): Usos del WhatsApp en el estudiante universitario español. Pros y contras. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 74, 308-324. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2019-1332

Franklin, T. (2019). The State of Social Media. E-content Magazine, 42(1), 25-27.

García, R., Tirado, R., & Hernando, A. (2018). Redes sociales y estudiantes: motivos de uso y gratificaciones. Evidencias para el aprendizaje. Aula Abierta, 47(3), 291-298. https://doi.org/10.17811/rifie.47.3.2018.291-298

García-Peñalvo, F. J., Corell, A., Abella-García, V., & Grande, M. (2020). Online Assessment in Higher Education in the Time of COVID-19. Education in the Knowledge Society, 21, 12. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.23013

Gil-Fernández, R., Calderón-Garrido, D., León-Gómez, A., & Martin-Piñol, C. (2019). Comparativa del uso educativo de las redes sociales en los grados de Maestro: universidades presenciales y online. Aloma, 37(2), 75-81. https://doi.org/10.51698/aloma.2019.37.2.75-81

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educause Review. https://bit.ly/3lWevob

Köseoğlu, P., & Köksal, M. S. (2017). An Analysis of Prospective Teachers’ Perceptions Concerning the Concept of “Social Media” through Metaphors. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 14(1), 45-52. https://doi.org/10.12973/ejmste/79325

Llorens-Largo, F., & Fernández, A. (2020). Coronavirus, la prueba del algodón de la universidad digital. https://bit.ly/2Rm917X

Maraver, P., Hernando. A., & Aguaded, J. I. (2012). Análisis de las interacciones en foros de discusión a través del Campus Andaluz Virtual, @tic. Revista d'innovació educativa, 9, 116-124.

Marchetti, E., & Valente, A. (2018). Interactivity and multimodality in language learning: the untapped potential of audiobooks. Universal Access in the Information Society, 17(2), 257-274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-017-0549-5

Martínez, M. C., & Ferraz, E. (2016). Uso de las redes sociales por los alumnos universitarios de educación: un estudio de caso de la península ibérica. Tendencias Pedagógicas, 28, 33-44. https://doi.org/10.15366/tp2016.28.003

Mnkandla, E., & Minnaar, A. (2017). The Use of Social Media in E-Learning: A Metasynthesis. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5), 227-248. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3014

Moreira, J. A., Santana e Santana, C. L., & González, A. (2019). Ensinar e aprender nas Redes Sociais Digitais: o caso da Mathgurl no YouTube. Revista de Comunicación de la SCEEI, 50, 107-127. https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2019.50.107-127

Nwosu, A. C., Monnery, D., Reid, V. L., & Chapman, L. (2017). Use of podcast technology to facilitate education, communication and dissemination in palliative care: the development of the AmiPal podcast. BMJ supportive & palliative care, 7(2), 212-217. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001140

Peña, M. A., Rueda, E., & Pegalajar, M. C. (2018). Posibilidades didácticas de las Rede Sociales en el desarrollo de competencias de educación superior: percepciones del alumnado. Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación, 53, 239-252. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2018.i53.16

Phua, J., Jin, S. V., & Kim, J. J. (2017). Gratifications of using Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or Snapchat to follow brands: The moderating effect of social comparison, trust, tie strength, and network homophily on brand identification, brand engagement, brand commitment, and membership intention. Telematics and Informatics, 34(1), 412-424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.06.004

Puente, H., Fernández, M., Sequeiros, S., & López, M. (2015). Los estudios sobre jóvenes y TICs en España. Los estudios sobre la juventud en España: Pasado, presente, futuro, 110, 155-172.

Rogers, H., & Sabarwal, S. (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic: Shocks to Education and Policy Responses. The World Bank. https://bit.ly/3fiqWsY

Romero, J. M., Campos, N., & Gómez, G. (2019). Follow me y dame like: Hábitos de uso de Instagram de los futuros maestros. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 94(33.1), 83-96. https://doi.org/10.47553/rifop.v33i1.72046

Sánchez-Mendiola, M., Martínez-Hernández, A. M., Torres-Carrasco, R., de Agüero Servín, M., Hernández-Romo, A. K., Benavides-Lara, M. A., Rendón- Cazales, V. J., & Jaimes-Vergara, C. A. (2020). Retos educativos durante la pandemia de covid-19: una encuesta a profesores de la UNAM. Revista Digital Universitaria, 21(3). https://doi.org/10.22201/codeic.16076079e.2020.v21n3.a12

Somerville, J. A. (2008). Effective Use of the Delphi Process in Research: Its Characteristics, Strengths and Limitations. Corvallis. https://n9.cl/0yze

Suárez, B. (2018). Whatsapp: su uso educativo, ventajas y desventajas. Revista de Investigación en Educación, 16(2), 121-135.

Tur, G., Marín, V., & Carpenter, J. (2017). Uso de Twitter en Educación Superior en España y Estados Unidos. Comunicar, 5(XXV), 19-28. https://doi.org/10.3916/C51-2017-02

Vilches-Vilela, M. J., & Reche-Urbano, E. (2019). Limitaciones de WhatsApp para la realización de actividades colaborativas en la universidad. RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 22(2), 57-77. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.22.2.23741

Yarosh, S., Bonsignore, E., McRoberts, S., & Peyton, T. (2016). YouthTube: Youth video authorship on YouTube and Vine. In CSCW '16: Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (pp. 1423-1437). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2818048.2819961